Some Thoughts on the Truce – 100 Years On

By John Dorney

Today, July 11, 2021, marks 100 years since the final day of the Irish War of Independence. A Truce, which had been agreed by both British and Irish representatives in Dublin’s Mansion House on July 8, came into effect at noon on the eleventh of July 1921.

As such, it is in a sense, Ireland’s equivalent of Armistice Day, November 11, when hostilities of the First World War were ended. And indeed, since 1986, the nearest Sunday to July 11 has served as the Irish state’s National Day of Commemoration which; ‘remembers all Irishmen and Irishwomen who died in past wars or on service with the United Nations’.

The official commemorations of the centenary this year appear to have been fairly subdued, mostly due to the ongoing restrictions due to the worldwide Covid-19 pandemic.

But at the best of times, July 11 is an ambiguous commemoration. It does not represent anything as uplifting as victory or Irish independence. The Truce was a pause in fighting, not a political settlement and that settlement, the Anglo-Irish Treaty set off another round of fighting between Irish nationalists from 1922-23 as well as the ongoing conflict over the partition of Ireland.

Even in the short term, there was no release of republican prisoners or evacuation of British forces. The Royal Irish Constabulary remained the police force. None of this would change until after the signing of the Treaty in December 1921.

So what is the significance of the Truce?

As well as being an end, for the time being at any rate, to political violence and guerrilla war in Ireland, the Truce was an important watershed.

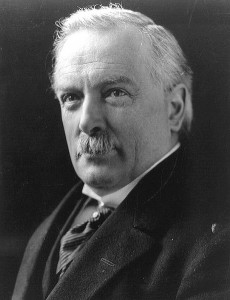

It marked the failure of Prime Minister Lloyd George’s twin policies of coercion and two Home Rule parliaments, one in Dublin the other Belfast, to settle ‘the Irish question’. Lloyd George had hoped that by military suppression of the IRA and by elections to the two prospective Parliaments in May 1921, the ‘moderates’ in Irish nationalist and republican ranks could be separated from the ‘extremists’ and a deal concluded with the former.

None of these things had come to pass by late June 1921. In May 1921, Sinn Féin had won every seat (except four Unionists representing Trinity College) in Southern Ireland, unopposed. The Home Rule parliament of Southern Ireland was stillborn. The Irish Parliamentary or Home Rule, Party had declined even to stand in the elections, whether through desire not to split nationalist ranks or through intimidation, or both, effectively ceding its right to be consulted about a political settlement.

Southern Unionists, effectively cut adrift by their Ulster brethren, had by June 1921 become persuaders for a peace settlement and their leader Lord Midleton (John Broderick) had become one of the chief mediators between the Irish Republicans and the British government. This again was informed both by knowledge that defence of the Union was no longer a viable position in the south of Ireland and by the fact that the IRA was increasingly targeting unionist property (especially in Munster) in reprisal for Crown forces’ destruction of civilian homes.

So when, on June 24 1921, Lloyd George sent a public letter to Eamon de Valera, President of Sinn Féin’s Irish Republic, inviting him to talks in London, along with Northern premier James Craig, it was de facto acknowledging Sinn Féin’s moral right to speak, not just for their party, but for southern Ireland as a whole.

With Northern Ireland’s Parliament established on June 22, 1921, Lloyd George could hold talks with the separatists without alarming his Conservative coalition partners unduly, assuring them that ‘Ulster’ would not be ‘coerced’.

Contrary, moreover to what police and military chiefs, Tudor and Macready had promised Lloyd George back in December 1920, the IRA guerrillas had not been defeated. Though some 6,000 republicans were imprisoned and around 500 dead, Crown forces’ casualties were still rising, not falling by the summer of 1921. Indeed, Nevil Macready, the military Commander in Chief in Ireland, was now advising the cabinet that victory could not be achieved without much more drastic measures and urged negotiation instead.

So it was that, to the great chagrin of many British military figures, General Macready negotiated a formal end to hostilities with the ‘Irish Army’, effectively dignifying a group that most had derided as a cowardly ‘murder gang’ prior to this, with the status of belligerents. IRA liaison officers were appointed around the country to meet with British officers to monitor the Truce, including wanted ‘murderers’ such as Cork IRA officer Tom Barry.

Talks with Sinn Féin would be on the basis, not of Home Rule – or limited autonomy within the United Kingdom – for southern Ireland but of ‘Dominion status’ that is along the lines of self government exercised by Canada and Australia. Partition was probably inevitable by this point, but the final shape of it was still up for grabs. All were well aware that nationalists were a majority in much of the south and west of Northern Ireland and indeed controlled many of the local government bodies there.

This basis for negotiations, which went on to be the basis of the Anglo-Treaty, had been mapped out well in advance by those advocates of conciliation on the British side, notably the leading civil servants in Dublin Castle; John Anderson, Mark Sturgis and Andy Cope. Hence the head of the civil service Warren Fisher’s remark on the Truce, ‘better late than never, but I can’t get out of my mind the unnecessary number of graves’.

In short, the Truce did mark, not just an end to violence, but an important sea-change in British policy towards the Irish independence movement.

Reactions to the Truce

Without a doubt, the response of the general population to the end of hostilities; that is to a lull in ambushes, killings, curfews, house-burning and reprisals, was relief.

This was the reaction of most IRA guerrillas also. Even though many, especially anti-Treaty Volunteers, would later paint the Truce as a mistake, the beginning of the road, as they saw it towards ignominious surrender of the Republican ideal in the Treaty, at the time, most were relieved.

The Truce meant that men who had been on the run for over a year, could emerge from hiding without fear of imprisonment or death, it also meant, in the following months, an influx of new Volunteers into the guerrilla organisation that, as Ernie O’Malley remarked, ‘was in danger of becoming popular’.

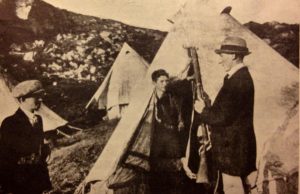

Public training camps were set up around the country in the autumn and winter of 1921. Inevitably perhaps, IRA discipline suffered under such circumstances and their Chief of Staff, Richard Mulcahy was particularly concerned about IRA units collecting what amounted to a mandatory tax or ‘contribution’ to IRA funds from the civilian population.

The Truce also meant that the Dáil Courts, set up by the Republicans, which had been driven underground during hostilities, could now re-emerge. These and their enforcers, the Irish Republican Police, were however still subject to arrest and prosecution in late 1921 for wrongful arrest and holding illegal courts by the Royal Irish Constabulary – a sign that the RIC had still not foreseen its disbandment under the terms of the Treaty, even at this late stage.

And finally the Truce was not an end to violence. Of the 2,300 fatalities counted by the Dead of the Irish Revolution project between 1919 and 1921, nearly 150 lost their lives between July 12 and December 31 1921. Most of these were in the North and 100 were in Belfast alone, where, as IRA officer Roger McCorley remarked, ‘the Truce lasted six hours only’.

The Truce is, in this sense a southern-centred landmark, it significance uneven in an all-Ireland context.