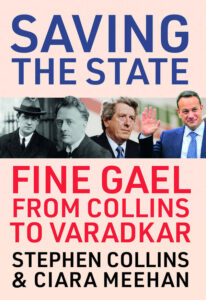

Book Review: Saving the State: Fine Gael from Collins to Varadkar

By Stephen Collins and Ciara Meehan

By Stephen Collins and Ciara Meehan

Published by: Gill Books (2020)

Reviewer: Barry Sheppard

We have all come to realise that, despite its usefulness the unforgiving public arena that is Twitter provides very little room for reasoned debate. A raft of accounts on the platform apparently exist solely to confront on any subject of their choosing, revelling in the act.

Such was the case when news of ‘Saving the State’ was announced on the platform by one of the book’s co-authors a few weeks ago. A deluge quickly emerged with people who had somehow read and formed an opinion on a book which had yet to be released eager to give the author their damning verdict. Such is Twitter.

There is, however, the matter of the book’s title which needs addressed outright (and which drew the first criticisms online). The phrasing of the title was bound to generate a certain amount of heat. No doubt the co-authors were prepared for this to become the focus of attention. At first glance one could perhaps be forgiven for interpreting the title as one which accompanies a history officially endorsed by the party.

This book traces the ancestry of the Fine Gael party (founded 1933) back to Michael Collins and the pro-Treaty faction of 1922

Indeed, the word ‘hagiography’ has been uttered (on Twitter, of course). The book is certainly not that. The title is reflective of the deeply held views of party leaders throughout the decades, who genuinely believed that they stood between society and anarchy. This is demonstrated throughout the book, from W.T. Cosgrave, his son Liam, and Garret Fitzgerald. Whether or not the authors share this belief is up to the reader to decide.

The inclusion of the long clambered-over body of Michael Collins, which forms part of the subtitle ‘From Collins to Varadkar’, has also been a source of puzzlement for some observers. Numerous Twitter responders believed they were being helpful in pointing out that Collins was never in Fine Gael, or even their predecessor Cumann na nGaedheal. This is, of course something of which the authors are well aware, and address early on. More of that shortly.

The joint nature of the publication, with the two authors coming from seemingly different walks of life has been a further point of interest. Stephen Collins, a veteran political journalist in the Irish Times, Irish Press, Sunday Press among others has a high public profile, and is known for the odd polarising take on contemporary political matters. This has led some to question if this approach can work with the more academic training of his co-author. However, this is first and foremost a political book and is on terrain in which Collins has a lifetime of experience.

The second author, Dr Ciara Meehan has, perhaps like most academics, a lower public profile than a seasoned political news correspondent. Meehan’s work, however, especially that which tackles Fine Gael, speaks for itself. The author of a number of publications including The Cosgrave Party: A History of Cumann na nGaedheal, 1923-1933 (2010), and A Just Society for Ireland? 1964-1987 (2013) are very good studies and have been well-received by readers.

Arguably, there are not many academics at the present time in a better position to tackle the history of the Fine Gael party. Nevertheless, in an era where historians are assessed not only on their academic abilities, but also on what is termed ‘impact’, a joint endeavour such as this book will most likely reach that sought-after wider audience.

The introduction tackles that Collins issue (Michael, not Stephen) head on, with the authors pointing out that his demise before either party was formed matters little to the Fine Gael faithful. It is argued that most party members tend to accept without question that had he lived, Collins would have become a Fine Gael member.

Indeed, Meehan has shown this connection before in her 2008 article ‘Fine Gael’s Uncomfortable History: The Legacy of Cumann na nGaedheal’,[1] which provides great insight into the views of party members on the Collins issue.

Collins’ symbolic worth, of course outweighs any practical political impact he may have had in either guise of the party. Like any institution with national ambitions, a solid foundation myth is needed, and Collins fulfils this role. Of course, this is by no means a unique scenario, and is prevalent in politics worldwide.

