The Whitefeet: Social Conflict in Kilkenny and Laois Before the Famine

By Terry Dunne

There is a great sense of prescience to what English Radical M.P. George Poulet Scrope wrote eleven years before the Great Famine. In 1834 Scrope claimed that: ‘

[b]ut for the salutary dread of the Whiteboy association, ejectment [evictions] would desolate Ireland and decimate her population, casting forth thousands of families like noxious weeds rooted out of the soil on which they have grown […] the Whiteboy system is the only check on the ejectment system […].’[1]

Similarly, to historian James S. Donnelly the mass clearances (‘ejectments’) of the Famine happened in part because of ‘the virtual collapse of the tenant capacity for effective resistance’.[2] For ‘the Whiteboy system’ read ‘effective resistance’ and vice versa.

In the early nineteenth century, secret societies resisted the move towards ‘clearing’ densely populated estates and replacing tenants with livestock.

A lot of what we associate with the Great Famine is explicable largely in terms of a pre-existing programme to transform agriculture. The workhouse, assisted emigration and the notorious quarter-acre or Gregory clause that denied relief to landholders, were all facets of this.

This was a complex situation and there were also legislative measures directed against landlords aiming to transfer the costs of poor relief on to them and to facilitate the sale of heavily indebted estates. These too had similar transformative intent.[3]

The goal was elaborated by George Cornwall Lewis, one of the bureaucrats behind the workhouse system, as to:

‘alter the mode of subsistence of the Irish peasant : to change him from a cottier living upon land to a labourer living upon wages : to support him by employment for hire instead of by a potato-ground. This change can only be effected by consolidating the present minute holdings, and creating a class of capitalist cultivators, who are able to pay wages to labourers, instead of tilling their own land with the assistance of the grown-up members of their family. But landlords cannot consolidate farms because they cannot clear their estates.’[4]

This was a programme of proletarianisation, aimed at creating a class of wage labourers on the one-hand, and on the other, large-holders capable of generating the profits necessary to re-invest in the latest technologies. The big change in this period was a switch from a strong emphasis on cereals to a predominance of livestock. This was not the goal of policy-makers but also required a change to comparatively larger farms.

The barrier to farm consolidation was what Scrope called ‘the Whiteboy system’ — a succession of insurgent movements dating from the 1760s onwards. This article is a case-study of one of them — the Whitefeet in Kilkenny and the Queen’s County (present-day Laois) in the early 1830s. First, there will be a broad introduction, and then there will be a recounting of specific incidents of Whitefeet agrarian violence, and, finally, some discussion of the response of liberal political leaders.

The Whitefeet movement

When talking about a movement like the Whitefeet we are talking about something much looser and more informal than a modern political party or trade union. It is more like a common label put on a common style of action, in modern terms more like a youth sub-culture than a political organisation.

There is evidence of the ritual of formal organisation, such as oaths and passwords, what we would associate with a secret society, but there is little evidence of any elaborate organisational structure, mostly there just seems to have been local bands in different areas. The term ‘secret society’ is more appropriate to the quite different Ribbon societies more often found in the northern parts of the island.[5]

Geographically speaking the districts most associated with the Whitefeet were those along the western side of the river Barrow, from Portarlington down to Rosbercon (on the opposite side of the bank from New Ross), and especially the hill country of Slievemargy/the Castlecomer plateau, and also along the southern borders with Kilkenny more generally.[6]

The Whitefeet were a combination of poor rural men who tried to prevent evictions, ‘land grabbing’ and high rents.

A ballad associated with the Whitefeet and collected in Carlow in the mid-1830s namechecks Ballyroan and Timahoe in south Laois as well as Kilkenny.[7]

Almost all of our sources for the Whitefeet are the records of their opponents — the reports of magistrates and constabulary officers and the estate papers of landlords and land agents. Consequently, there is much we do not know.

What was often recorded was violence, to some extent because this is what the authorities were interested in, but also because this was what was visible to them. Although there is this skewing of the record, nonetheless it must be recognised that the Whitefeet was indeed a violent movement, albeit one more given to assault and intimidation than assassination. However, these were violent times; this was still a world of flogging, duelling and public hanging. Not to mention the profound structural violence of inequality, poverty and dispossession.

