Browsing the 1641 depositions

An examination of an online primary source on the 1641 rebellion. By John Dorney

The 1641 rebellion was a Catholic uprising that broke out on October 23, 1641. While initially intended, by a small group of Ulster gentry who undertook it, to be a swift seizure of power in Dublin in the name of the King, followed by the imposition of Catholic demands, it sparked off a brutal eleven year war.

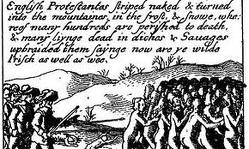

The rising, which was marked by the massacre of Protestant English and Scottish settlers, left a long lasting scar in Irish Protestant memory. They believed it had been an attempt by the Catholics to wipe out their community, a plot only thwarted by divine providence.

The Depositions are a collection of Protestant victim accounts of the 1641 rebellion and are housed in Trinity College Dublin

Protestant experiences of the rebellion were recorded in Depositions, sworn statements taken in 1642 and again in the 1650s, with a view to compensating Protestants who had been robbed or displaced and, second, to establish Catholic guilt and therefore identify culprits to punish once the rebellion had been put down. Today these statements are housed at Trinity College Dublin, here.

Back in 2010, the 1641 Depositions, which were digitised in a vast process over several years, went online as the Irish Story reported at the time. They can be browsed for every county in Ireland here and are an unparalleled, though, as we will see, a partial, window into the great convulsions in mid seventeenth century Ireland.

In recent years, a great many primary sources from the twentieth century Irish revolutionary period have gone online, from the Bureau of Military History to the Military Service Pensions collection. The breadth and ease of use of these collections have made them of great use to all scholars and enthusiasts of that period.

Less widespread use however has been made of the digital Depositions, which is unfortunate, as it provides a possibly even more valuable insight into a much more remote past. So, as an experiment rather than a deep dive into the Depositions, this piece is the result of a morning spent browsing the depositions more or less at random to see what I could find.

Henry Jones and establishing a narrative

Opening the depositions in County Dublin, one of the first is that of Henry Jones, taken in Dublin in 1642. Jones was a Protestant Archbishop, one of the main architects of the Depositions project. He seems to have been a position of authority in Limerick at the outbreak of rebellion.

He testifies that the rebellion was planned by priests ‘brought in from foreign parts’ under the protection of exiled Earl of Tyrone – son of Hugh O’Neill, leader of the native Irish resistance in the Nine Years War.

Jones goes on to say that he arrested a priest who stated, ‘That within 3 years there should not be a protestant in Ireland, or words to that purpose, with some other material Circumstances which I do not now remember’. The Priest was imprisoned in Dublin Castle.

Jones further testifies that another ‘papist priest (newly arrived out of Flanders’) after his arrest at Naas, told of an ‘intercourse of letters between the Earl of Tyrone with others in Flanders, and the Popish [Catholic] Primate of Armagh, Reilly, concerning an invasion within a short time’.

This merits some comment. It is interesting in that it shows what Protestants and the English state in Ireland thought had happened in October 1641. But it also shows how unreliable a source the deposition can be.

Certainly Irish Catholic exiles were prominent in the Spanish Army of Flanders (fighting the Dutch in the Eighty Years War in what was then the Spanish Netherlands), and were also in close touch with Irish Catholic clergy on the continent. However, the exiled Earl of Tyrone (John, son of Hugh O’Neill) had nothing to do with the rebellion. In fact he had been killed fighting in Spanish service, attempting to put down a revolt in Catalonia in January 1641.

Nor was the rebellion fomented by an influx of priests nor coordinated by the Catholic hierarchy. Rather it was the work of a small group of mostly Ulster Catholic gentry led by Phelim O’Neill.

Henry Jones’ deposition establishes the Protestant narrative of the 1641 rebellion as an international Catholic conspiracy

However, this does not mean that Jones’ testimony is without merit. He also reports on rumours among the Catholics of Munster, ‘That in the Parliament of England, the cutting off of all the papists in Ireland, of what degree soever, was concluded upon… The execution of that Resolution being committed to the Council in Ireland’.

This gives us an idea of the atmosphere on both sides leading up to the outbreak of the rebellion. Both Catholics and Protestants believed that a plot was afoot to massacre them. Paranoia and fear were starting to reach boiling point by October 1641 and could, in their consequences, be as lethal as pikes or muskets.

Jones is also interesting on the rebels’ demands which included, according to him ‘loyalty to his majesty’ (Charles I) but government of Ireland by two Lords Justice ‘one of the ancient Irish race [i.e. Gaelic Irish] the other of the ancient British inhabitants of the Kingdom [‘Old English’], provided that they be of the Romish [Catholic] profession’.

They were to demand, Jones tells us, a Catholic dominated parliament and repeal of Poynings law, which made the Irish Parliament subject to the English one. ‘All acts prejudicial to the Romish Religion shall be abolished’. The Plantations, or mass seizures of native owned land, were to be reversed and ‘the ancient proprietors to be reinvested’.

This is in fact not too far off the actual demands of the insurgents when they became organised later that year in the Catholic Confederation based in Kilkenny.