Collins inclusion in Fine Gael lore is reminiscent of Brunk and Fallaw’s views on political icons in post-colonial South American countries. They state: ‘Both in life and as the sacred, charismatic dead, heroes serve as a kind of cultural glue that helps hold together many kinds of communities’.[2] This is certainly the case with Collins, a man who never wore the colours of Fine Gael, but one who acted as the glue which, at times helped to solidify the legacy of the party.

The authors thankfully resist any temptation to delve into counterfactuals when considering Collins as a leader of Fine Gael. His authoritarian streak is rightfully mentioned, however (something which is often glossed over, with a few notable exceptions).[3] The introduction also sets out the need to address the ‘problematic reality’ of Fine Gael’s 1933 founding, specifically the elements which made up the new whole.

Naturally, this means the officially airbrushed Eoin O’Duffy. Truthfully, there could be no other credible way to tackle the history of this party without addressing it. Just as the Twitterati pointed to Collins inclusion on the book’s cover, they were also quick off the mark to highlight O’Duffy’s omission. They will perhaps be contented to know that O’Duffy (in Blueshirt uniform) adorns the spine of the book.

The Cosgrave Party

Naturally, W. T. Cosgrave is the focus of the first chapter, one of the links between the revolution, Collins, and the more established years of the party. This is territory Meehan knows well and has explored in her first book The Cosgrave Party.

Faced with considerable tasks of attempting to stabilise the new state at a time of civil war, Cosgrave is unambiguously portrayed as the leader of a party who stood for law and order. Indeed, ‘law and order’ is a theme emphasised throughout the chapter and beyond.

The Irish Civil War, almost 100 years on still casts a shadow, and one feels that the book pronounces many judgements on the republican campaign in that brief conflict. Descriptions the ‘notorious reprisal’ of Ballyseedy on the Free State side are relayed.

However, one of the most questionable incidents of the period is only briefly referenced, the kidnap and murder of Noel Lemass. The Lemass murder is referenced in a single line, despite its brutality and its impact upon those in power. Indeed, according to Seán Kennedy, the murder was a ‘serious enough blow to Cumann na nGaedheal’s self-image as the law and order party’.[4]

Cumman na nGaedheal viewed themselves as having save the stated in the Civil War period and its aftermath.

Some interesting and less well-known points are made about the early years of the Cosgrave party. Points regarding the changing nature of Cumann na nGaedheal over the early years of the state are well made, showing that within itself the party was something of a broad church, a fact which is not popularly appreciated. A further interesting point on the perception of Cumann na nGaedheal as tied to the upper-class is addressed via commentary on party member’s official attire.

This is especially of interest if one considers that in February during the 2020 election, Leo Varadkar claimed that class had never been an issue in Irish politics. One only needs to glance at the cartoons of Victor Brown in the Irish Press in the early 1930s to see that class was certainly an issue, with Cosgrave and his top hat and tails symbolising the gulf between Cumann na nGaedheal and what is termed the ‘real’ Irish person.

Outside of law and order, other political issues of the state’s early years are addressed, including the payment of land annuities to Britain. This issue came to the fore with the rise of Fianna Fáil, and the authors argue that their stance ‘represented a combination of nationalist rhetoric and economic self-interest’.

However, another important element is not addressed, which Campbell and Varley examine in Land Questions in Modern Ireland. They argue that the economic nationalism of self-sufficiency ‘acquired further legitimacy by being consistent with Catholic social teaching, as enunciated in the papal encyclicals Rerum Novarum and Quadragesimo Anno’.[5]

A similar point is also raised by Michael McDowell, who argues that Quadragesimo Anno ‘transformed Irish social and economic debate’ by seemingly ending ‘the free trade orthodoxy which characterized the Cosgrave government’.[6] These factors are important and often overlooked as Catholic social teaching would become a major force in the Free State during the 1930s, and one which Fianna Fáil grasped as politically expedient.