Faction fighting

The Whitefeet began as a fighting faction, fighting with a group called the Blackfeet, from around about 1827 onwards.[8] Faction fighting was large groups of young men assembling for combat, usually with sticks.[9]

Factions united along lines of kin, confession, territory, occupation or class.[10] There are various legendary accounts of the origin of the names of the two factions.

These include a dispute during the construction of Maryborough gaol with the stonemasons on one side and the labourers on the other. The masons’ feet were white from lime hence ‘Whitefeet’.[11]

The Whitefeet began as a fighting faction, fighting with a group called the Blackfeet, from around about 1827

This is interesting in that another account blames ‘rambling masons’ for bringing the Whitefeet system to the parish of Ballynakill in 1827. [12] A perhaps more implausible tale has it that the name was in reference to the white stockings of a faction leader, though at least one other fighting faction was named after a leader’s sartorial choice.[13]

There was at times a socio-political aspect to faction fighting, but the simple recreational aspect should not be overlooked. The fair of Dysart was particularly associated with faction fighting.[14] Dysart lies near the main road between Stradbally and Portlaoise, close to the Rock of Dunamaise. Whitefeet versus Blackfeet faction fights were also recorded in Tullamore and Philipstown (present-day Daingean),[15] Mountrath and Mountmellick,[16] as well as Emo.[17] There was some suggestion by the authorities that the purpose of the Blackfeet was defensive.[18]

It is notable that many of those locations of faction fights were not in the Whitefeet heartland. Were the Blackfeet trying to keep the Whitefeet out? The Caravats versus Shanavests feud in Waterford and adjacent districts was one between a sort of labourers’ trade union and a farmers’ vigilante group.[19]

We do not know enough about the Blackfeet to clearly say that this was also the case with the Whitefeet versus Blackfeet strife.

From fighting faction to agrarian movement

From 1829 onwards the Whitefeet faction was associated with whiteboy or rockite type activity, the terms whiteboy or rockite were derived from earlier quite famous movements (the Whiteboys in Tipperary in the 1760s, and the Rockites in Munster in the early 1820s).

In this later context the best recorded Whitefeet actions were violence over land occupancy (frequently directed against other tenants); seizure of firearms; and compelling people to take oaths, for example oaths to quit land or to raise wages.

However, both oaths and the requisitioning of guns had, to the state authorities, dangerous political overtones. It is not really possible to quantify to what extent any particular type of action was happening for the reason that the people doing the recording were more interested in some actions than others.

From 1829 onwards, Whitefeet actions intimidation of ‘land grabbers’; seizure of firearms; and compelling people to take oaths, for example to quit land or to raise wages.

The shift from being faction fighters to being whiteboys or rockites was to do with attempts, on the part of landlords and land agents, to re-organise particular estates or parts of an estate.[20]

The context: landed estates in the Queen’s County and north Kilkenny

By estate is meant here the entire property of the landlord, including the tenanted lands, not just the demesne, or area around the big house, which is what people nowadays frequently refer to as ‘the estate’.

Particularly noted as an early site of conflict was the Cassan estate, which was centred just a little way to the south-east of what is now Portlaoise.

Conflict, to varying extents, was recorded on many other estates, including the Lyster estate beside Durrow; on the Lansdowne estate at Luggacurren; on that part of the Cosby estate south of Timahoe (known as Fossey); on the property leased by the Grand Canal Company at Newtown (and on lots of properties adjacent to Newtown, mostly small estates or middlemen holdings); and on the Wandesforde estate, just over the border from Newtown into county Kilkenny. The core area was the up-land coal-mining district of Wolfhill, Newtown, and Castlecomer.

Ownership of the land was concentrated in a few landed families, some of whom also had interests in businesses such as coal-mining, at Castlecomer

This was quite a well-populated area at the time, and, was notably lacking in local state administrative structures on the Queen’s County side of the border — the Kilkenny side was a little different in this respect.

While changes, or attempted changes, on specific estates gave the movement its impetus, it soon spread to a wider area and adopted a wider agenda. Also it should be stressed that despite the important role of particular landlord versus tenant conflicts, much of the animus and violence was directed towards tenants who had taken land to which other tenants regarded themselves as having a right to.

