Scrapping: The Early Years – Dublin Boxing in the late 18th and early 19th centuries

By Ray Esten

In memory of Darren Sutherland, a life too short

Rebirth

We often assume that modern boxing has its origins in the Ancient world. It is believed that Rome abolished the practice in AD 383 on account of its alleged brutality.

This apparently brought a lull until it re-emerged in seventeenth century England. In this period the prize-fight found favour amongst a certain number of the aristocracy.

The King himself, George I (1714-1727) ordered the erection of a small enclosure in Hyde Park for that purpose. Furthermore, Jack Broughton (protégé of the first champion of England James Figg (1719-1730) enjoyed the patronage of the Duke of Cumberland (third son of George II).

A very different game

Prize-fighting was a crude endeavour, fought with bare fists, few rules and devoid of referees. However, Broughton’s rule book (published in 1743) created change. It comprised of seven rules which asserted that … ‘if a second does not bring his man to the side of the square within the space of half a minute he shall be deemed a beaten man.’[1] It also forbids grabbing below the waste and the hitting of a man when he was down. [2]

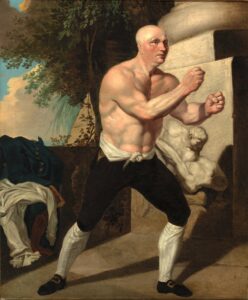

Jack Broughton’s rule book of 1743 helped to revive organised boxing, but it was very different from the sport we know today.

Broughton’s rules certainly put the sport on a good footing. Yet crude elements remained, for instance, ‘a round only ending when a man went down.’ However, it would be an error to dismiss it as wholly barbaric. There was a number of skilled practitioners who employed techniques that had elements of modern-day Mixed Martial Arts.

For instance, Broughton’s technique was to get his opponent in an ‘’artificial lock’’, depriving him of all power of resisting and falling.[3] In fact, wresting was a critical component and the move known as ‘’cross buttocks’’ (similar to the present-day hip-toss throw) could easily swing a fight towards the skilled practitioner. Anyone who has practiced Brazilian Jiu jitsu of No Gi wresting will understand the amount of skill, timing and risk involved.

Continuity and change

Prize fighting looked to be on a strong footing in mid-eighteenth-century England however, the shock defeat of Broughton, resulted in the withdrawal of royal favour. It has been said that the Duke of Cumberland had betted heavily on Broughton’s win.

The banning of the organised boxing arena, therefore, arose not, it seems, out of moral offence or social outrage, but because one of its prominent patrons lost heavily from a bet gone wrong.[4]

Whatever the truth of this, boxing was illegal from 1750. Its supporters ‘the fancy’ could either refrain from this form of sport or band together in support of alternative and even illicit social strategies and practices.[5]

The Dublin fight scene

The Dublin fancy also submitted to the lure of a good fight and the lay of a wager. However, the Dublin scene stood in contrast to that in Britain, as it was largely comprised of the artisan class, a number of whom were attached to the city’s warring gangs, the ‘’Liberty boys’’, (tailors and weavers) and the ‘’Ormond boys’’ (butchers) from the market, whose faction fights on Dublin’s streets were notoriously bloody.[6]

The extent in which their pugilistic endeavours turned foe into friend or averted such feuds is open to interpretation, but the two factions certainly continued to clash. These feuds caused varying degrees of mayhem and a few deaths too. Therefore, it was highly unlikely that their involvement in pugilism (be it directly or indirectly) encouraged potential benefactors.

Prizefighting in Dublin was closely associated with the city’s warring street gangs, the Ormonde Boys and Liberty Boys.

Irish pugilists could never envisage the kind of prestige achieved by their English counterparts. In fact, their experience contrasted starkly. They lacked patronage just as they lacked social acceptance. Therefore, the bouts remained underfunded and unorganised, the purse small and the attendance the same.

The date in which they employed Broughton’s rules is debatable. Yet, they may well have come to some kind of alternative arrangement before raising their fists. The fights typically happened outdoors, far away from prying eyes. The locations included Arbour Hill, Kilmainham, Georges Quay, Lazars Hill (Townsend St) or the ground adjacent Long Lane and St. Marks Churchyard (Pearse St). [7]

The fighting fields of St. Marks

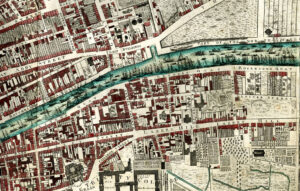

Fights sometimes took place at the eastern edge of the city along the south docks.