The 1932 Irish election, coming so soon after Cumann na nGaedheal’s 1931 Public Safety Act is rightly noted as hugely important, and allows analysis of the election to be framed in terms of the safety and stability of the state. Indeed, the authors have focused on the IRA factor of the election, stating that Fianna Fail and the IRA ‘were hand in glove’. Furthermore, they highlight what they call Cosgrave’s increasingly negative election tactics, the ‘red scare’ which was thrown at Fianna Fáil with gusto.

These are surely important elements in the election. However, the very pressing social needs of the electorate, such as adequate housing are not discussed. The importance of these issues has generally been relegated when it comes to the historiography of this election. Nevertheless, they were addressed by contemporary newspapers, notably the Irish Times,[7] an outlet not known for its love of de Valera’s brand of self-sufficient nationalism. Indeed, housing crops up in future elections which the book covers, including the most recent election of 2020 where housing and health dominated concerns.[8]

O’Duffy

Chapter Two largely dedicates itself to the reintegration of O’Duffy into the party history. This was always going to be one of the more important and interesting aspects of such a study, and as the authors note in Fine Gael circles any mention of the party’s first president ‘is studiously avoided’.

The chapter is a well-balanced assessment of this most controversial figure. It explores his organisational abilities and his importance in GAA circles in Ulster, showing how his long road to the first presidency of Fine Gael and, ultimately, his de-evolution into fascism played out.

The hopes that O’Duffy could become another Michael Collins for Fine Gael were quickly dashed. Given the earlier point made on Collins’ authoritarian tendencies, one wonders if Collins would have become another O’Duffy.

The authors state that the Blueshirt’s legacy to Fine Gael ‘is disproportionate to its involvement with the party’

Other welcome themes in the chapter focus of the minor elements which would make up Fine Gael in the Blueshirt era. The authors shine some light on overlooked figures such as Frank MacDermot of the National Centre Party, and how they entered the mix.

The Blueshirts, however is where the meat is, and the authors make a justified claim regarding Blueshirt criticism of Fine Gael in the modern period. They state that the shirted movement’s legacy to Fine Gael ‘is disproportionate to its involvement with the party’.[9] While true, it is ever present and shows little signs of being displaced.

As McGarry has noted the Blueshirts ‘remain the skeleton in Fine Gael’s cupboard’, with frequent abuse being thrown in the Dáil over the issue.[10] One wonders if this close study of the party might lead to some internal reckoning with this brief, yet murky episode.

Of course, Fine Gael are no special case regarding disproportionate slurs. Cheap point-scoring is a fact of political life. The ‘slightly constitutional party’ phrase which has dogged Fianna Fáil is a case in point. As recently as 2010 in the Irish Independent referenced this infamous piece of Irish political phraseology in the late historian Ronan Fanning’s column, which implored Fianna Fáil to have some credibility and call an election in the face of mounting economic and political turmoil.[11]

The fact of the matter is that parties born out of revolution and civil war cast a long, uncomfortable shadow. The chapter ends on a salient note, however, stating that ‘Without the Blueshirts, however, there might not have been a Fine Gael’.[12]

Foreign affairs

An interesting theme which weaves right through the heart of the book is the Fine Gael’s commitment to the international community. Something which current leading figures Simon Coveney and Leo Varadkar have repeatedly emphasised during the years-long Brexit debacle. This is addressed early on with the example of Cosgrave addressing the League of Nations in 1923. It also highlights John A. Costello’s international involvement with Imperial Conferences and the League of Nations.

An interesting theme which weaves right through the heart of the book is the Fine Gael’s commitment to the international community.

In later decades, Garret Fitzgerald’s role in Foreign Affairs is addressed. It was in this role he was said to have established ‘the reputation of Ireland as an enthusiastic member of the EEC’; while the party’s inclusion in the formation of the European People’s Party in 1976 is marked as one of a number of important milestones in Irish European integration.[13] Emphasis on this important theme throughout the book is unsurprising, given the ongoing farce which has gripped the neighbouring island this past several years (and counting).