Arms raids, oaths and land disputes

As has already been stated, raids for firearms were a regular Whitefeet action. For example, in the middle of April 1832 the area around Milford and Clogrennan in county Carlow was systematically scoured for arms by a group which had come down from the hills.[21]

As has already been stated, raids for firearms were a regular Whitefeet action. For example, in the middle of April 1832 the area around Milford and Clogrennan in county Carlow was systematically scoured for arms by a group which had come down from the hills.[21]

One firearm raid that went badly wrong was on the house of John Bailey, in Inch, which is just north of Stradbally, in March 1832.[22] Bailey and his son James offered resistance, and the assailants shot John Bailey dead. John Bailey was already being boycotted as a recipient of tithe.

Tithe was a tax for the Church of Ireland, but the tithes to an area could be leased or even sold, which meant the right to collect that tithe was actually in the hands of laypeople rather than the clergy. However, the desire for firearms was the immediate cause of this killing rather than the tithe issue.

Whitefeet often raided homes at night to seize firearms. Most gun owners handed over their weapons, but a few were killed when they resisted.

The usual response when faced with Whitefeet was for gun owners to simply hand their weapons over. People were criticised by the newspapers and the police for doing so, at the time the expectation was that you would stand your ground.

However, against the likes of the Whitefeet this was a bad idea, individuals who resisted them over any specific issue could be the victims of campaigns of violence and intimidation which could last for months. It was quite untypical for a raid for firearms to end with fatalities.

In the early-nineteenth century oaths were of great political and religious significance. The practise of compelling oaths meant that the Whitefeet would force someone to kneel, or to put their hand on a prayer book, or to do some similar ritual, and then to swear to carry out a particular course of action.

That might be swearing to not give information to the local magistrate or it might be swearing to come to a particular agreement in a dispute over land.

The big land occupancy disputes, involving hundreds of people, were on estates which were undergoing a landlord-directed process of change. These might have actually been relatively peaceful — though not on the Cassan estate which was, according to some versions, the site of the beginning of the general conflict.[23]

The first incident in the coal-mining area was some arson to do with threatened evictions on land which was part of the Hanlon colliery at Modubeigh, near Wolfhill.[24] Conflict on the Wandesforde estate around Castlecomer in Kilkenny was often more to do with coal-mining than land.

However, aside from these larger disputes there was a whole host of smaller disputes. Once the movement got going, years old disagreements and grievances over land were reawakened. For example, a family called Farrell, residing near Ballyragget in county Kilkenny, were attacked, and one of the several Farrell brothers was killed by a single gunshot to the head at point-blank range.[25]

They held land from which another tenant had been evicted twelve years earlier. This was on the Kavanagh estate, which was centred in Borris, county Carlow. It was unusual that things would escalate to killing, more typical were beatings or general attempts at intimidation.

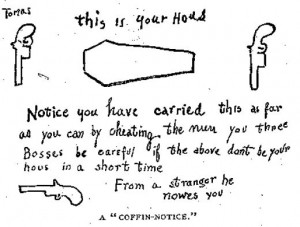

Threatening letters

A popular mode of intimidation was the so-called threatening letter or threatening notice.[26] These were usually short usually hand-written documents either left in a public place as a general warning, such as outside the church gate, or left where a particular target would find it, such as at one of the windows of their house.

A popular mode of intimidation was the so-called threatening letter or threatening notice.[26] These were usually short usually hand-written documents either left in a public place as a general warning, such as outside the church gate, or left where a particular target would find it, such as at one of the windows of their house.

There were exceptions to this general pattern. There were printed notices: one such demanding that farmers let some of their land to their labourers at the same rate they receive it from their landlords was printed and widely distributed around Kildare in 1832.[27]

There were notices openly delivered to their targets — there was clearly some symbolic value to having demands in written form. In Clough, in county Kilkenny, there was an episode were farmers targeted in public notices issued their own public notices conceding the original demands a week later.[28]

Below is an excerpt from a notice posted at the church in Mayo (a village in south-east Laois) in October 1831:

‘. . . you high in authority, do not be oppressive or tyranizeing or if ye do ye shall not exist. It touches his honrs feelings very much to hear the manner in which numbers are oppressed by tyrants. But let them understand that if they do not Refrane from all such, they will Be sorry and heartly sorry at the moment of a untimely Death. His honor hopes that he will not be put to the trouble of marching his men to subdue tyrants in this Quarter of the country, ye may think that ye live remote from him or his delegates, But be asured of it ye do not. Certainly ye will find the result of this notice if ye do not Desist from the forementioned abuses.