Rocque’s Exact survey of the city and suburbs of Dublin 1756, adjoining shows Georges Quay and Sir John Rogerson’s Quay to be lined with the masts of ships.[8]

Close to the main thoroughfare at Lazars Hill and behind Georges Quay was the church of St Marks (Pearse St). Such was the maritime history the church pulpit is believed to have been made from the poop of a ship that sank in Dublin bay.[9]

Fights often took place in the fields behind George’s Quay on the south docks.

The adjacent fields that lay close to the town’s end attracted fistic events. The church was officially consecrated in 1757 and therefore dedicated to a higher purpose. Yet, this did little to divert those who partook, watched or betted on prize-fights.

The Royal Navy Press gangs (often with parliamentary consent) roamed the streets in search of able-bodies and the taverns, country lanes, and the fields of St Marks became a hunting ground, especially whenever a football match or a boxing or wrestling bout attracted a crowd. Yet, the press gang was also resisted by force when they came upon a Dublin crowd, some being willing to drive them to the water’s edge with stones, returning pistol shot for musket shot. [10]

Further a field

Those bold enough to disregard the naval uniform might well have tried their hand at prize fighting,

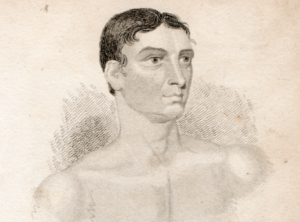

While it remained a niche sport in Ireland , those with handy fists could avail of opportunities across the water. England, the cradle of pugilistic activity, had a strong Irish contingent. Thus, it was just a matter of time before an Irishman had contested their title. The first of these was Galway born Peter Corcoran. He had commenced business in London as coalheaver but, he was pressed into the Navy and taken to sea. It was on return that he became a pugilist.

He won the championship by knocking out Bill Darts at Epsom races in 1771 (reign as champion 1771-5).[11] This afforded him legendary status in Ireland.[12] A challenger to all comers at St Marks Church in 1787 declared that he was ‘the first pupil ever the celebrated Corcoran had taught’.[13]

Waning popularity and revival

A contest between the English fighter Daniel Mendoza and the Irishman Squire Fitzgerald in 1791 (Daly Club Dame Street) may have received backing from non-other than the Duke of Leinster and the Squire might have been a distant kinsman of the duke.[14]

Galway born Peter Corcoran was pressed into the Navy and returned to Ireland to become a pugilist

The celebrated Mendoza’s presence in the city did cause excitement amongst certain circles. However, the fight with Squire Fitzgerald was a minor affair. It did not compare to the 60,000 who gathered to see the Humphries/Mendoza fight at Hampshire.[15] Nevertheless, some five thousand spectators did gather on St. Mark’s fields in 1792 to witness a much-anticipated bout between a slater and a weaver. [16]

The sport seemed to be ascendant in 1790s, but it had all but vanished by the end of the decade, in part perhaps because of the political upheaval of that decade, culminated in the Rebellion of 1798. During the 1790s the ‘seditious vicinity’ of Poolbeg Street was searched and concerned loyalists instituted vigilante patrols in the parish of St Marks[17], which may have discouraged pugilistic activity in this area. James Kelly has noted in his excellent study of Sport in Ireland 1600-1840, however, that the pugilist’s impulse faded but did not die during the decade following the 1790s and early years of the nineteenth century.

The fighters

By the time of the Act of Union in 1800, a Dublin fighter named Paddy Gamble had achieved a formidable reputation. It was said that his …’frequent skirmishes in the Liberty, and his exhibitions in the Phoenix Park, rendered him a bruiser of notoriety.’

The chronicler Pearse Egan said that he had a most tremendous fist, and dealt out punishment with uncommon severity.[18] He was one of the new generations of Irish pugilists or fighters possessed of Irish ancestry, who reanimated in the sport in England.[19]

An often-overlooked star of the prize ring was Dan Dogherty. After having a good fighting career at home, he packed up for England. His first engagement in 1807 he defeated Dick Hall. In February 1808 and May of 1810, he defeated George Cribb (brother of Tom Cribb). Marking him as one of the best men of his time.