Passages on Costello’s Inter-Party Governments focus on an area which has received far less attention than it deserves. The hugely important statement by Costello in Canada in September 1948 on withdrawal from the Commonwealth to become a Republic is framed as finally settling the question of Ireland’s constitutional status.[14] However, this would all depend which side of the dividing line one lived under. The authors acknowledge this predicament, arguing that among the celebrations ‘the spectre of Northern Ireland loomed’.[15] Not for the last time either.

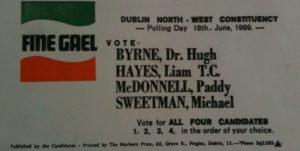

The enormous tasks which Costello’s second Inter-Party Government faced would have appealed to hardly anyone. Important figures, largely forgotten in popular memory such as Gerard Sweetman, the ‘vigorous conservative’[16] are highlighted, with the authors claiming his crucial role in the creation of the modern Irish economy has never been properly acknowledged.

In and out of government

The implosion of the second Inter-Party Government caused by economic issues as well as the IRA’s border campaign, (ultimately triggered by the withdrawing of Clan na Poblachta’s support for the government) is clearly laid out.

The authors argue that Fine Gael’s successes in this era have been obscured, stating: ‘the perceived failures of the second inter-party government and the bitterness generated between the coalition parties condemned Fine Gael to spending another sixteen years in the political wilderness’.[17]

Despite any successes the inter-party government notched up, there is, of course, no divine right to rule. Lee states that Fine Gael’s 1957 electoral defeat was self-inflicted, arguing that until Sweetman imposed an economic squeeze Fianna Fáil had shown no signs of a political challenge. The election result, he states was a vote of no confidence in the government, rather than an endorsement of a party led by the 74-year-old de Valera.[18] This would not be the last time Fine Gael snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.

Political continuity of the constitutional kind is yet another important theme which weaves its way throughout the book. The Cumann na nGaedheal/Fine Gael continuity is crucial to the story. However, there are attempts to draw this line back to the old Irish Parliamentary Party and steadfastness to constitutional nationalism, an ideology which supposedly set the party apart from the origins of their old rivals in Fianna Fáil.

It is arguable whether, as the book claims, Fine Gael came out of the constitutionalist tradition as it had stronger roots in physical force nationalism

The early years of the party witnessed figures from the IPP come on board, while in later years TDs such as Tom O’Higgins and Gerard Sweetman, and of course James Dillon could trace family lineages back to the glory days of the IPP. In more recent times much was made of John Bruton’s decision to hang a portrait of IPP leader John Redmond in the Taoiseach’s office during his leadership in the 1990s, an act viewed as an attempt to copper-fasten that IPP lineage.

This approach to the past is not without its problems. While there are undoubtedly pronounced links with the constitutional branch of nationalist politics, the party has its main roots in physical force nationalism, with many of the party’s founder members being ‘men of action’ in the revolutionary period. This is not a criticism of the book, however, it is more a comment on the disconnect in modern Irish political discourse which condemns more recent political violence while lauding figures who themselves were involved in extreme acts of political violence in the more distant past.

This is, of course connected to what is termed at one point in the book as the ‘Northern problem’. This problem comes to the fore during Liam Cosgrave’s years at the helm of the party. One could say that Cosgrave’s tenure was divided into two eras. One of exile and infighting and one of coalescence in the face of the unravelling situation in the North.

The increasing violence, which was spilling over into the South with regularity became the focal point of Liam Cosgrave’s years in power, indeed the first loyalist bombs in Dublin were argued to have saved his political career. One gets the sense that coverage of the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, the single biggest loss of life in the Troubles is not sufficiently explored here, save for the statement that the atrocity was not investigated properly.