By order of his Honor Capt. Rock & Starr’.[29]

Quite typical features were the legalistic language, like ‘his Honor’, and the claim to represent an elaborately organised institution with a wide geographic reach, like ‘ye may think that ye live remote from him or his delegates, But be asured of it ye do not’.

Also very typical was the pseudonym ‘Capt. Rock’ and very typical was the fact that this pseudonym originated in a different time and place.

The pseudonym Captain Rock was originally associated with the Rockite movement, mostly in Limerick and Cork and adjacent counties in the early 1820s. Threatening letters are very important as a source, because most of the evidence we have for a movement like the Whitefeet does not come from the movement itself, but from their opponents in the constabulary and the magistracy.

Political responses

In the late-nineteenth century and early-twentieth century Home Rule politicians and Irish Republican Brotherhood activists rallied around the agrarian movements, and, indeed, often led them. The situation in the 1820s and 1830s was quite different, the proto-nationalist liberal movement was much less engaged with agrarian issues — opposition to tithe was a notable exception to this disengagement.

The key political movement of that time is of course associated with the name Daniel O’Connell. In the 1820s the main agitation was for Catholic Emancipation and in the early 1840s for Repeal of the Union.

The main issue in the early 1830s was tithe, the tax for the support of the Church of Ireland. I refer to this movement as the liberal movement rather than the O’Connellite movement for the reason that O’Connell was not as centrally involved in the early 1830s as he would be later or was earlier, and that as there were actually people involved who would not have regarded themselves as followers of O’Connell.

Daniel O’Connell and his Repeal movement were not, in general, interested in agrarian issues.

The Tithe War was socially and geographically distinct from the Whitefeet. The anti-tithe mobilisation was a much more broad-based and cross-class movement. Indeed, the Tithe War was occasioned in part by a reform which made grasslands eligible for tithe and hence made this more of an issue for precisely those large-holders who stood to benefit from clearances. Regarding place, a further difference can be seen, with, for instance, the Whitefeet predominant in north Kilkenny, while the Tithe War was the main mobilisation in the south of the county.[30]

At the same time this distinction should not be drawn too sharply, the struggle against tithe certainly drew on some of the Whiteboy repertoire of violent direct action. In general, the Tithe War was more a precursor of late-nineteenth century movements — in terms of broad social composition, diverse tactical repertoire and intersection with political agitation.[31]

Leading lights in the opposition to tithe included Patt Lalor, M.P. for the Queen’s County between 1832 and 1835, and Bishop James Doyle, bishop of Kildare and Leighlin from 1819 until his death in 1834. Doyle was one of the most eminent liberal activists of the day and was also an important reformer within the Catholic church.

The Kildare and Leighlin diocese included within it a sizeable portion of the Queen’s County. Doyle issued three pastoral letters against the Whitefeet movement, in November 1829, November 1831, and May 1832.

The Catholic clergy supported the campaign against paying tithes to the Protestant Church, but discouraged their flock from becoming involved with the Whitefeet and similar societies.

These pastoral letters were to be, at least in part, read out by priests at mass, and the November 1831 one was printed up by the local liberal newspaper the Carlow Morning Post for cheap distribution in the relevant areas. Doyle would also show up to preach in effected parishes.

The conundrum for Doyle was that the same liberal ideology which he held, and which justified the contestation with the state and ‘Protestant Ascendancy’ that he took part in, could equally serve the same purpose for the struggle of the Whitefeet. A telling excision was made in the published version of his 1829 pastoral letter.[32] It reads:

‘What I wish to impress upon you is the general rule taught us by our own reason, which general rule says that associations or combinations not authorised by law are not justifiable’. [33]

However, the original unpublished version included the qualifier:

‘. . . unless in those cases where oppression or want is insupportable or extreme, and that the laws or the government after having been respectfully applied to neglect or refuse to remove the oppression or supply the extreme want’.[34]

In the letters of 1829 and 1831 Doyle attempted to dissuade his flock from the course some of them had gone down in the Whitefeet. The letter of May 1832 was curter, and rather than attempting to persuade, ordered the organization of coercion.