Irishman Dan Dogherty fought celebrated English fighter Tom Belcher in several bouts

At Epson downs he fought Tom Belcher (brother of James Belcher). This was a substantial event and Belchers advisors on that occasion included Mendoza and Carter and Dogherty was assisted by Copley and Dick Hall.[20] Furthermore, Lord Byron noted that …’I had backed (Dogherty) and made the match for him against Belcher.’[21]

Dogherty faced Belcher again at the Curragh Kildare (his home county). A confident Dogherty showed himself wrapped in a box coat of no trifling dimensions and instantly gave the castor a toss in the air, loudly vociferating ‘’Ireland for ever’’[22] While Dogherty put on a stout-hearted display he was ultimately defeated. The Marquis of Sligo immediately subscribed five guineas for the beaten man, as did all other gentlemen more or less. The collection amounted to 70 or 80I; an indication of the raised status of prize fighters in the early nineteenth century.[23]

The spot at the Curragh in which Dogherty had been defeated was renamed after the victor. However, ‘Belchers Hallow’ would soon be immortalized by another name. Irish champion Dan Donnelly was perhaps the most celebrated Irish prize fighter of his time. He may have commenced boxing at St Marks fields – it was but a stone throw from his family home. He might even have been, a docker and his earliest fame as a boxer gained among the coalmen of the ‘’Kays’’[24]

He thought about fighting before he could talk

And instead of a go-cart, he first learned to walk

With a sprig of shillelagh and shamrock so green.

George’s Quay was his school, the right place for breeding

Where the boys mind their stops if they don’t mind their reading

Just one of a number of street ballads and poems that immortalized the name of Dan Donnelly.

Donnelly fought a number of Englishmen including Tom Hall (Curragh 1814), George Cooper (Curragh 1815) and Sam Oliver (Sussex England 1819). The latter created great excitement on both sides of the water. The Hall fight alone attracted between forty and fifty thousand spectators.[25] An astonishing amount when contrasted with the twenty-thousand that turned out to see Tommy Burns v. Jack Johnson or the Jack Dempsey v. Jess Willard fight some hundred years later.

Conclusion with overview of the sports development

Prize fighting in England was non plus ultra by the mid-eighteenth century. Broughton’s rule book, though rudimentary, was a giant step towards making it a viable sport.

Though Broughton’s surprise loss in the prize ring bought the withdrawal of royal favour, prize fighting was not snuffed out completely. It appealed to a section of society which included the Irish diaspora of which Peter Corcoran was the first champion (reign 1771-5).

In Ireland it lingered on the fringes of society. It was mostly endorsed by the artisan class and its association with the city warring factions did little to aid its reputation. Nonetheless, it reached a highpoint in the early nineteenth century, the days of Dogherty and more so Donnelly. On the latter’s death in 1820 Donnybrook Fair (Donnelly had exhibited there) erected a booth[26]were sparring was facilitated every day during the fair.[27] Donnelly’s death was without question a loss to the Irish scene. Yet, it also coincided with the fall from fashion of prize fighting in England.

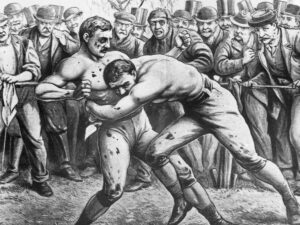

Boxing lingered on the fringes of society until the late nineteenth century.

Fixed fights and prolonged bouts had done much to cast a shadow over its longevity. The contest between Deaf Burke and the Irish champion Simon Byrne (staged England 1833) only served to emphasise this.The bout lasted over 3 hours and was noted as particularly brutal. The Times reported that Byrne was put to bed in a stupor. The punishment on the left side of his face severe.[28]

‘Brave Simon Byrne, that hero bold, alas! He is no more’

Byrne’s death was partially responsible for the introduction of London Prize Rules (1838).[29] Yet, the early years of the Victorian period witnessed a sharp decline in popularity. The ‘Great Hunger’ (1845-49) unwittingly equipped the United States, which had replaced England as the cradle of prize fighting, with great battlers like Owney Geoghegan. Closely followed by Irish immigrants like Yankee Sullivan and Paddy Ryan who were succeeded by the Irish-American superstar John L. Sullivan.[30]

Though Queensbury Rules were published in 1867[31] it was not until the 1880s that they were fully adopted and a real effort was made to standardise, for instance, weight divisions.[32] Boxing under these rules returned to the old site at St. Mark’s church in 1890. However, this time the contests were held indoors, inside the walls of the Antient Concert Rooms (Pearse Street). While it was no Madison Square Garden, it was the home of Irish boxing for a number of years.