Coverage of these incidents could have been greatly enhanced by inclusion of the reactions of some of the leading party figures. For example, the Fine Gael leader’s statement on the bombings demonstrated a level of empathy which crossed borders and communities. Cosgrave stated that the bombings helped ‘to bring home to us here in this part of our island what the people in Northern Ireland have been suffering for five long years’.[19] One feels that these passages could have been enhanced by such testimonies.

Aspects of the party’s engagement with the Northern Ireland conflict could have been more fully explored.

The murder of Billy Fox, the Fine Gael Senator in 1974 is described in shocking detail. This is also something which Brian Hanley has recently explored, showing a sporadic sectarian campaign against Fox going back to 1969 where it was claimed ‘A Vote for Fox is a Vote for Paisley’, as well as the erroneous Fianna Fáil-led accusations that Fox was a B-Special.[20]

It is unsurprising that the murder of a Fine Gael politician is covered. However, what is not referenced is Fox’s work in the Bogside in 1969 and his many criticisms of the British Army, which resulted in hate mail from Loyalists. Fox’s actions demonstrate someone who was more publicly engaged with the ‘Northern question’ than many within the party and help demonstrate why this was such a counterproductive killing for republicans.

The rise of one of the party’s iconic figures of the second half of the century, Garret Fitzgerald is explored in-depth, showing a dogged ambition and, indeed political ruthlessness from his earliest days within the party. Fitzgerald’s dowdy public persona, his pragmatic nature and his political family pedigree (parents who were from both parts of the island, and on opposite sides of the treaty split) provided him with a solid grounding to tackle many of the issues to be confronted during his time in power.

Fitzgerald’s relationship with Peter Prendergast in modernising the party is an important story here. Perhaps of more importance is Fitzgerald’s wife, Joan who was the closest political confidant of the man who led the party into a modern era.

Many pressing domestic and increasing international matters filled Fitzgerald’s plate in his years in charge, with the seemingly ever-present Charles J. Haughey occupying the same political space. Surprisingly, Fitzgerald’s ‘political and diplomatic triumph’, the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 is referenced only briefly. The claim of a ‘warm public reaction to the agreement’[21] is another one which depended on what side of the dividing line one lived on.

Alan Dukes’ tenure in the aftermath of Fitzgerald’s departure demonstrates a party coping, or more accurately, not coping with the loss of a figure who did much to revitalise Fine Gael’s political fortunes at home and abroad. The discontent which characterised the Duke’s era seeped into John Bruton’s years at the top of the party. This was a period, the authors state, where a culture of blame on the leader became the norm.[22]

The party was in the doldrums after Dukes, and Bruton had an unenviable task on his hands. The ‘Dublin Newsletter’ column in the Western People in April 1991 captured the public mood, telling of Bruton’s look of desperation as he tried to breathe new life into the party.[23] Bruton’s period in charge was a time of much flux in Ireland and within the party. Financial difficulties in the wake of the doomed 1990 Presidential Campaign added to the party’s many woes.

Bruton’s role in the developing peace process is well-known, and passages on this reveal that it was a huge challenge to the then Taoiseach, who it is said spent 70 to 80% of his time dealing with Northern Ireland. The authors cite his ‘natural antipathy to Sinn Fein’ as one of the challenges.[24]

This frosty relationship is also well-known. Catherine O’Donnell has noted this in her work on the Belfast Agreement and Southern Irish Politics, stating that Sinn Féin’s repeated endorsement of Fianna Fáil’s role in the process was in sharp contrast with ‘the negative impact of the Bruton administration’. On the back of this, she argues that Fianna Fáil experienced somewhat of an internal rejuvenation.[25]

Despite Bruton’s time spent on the peace process, it was domestic matters which led to the party’s downfall under him. A well-timed intervention in the 1995 Divorce Referendum was credited with swinging the result by a miniscule margin. However, this high was followed by damaging revelations about Minister Michael Lowry’s business dealings and the fallout from the controversy of women seeking compensation after being infected with Hepatitis C after blood transfusions.