While the letter itself was concerned with imposing stringent confessional terms on Whitefeet participants, an adjoining covering letter to the clergy advised them to:

‘exhort and assist by every means in your power, the owners of property, and the well-disposed of every class of your parishioners, to unite in their own defense; to form themselves in concert with the constituted authorities, into armed associations for the protection of persons and property — to patrol the country by day and by night whilst necessary — to detect and apprehend, or to terrify into better habits the evil-doers, who could then safely be dismissed from employment, should they fail in the duties they owe to God and to their employers’.[35]

The issue of forming a voluntary association to put down the Whitefeet was a source of political contention in the Queen’s County. The proposal had also been raised by Patt Lalor.

Note that Lalor’s proposed association was to report directly to Dublin Castle, rather than to the local magistracy (i.e. local gentlemen tasked with the upkeep of law and order).[36]

The idea of a volunteer force was not that outlandish at all and in fact quite in keeping with the British constitution, more so indeed than the idea of a professional police force.

The problem essentially was this particular force would be one predominantly consisting of Catholic farmers, worse yet Catholic farmers who were in a struggle with the Established Church over tithe, and more generally with the Ascendancy over the distribution of political power. The magistracy were in large part chips off the same block as that Dublin Corporation that declared in 1792 for the status quo forever:

‘A Protestant King of Ireland, A Protestant Parliament, A Protestant Hierarchy,Protestant Electors and Government, The Benches of Justice, The Army and the Revenue, Through all their branches and details, Protestant; And this system supported by a connection with the Protestant Realm of Britain.’[37]

The fact that men of property were divided into liberal and conservative factions made it much more difficult for them to deal with a movement like the Whitefeet. In addition to the efforts of Bishop Doyle, Tom Steele, a minor Clare landowner and lieutenant of Daniel O’Connell, conducted a propaganda campaign against the Whitefeet in Kilkenny in February and March 1833.[38]

Decline and aftermath

From 1833 onwards, the rate of reported Whitefeet actions goes into steep decline. As well as the efforts of liberals as detailed above, they faced a response from the state — the drafting-in of extra soldiers and police, special trials, curfew, new emergency repressive legislation, searches for arms, and public executions. However, landlords moderating their attempts to re-arrange their estates was probably a decisive factor in this relative decline in overt violent conflict.

From 1833 onwards, Whitefeet activity goes into steep decline. Partly due to state repression, but also to some landlords moderating their policies.

There were two major government studies of social conditions in Ireland between the mid-1830s and the mid-1840s, the Poor Inquiry and the Devon Commission. These reports evince a counter-tendency to farm consolidation at least in the southern and central whiteboy heartland from Waterford up to the King’s County (present-day Offaly). That counter-tendency to clearance was the fear of a violent reaction from prospective evictees.[39]

Then, in the late-1840s, the potato blight made the impossible possible. The Great Famine had a big impact in this area — the decline in population in the Queen’s County at 28%, was comparable to that in the Western counties, such as Clare, which experienced a 25% drop.[40] There is much focus on the discontinuities of the nineteenth century but there were also continuities. In later decades the main zone of agrarian social conflict was more westerly, but counter-tendency to landlord control came back,[41] and the whiteboy repertoire continued, albeit at a comparatively subdued tempo.[42]

Terry Dunne studies agrarian social movements, and has a Phd. in sociology from Maynooth University. Click here for his podcast Peelers & Sheep.

References

[1] Quoted in John E. Pomfret, The Struggle for Land in Ireland 1800–1923 (Princeton, 1930), p. 24.

[2] James S. Donnelly Jr., ‘Mass eviction and the Great Famine’ in Cathal Póirtéir (ed.), The Great Irish Famine (Cork, 1995), p. 156. There was still resistance, but comparatively little.

[3] For the intellectual context see Peter Gray, Famine, Land and Politics: British Government and Irish Society 1843-50 (Dublin, 1999).

[4] George Cornewall Lewis, On Local Disturbances in Ireland; and on the Irish Church Question (London, 1836) p. 319.

[5] Kerron Ó Luain, ‘‘To get up an anti-Fenian society in this country’: Ribbonism and republicanism in Ulster, 1850-1867’ https://www.theirishstory.com/2018/05/11/to-get-up-an-anti-fenian-society-in-this-country-ribbonism-and-republicanism-in-ulster-1850-1867/#.X9eOuLfgrIU, accessed 14/12/2020.