Boxing not only survived as a spectator sport, it thrived. Why? Because it adapted. Though it was not an easy evolution by any means it was aided by a kind of magic that only sport can claim, a potent mix of adrenalin, comradery, rivalry and of course the allure of a wager. The golden period was certainly the twentieth century.

Today its profile is strong. Multiple World Champion Katie Taylor is part of that lineage. She worships at the church of St Mark. Not far from the old sod.

References

[1] Advisers consisted of a Second- the person who backs another in fighting, and sees that he is not dealt unfairly. The Bottle-holder -an assistant to the second, so termed from holding a water bottle on the stage, for the use of the person fighting.

[2] Fistiana; or, The Oracle of the Ring (London, 1841) p. 29.

[3] W. Buchanan-Taylor and James Butler What do you know about Boxing? (London 1947) p. 199.

[4] Denis Brailsford Morals and Maulers: The Ethics of Early Pugilism Journal of Sport History Vol. 12, No. 2 (Summer 1985) p. 133.

[5] Scott J. Juengel Bare-Knuckle Boxing and the Pedagogy of National Manhood Studies in Popular Culture Vol. 25, No. 3 (April 2003) p. 96.

[6] James Kelly Sport in Ireland (Dublin 2014) pp. 284-7.

[7]James Kelly Sport in Ireland 1600-1840 (Dublin 2014) pp. 283-90.

[8] City Quay is absence from Rochue’s map as it dates from 1766 as is Great Brunswick Street (Pearse Street) the main thoroughfare was Lazars Hill (Townsend Street).

[9] Adreian MacLoughlin Guide to Historic Dublin (Dublin 1979) p. 38.

[10] Joseph W. Hammond Georges Quay and Rogerson’s Quay in the Eighteenth-Century Dublin Historical Record Vol. v No. 2 December, 1942 February, 1943 pp. 47-8.

[11] Ed James, The Lives and Battles of the Champions of England from 1700 to the present time (New York 1879) p. 8.

[12] It has been alleged that Corcoran throw the fight in exchange for money. The only evidence for this is the short duration of the bout (1 round). Fight fixing did much to disgrace the sport.

[13] James Kelly Sport in Ireland 1600-1840 (Dublin 2014) p. 297.

[14] Wynn Wheldon The Fighting Jew: The life and times of Daniel Mendoza, Champion Boxer (London2019) pp. 60-69.

[15] Maurice Golesworthy The Encyclopaedia of Boxing (London 1960) p. 20.

[16] James Kelly Sport in Ireland 1600-1840 (Dublin 2014) p. 299.

[17] Ruan O’Donnell Robert Emmet and the Rebellion of 1798 (Dublin 2003) pp. 61-2.

[18] P. Egan Boxiana or, sketches of antient and modern pugilism, from the days of the renowned Broughton and Slack to the championship of Cribb. Vol. 1 (London, 1823) p. 239.

[19]James Kelly Sport in Ireland 1600-1840 (Dublin 2014) p. 306.

[20] New York Clipper, 19 January 1884.

[21] Letters Journals of Lord Byron with Notices of his life by Thomas Moore Vol. 1 (London 1830) p. 129.

[22] The Sportsman’s Magazine of Life in London (Miles Boy ed) Volume 1. (London 1845) p. 270.

[23] The Sporting Magazine (London 1813) p. 63.

[24] John McCormick (‘’Macon’’) The Square Circle or stories of the prize (New York 1897) p. 14.

[25] The Fancy; or True Sportsman’s Guide Vol. 1. (London, 1826) p. 372.

[26] Donnybrook Fair ran for eight days in the month of August

[27] Freemans Journal Monday, August 28, 1820.

[28] The Times Tuesday 4, 1833.

[29] Tom Sawyer Noble Art an artistic and literary celebration of the Old English Prize Ring (London 1989) p. 23.

[30] The Champions of the American Prize Ring compiled by William E. Harding (New York 1881) pp. 1-18.

[31] Under Queensbury Rues contests were fought with gloves, for a specific number of rounds. Wresting was forbidden and after a knockdown a fighter was given 10 seconds to stand or be deemed beaten.

[32] Maurice Golesworthy The Encyclopaedia of Boxing (London 1960) p. 207.