And finally, Jones tells us, the rebels planned to impose Catholicism on England and Scotland and further afield. ‘That this kingdom being settled, there are 30,000 men to be sent into England, to join with the French and Spanish forces, and then Jointly to fall upon Scotland, for reducing both Kingdoms to the obedience of the Pope’.

They would then aid the Spanish in putting down the Protestant Dutch Republic which had rebelled against Spanish authority in the 1580s, ‘Which being finished, they have engaged themselves to the King of Spain for assisting him against the Hollanders’.

Jones had a definite political agenda, which was to present to the English Parliament an account of the ‘lamentable condition’ of Irish Protestants in 1642 and to urge that Parliament to re-conquer the country. Thus, the more threatening he could make the Irish Catholics’ agenda appear to English and international Protestantism, the better it suited his agenda.

Far from being a ground level report of a victim, which many depositions are, Jones’ statement is basically a political tract, a advancing a certain interpretation of the rebellion as an international Catholic conspiracy.

Ground level accounts

Sifting through the online depositions, it is easy to find a more ground level deposition.

One such account, totally different from that of Henry Jones, is that of Davie Williams of Kilmore parish Armagh, near Portadown. This is a straightforward list of property lost at the hands of the rebels. He also names the perpetrators, which indicates they were known to him before the rebellion

He testified that ‘about the last of October [1641] he was robbed and despoiled of goods & chattels to the value of the particulars undermentioned [goes on to list cows, corn, clothes, foodstuffs, horses and oxen.] He goes on to name the perpetrators.

‘The Rebels that robbed this deponent were Mr Patrick O Quigge, Turlough Quigge, Patrick O’Flynn, Art McKane [all of the parish of Loughgall] They ‘stripped this deponent & his wife whom they kept two nights & a day in stocks after this deponent her husband was gone from her’.

Many ground level accounts held in the depositions make harrowing reading.

That Williams could name the men who robbed him and assaulted his wife is telling. Very likely they had lived sided by side before the rebellion, possibly on lands confiscated from the O Quigges,O’Flynns and McKanes. While Williams may well have thought that they lived, as many Protestant accounts of the rebellion would assert, ‘in perfect harmony’, the native Catholics may well have spent years secretly nursing their grudges against the ‘planters’.

While not lethal, their revenge, on Williams’ account and keeping in mind that the depositions are a biased source, was savage. They stripped Williams and his wife naked, took his wife away and kept her in stocks for two days, which very strongly hints at some sort of sexual assault. Williams was illiterate (a reminder that many Protestant settlers were not great landowners, but simple farmers and artisans) and made his mark on the deposition in place of a signature.

Another such case is that of Elizabeth Tunsted of Clare. She was ‘wife to Thomas Tunsted, County of Clare clerk (who was, it is noted, ‘a British Protestant’). She deposed on behalf of her husband who was ‘laying very sick’.

She stated ‘That on or about Christmas last [1641] & since the beginning of this present rebellion in Ireland he lost was robbed & forcibly despoiled of his goods and Chattels worth 267 li.’

The Tunstells were robbed of sheep, cattle, corn, cash and a gun. She suggests that they were people who owed them money. ‘but by means of this rebellion this deponent cannot get satisfaction from them’.

There are no suggestions of violence here, which backs up the suggestion of many modern historians that lethal violence occurred only as the rebellion dragged on and a cycle of revenge and retaliation developed, especially in Ulster.

One such victim of lethal violence was the family of Anne Bullinbrooke, ‘late of Dungannon in the County of Tyrone widow of John Bullinbrooke, Master of the free school of the County’.

She deposed that she and her husband were ‘forcibly robbed and turned out of all their goods, chattels and estates’ by (here, ‘the rebels’ is crossed out and replaced with ‘Sir Phelim O’Neill’, the initial leader of the rebellion) ‘and his ungodly and rebellious followers’.

She states that having been ‘stripped naked and left comfortless to the open air… in the wild woods where they did live miserably … her husband and one child at length died through hunger and cold’.

She testifies that the local rebels including Randal McDonnell and others ‘whose names she knows not’, murdered ‘Mr Mather, the minister of Dunnamore and Mr Blith, minister of Dungannon, William Odber, another minister and about twelve more English Protestants in or near Dungannon’.

Bulinbroke reported that it was the rebels’ objective that, ‘they would leave neither Scottish nor English in Ireland And when that was done the King of Spain should be their King’. She also reports, however, that some rebels thought they had the sanction of King Charles for their rebellion and that if they had not risen in arms, ‘the Scots would have shortly risen up against them and either would have enforced them to go to the Church [i.e. conform to Protestantism] or or would have killed them all’; an indication, perhaps of the range of conflicting motives behind the rebellion at its outset.

In all it is thought that between 4-12,000 Protestant settlers were killed in the initial months of the rebellion, either directly or through privation and disease, having been expelled from their homes.

The Depositions are not by definition, easy reading. But they are magnificent digital resource, with material from every part of Ireland. This is only a small fragment of the material they contain and a readers who browse the depositions from their local area will undoubtedly find much of interest.

See also a podcast discussion between John Dorney and Cathal Brennan on the 1641 rebellion on the Irish History Show.