[6] Report from the Select Committee on the State of Ireland, with the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix, and Index, p. 82, H.C. 1831–32 (677), xvi.1 (hereafter cited as State of Ireland); for the southerly expansion down to Rosbercon see: Kilkenny Moderator, 13 Mar. 1833; Kilkenny Moderator, 16 Mar. 1833; Kilkenny Moderator, Mar. 27 1833; Kilkenny Moderator, 6 Apr. 1833.

[7] The Petrie Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland, ed. David Copper (Cork, 2002), pp 132-133; Captain Carder, online at www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZY7Tgce2F28, accessed 06/12/2020.

[8] State of Ireland, p. 218.

[9] I look at faction fighting and popular culture in relation to whiteboyism here: https://www.rabble.ie/2018/09/19/of-riots-rituals/

[10] James S. Donnelly Jr. ‘Factions in pre-Famine Ireland’ in Audrey S. Eyler and Robert F Garratt (eds) The Uses of the Past: Essays on Irish Culture (Newark & London, 1988) p. 116.

[11] Memoranda William Gosset 17 June 1832 (N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./1832/1040).

[12] State of Ireland, p. 251.

[13] State of Ireland, p. 180.

[14] Carlow Morning Post, 22 July 1830; State of Ireland, p. 180; Jonah Barrington, Personal Sketches of His Own Times Vol. 2 (London, 1869) pp. 340‒344;, Lochlainn Ó Tuairisg, ‘Whiteboys and Faction Fighters in Pre-Famine Ireland’ in History Matters: Selected Papers from the School of History Postgraduate Conferences 2001‒3 (Dublin 2004) p. 101.

[15] James Crawford to John Harvey 3 Jan. 1832 (National Archives of Ireland, Chief Secretary’s Office/Registered Papers/1832/43). Hereafter N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P. The Chief Secretary’s Office papers are currently being re-catalogued – all references to the 1832 papers are given in the old system, other years are in the new system with the old system in adjacent brackets. James Crawford to John Harvey 3 Oct. 1832 (N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./1832/1800/11); James Crawford to John Harvey 24 Oct. 1832 (N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./1832/1800/89).

[16] Leinster Express, 1 Oct. 1831.

[17] John Harvey 17 Oct. 1830-24 Oct. 1830 (National Archives of Ireland, Chief Secretary’s Office/Registered Papers/Outrage Reports/1830/449) (original reference 1830/H87). Hereafter N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./O.R..

[18] D. O’Donoghue to William Gosset 14 June 1832 (N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./1832/1037); H.B. Wray to John Harvey 24 May 1830-7 June 1830 (N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./O.R./1830/401) (original reference H40); State of Ireland, p. 176.

[19] Paul E. W. Roberts, ‘Caravats and Shanavests: Whiteboyism and Faction Fighting in East Munster,

1802‒11’ in Samuel Clark, and James S.Donnelly, Jr. (eds.) Irish Peasants: Violence and Political Unrest 1780‒ 1914 (Dublin, 1983) pp. 64‒68, 94‒98.

[20] I look at these estate conflicts in more detail in the following:

‘Gentlemen Regulators: Landlord/Tenant Conflict and the Making of Moral Economy in Early Nineteenth-Century Ireland’, Rural History: Economy, Society, Culture vol. 31 no. 1 (April 2020), 17‒34. doi: 10.1017/S0956793320000011 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/rural-history/article/gentlemen-regulators-landlordtenant-conflict-and-the-making-of-moral-economy-in-early-nineteenthcentury-ireland/E4A52DDCE5DCB24A4B6074B261059DE6/share/7a9e2817350f319e0055d022f3c7c599a931edba ; ‘“Humour the People”: Subaltern Collective Agency and Uneven Proletarianization in Castlecomer Colliery 1826‒34’, Éire-Ireland vol. 53 nos. 3/4 (Fall & Winter 2018), 64‒92. doi: 10.1353/eir.2018.0013. Also see the short film of a seminar presentation here: https://youtu.be/JKzxALTFroE, accessed 14/12/2020.

[21] Kilkenny Moderator, 21 Apr. 1832.