The government’s image was damaged by Michael Noonan’s handling of the issue, especially Brigid McCole’s case. The Irish Times condemned Noonan at the time, stating that the Minister ‘who ought to have been primarily concerned to uphold the rights of a woman who had been fatally poisoned by a State institution was at least tacitly in agreement with the issuing of a threat to that woman’.[26]

Noonan, who would succeed Bruton at the top, is described as Fine Gael’s ‘unluckiest leader’ who never received that ‘new leader bounce’.[27] Dogged by the resurfaced Hepatitis C scandal among other issues, it seemed that he was permanently on the back foot. His tenure imploded with mass loss of seats in the 2002 election.

Interestingly the book highlights Noonan’s resignation interview for Six One News, where a bronze statue of Michael Collins stood behind his left shoulder. The authors argue ‘the presence of Collins was a reminder that the party was trapped in the past’.[28]

To the present

The Kenny years through to the current ‘Civil War coalition’ can hardly be described as history. Indeed, there is always the risk that bringing the past and the present together in a study like this that it will become disjointed.

Thankfully, this is not the case. Much in the final chapters is too close to merit historical analysis. That is not to say, however, that there is nothing to interest the purist historian. As always when it comes to Ireland, the past is never far away. This is certainly the case in the past two decades on this island.

The chapters dealing with Enda Kenny’s leadership are extremely fast paced, reflecting the extraordinary times. Numerous important themes are expertly weaved together, while the economic crash dominates the background. The spectacular collapse of Fianna Fáil perhaps brought small comfort now that immense pressures had to be reckoned with in dealing with the fallout from the economic turmoil.

These chapters are different than what has gone before. One gets the sense that Kenny is the hero of the piece, certainly in the first chapter. Descriptions of Kenny’s ‘natural bonhomie’, his youthful appearance when he took on the leadership role, and descriptions of a man who ‘loved the banter’ are at times uncomfortably close.[29]

The party’s huge victory in 2011 begins the second Kenny chapter, and where the ghost of Michael Collins still looms large in a now rejuvenated party. Youngest TD at the time, Simon Harris in a celebration speech paraphrased George Bernard Shaw’s famous letter to Michael Collins’ sister, Hannie, in which he implored her to ‘hang out your brightest colours’.

The memory of Collins is also present when Kenny became the first sitting Taoiseach since W.T. Cosgrave to address the annual Béal na mBláth commemorations in 2012. Kenny’s address noted that the fallen revolutionary leader was not afraid to take difficult decisions. In the face of mounting austerity, the authors argue that the ‘ghost of Collins was used to add legitimacy to the policies the government were pursuing’.[30] This curiously contrasts to a decade previously where the ousted Noonan, watched over by the statue of Collins had left a party which was ‘trapped in the past’.

Leo Varadkar’s term at the helm brings the book up to the modern day, with the bruising 2020 election campaign and Brexit being the focal points. With the remove of only a few months the brutality of that election campaign is clear.

Again, history was never far from the surface. The RIC controversy is mentioned. But as they point out, it is hard to determine how much of a factor that was in the election result. The 1932 election is also recalled, with the authors contemplating if Varadkar, while at the election count was thinking about the ‘unknown quantity’ of Sinn Fein, like W.T. Cosgrave viewed Fianna Fáil in 1932.[31]

This book is certainly not the puff-piece in favour of Fine Gael that sections of the online community predicted, the authors are not reluctant to criticise either individual actions or policy decisions and it is tremendously well written.

The title of the final chapter ‘The End of Civil War Politics’? could be the subject of a book in its own right. As noted in the closing passages of the book, despite the symbolic hanging of the portraits of Collins and de Valera side by side in the Taoiseach’s office, there are those who think that the narrowing of this century-long divide is a temporary phase. If this current study has taught us anything, it is that political coalitions in Ireland can collapse at any point. Therefore, a bet on the new status quo would be an unwise choice.