[22] James Mongan, A Report of the Trials before the Right Hon. The Lord Chief Justice and the Hon. Baron Sir Wm. C. Smith, Bart. at the Special Commission, at Maryborough, commencing on the 23rd May, and ending on the 6th June (Dublin, 1832) pp. 18-34.

[23] State of Ireland, p. 180; D. O’Donoghue to William Gregory, 5 Feb. 1830 (N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./O.R./1830/368) (original reference H7).

[24] John Harvey to William Gregory, 4 May 1829 (N.A.I., R.P./O.R./1829/335) (original reference H26).

[25] D. T. Osborne to William Gosset, 20 Feb. 1832 (N.A.I., C.S.O./R.P./1832/404); Kilkenny Moderator, 22 Feb. 1832.

[26] I examine threatening letters in the following works: ‘“Wolf Hill I dread you”: Threatening Letters and Other Alternative Documentary Sources for the Leinster Colliery District’, Journal of the Mining Heritage Trust of Ireland 16 (October 2018), 33‒37. www.mhti.org/uploads/2/3/6/6/23664026/wolf_hill_i_dread_you-leinster_colliery_district._dunne_t.__2012_.pdf ; ‘Letters of Blood and Fire: Primitive Accumulation, Peasant Resistance and the Making of Agency in Early Nineteenth-Century Ireland’, Critical Historical Studies vol. 5 no. 2 (Spring, 2018), 45‒74. doi.org/10.1086/697031 ; ‘‘We the Regulators of the County of Kilkenny’: Threatening Letters and Social Conflict in the 1830s’, Old Kilkenny Review (2018), 119‒127; ‘The Law of Captain Rock’ in Kyle Hughes and Don MacRaild (eds), Crime, Violence and the Irish in the Nineteenth Century (Liverpool University Press, 2017) 38–52; ‘Captain Rock’ in John Cunningham and Emmet O’Connor (eds), Studies in Irish Radical Leadership: Lives on the Left (Manchester University Press, 2016) 9‒21.

[27] Notice reproduced here: Stephen Randolph Gibbons, Captain Rock, Night Errant: The Threatening Letters of pre–Famine Ireland 1801‒1845 (Dublin, 2004), p. 240

[28] Kilkenny Moderator, 28 Mar. 1832.

[29] Leinster Express, 22 Oct. 1831.

[30] John Harvey to William Gosset, 27 Mar. 1832 (N.A.I., R.P./1832/587).

[31] The classic account of the Tithe War is in: Patrick O’Donoghue, ‘Opposition to tithe payments in 1830‒31’, Studia Hibernica 6 (1966) 69‒98; Patrick O’Donoghue, ‘Opposition to tithe payment in 1832‒3’, Studia Hibernica 12 (1972) 77‒108.

[32] Thomas McGrath, The Pastoral and Education Letters of Bishop James Doyle of Kildare and Leighlin, 1786‒1834 (Dublin, 2004) pp. 284‒296.

[33] Ibid. p. 287.

[34] Ibid. p. 287.

[35] Ibid. p. 337

[36] Michael G. O’Brien, The Lalors of Tenakill 1767‒1893 (M.A. Thesis. St. Patrick’s College Maynooth. August 1987) p. 34.

[37] Fergus O’Ferrall, Catholic Emancipation: Daniel O’Connell and the birth of Irish Democracy 1820‒30 (Dublin, 1985) p. 15.

[38] Kilkenny Journal, 30 Jan. 1833; Kilkenny Journal, 2 Feb. 1833; Kilkenny Journal, 9 Feb. 1833; Kilkenny Journal, 15 Feb. 1833; Kilkenny Journal, 6 Mar. 1833; Kilkenny Journal, 20 Mar. 1833.

[39] See the articles on estate conflicts cited above.

[40] Joan Flynn, The Famine Years in Queen’s County 1845‒1850 (M.A. Thesis. St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth, August 1996) p. 2.

[41] Paul Bew, Land and the National Question in Ireland 1858‒82 (New Jersey, 1979) p. 9.

[42] For an example see: Niall Whelehan, ‘Labour and agrarian violence in the Irish midlands, 1850‒1870’ in Saothar 37 (2012) 7‒17. Indeed, the illustrations adjoining this article are of south Ulster in the 1850s.