Despite any misgivings over the title, it is certainly not the puff-piece in favour of Fine Gael that sections of the online community had pegged it to be. There are rare occasions, however when one could interpret the book as pulling for certain party figures. Regardless of those perceptions, the authors are not reluctant to criticise either individual actions or policy decisions.

It is a tremendously well written book. At 418 pages it flows extremely well and is very accessible, even to the uninitiated. The fast-paced and precariousness of political life is apparent throughout, especially in the later decades when increased European integration led to juggling issues on multiple fronts.

The unanswered questions around the partition of the island influenced many within the party, who responded with varying degrees of enthusiasm. That will certainly intrigue people unfamiliar with parts of the party’s history. No doubt there will be some who will be put off such a study due to its subject matter. Conversely, that same subject matter will undoubtedly attract many to buy it.

Overall, this is an interesting and engaging look at the history of one of the major parties within the Irish state. Given the public interest around the Decade of Centenaries this book, which in many ways examines the political legacy of that period, should sell very well.

References

[1] Ciara Meehan, ‘Fine Gael’s Uncomfortable History: The Legacy of Cumann na nGaedheal’ in Éire-Ireland, vol. 43, nos. 3&4, ( Fall/Winter 2008), pp 253-266.

[2] Samuel Brunk and Ben Fallaw (eds.) Heroes and Hero Cults in Latin America (Austin, 2006), p. 3.

[3] John Dorney, ‘Michael Collins: The Dictator’? https://www.theirishstory.com/2017/08/19/michael-collins-the-dictator/#.X5KrA9ZKjIU

[4] Seán Kennedy, ‘CULTURAL MEMORY IN “MERCIER” AND “CAMIER”: The Fate of Noel Lemass’ in Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd’hui , 2005, Vol. 15, (2005), pp 117-129.

[5] Fergus Campbell and Tony Varley (eds.), Land Questions in Modern Ireland (Manchester, 2013), p. 58.

[6] Michael McDowell, ‘The Questionable Value of Catholic Socio Economic Theory’ in An Irish Quarterly Review, vol. 80, no. 319 (Autumn, 1991), pp 253-258.

[7] Adrian Hoar, In Green and Red, The lives of Frank Ryan (2005), p.88.

[8] Stephen Collins and Ciara Meehan, Saving the State: From Collins to Varadkar (Dublin, 2020), p. 396.

[9] Collins and Meehan, Saving the State, p. 44.

[10] Fearghal McGarry, Eoin O’Duffy: A Self-Made Hero (Oxford, 2005), p. 269.

[11] Irish Independent, 7 Nov. 2010

[12] Collins and Meehan, Saving the State, p. 45.

[13] Ibid, pp 169-180.

[14] Ibid, p. 55.

[15] Ibid, p. 59.

[16] J.J. Lee, Ireland 1912-1985: Politics and Society (Cambridge, 1989), p. 326.

[17] Collins and Meehan, Saving the State, p. 90.

[18] Lee, Ireland 1912-1985, pp 326-328.

[19] Taoiseach Condemns Bombings In Dublin And Monaghan 1974, RTE Archives (https://www.rte.ie/archives/2019/0508/1048218-taoiseach-on-dublin-and-monaghan-bombings/)

[20] Brian Hanley, The Impact of the Troubles on the Republic of Ireland, 1968-79: Boiling Volcano? (Manchester, 2019), pp 141-152.

[21] Collins and Meehan, Saving the State, p. 217.

[22] Ibid, p. 247.

[23] Western People, 3 Apr. 1991.

[24] Collins and Meehan, Saving the State, pp 268-269.

[25] Catherine O’Donnell, The Belfast Agreement and Southern Irish Politics (London, 2009), p. 215.

[26] Irish Times, 2 Aug. 1997.

[27] Collins and Meehan, Saving the State, p. 284.

[28] Ibid, p. 294.

[29] Ibid, pp 297-301.

[30] Ibid, pp-330-345.

[31] Ibid, p. 399.