Book Review: Antrim – The Irish Revolution, 1912-23

By Brian Feeney

By Brian Feeney

Published by Four Courts Press 2021

Reviewer: Kieran Glennon

Before it was even published, this book had re-defined boundaries. Brian Feeney was one of the speakers at a January 2020 conference on “Writing the Irish Revolution: counties in perspective” and at that stage, this book was described as “forthcoming”. With numerous false dawns and postponements, some no doubt Covid-induced, that “forthcoming” then stretched beyond eighteen months. The good news is that – with a few caveats – it was worth the wait.

This is the Antrim instalment of Four Courts Press’ series of county-based studies of the Decade of Centenaries. Series editors Mary Ann Lyons and Daithí Ó Corráin have established a template for each book to follow: to look not just at republican separatism, but also at the home rule movement and unionism, as well as labour and feminist activism.

This is the Antrim instalment of Four Courts Press’ series of county-based studies of the Decade of Centenaries

Given that, during this decade, Antrim was simultaneously one of the last bastions of the old Irish Party, the principal strongpoint of unionism and the setting for almost 500 deaths during the Belfast pogrom, this book had arguably the most subject matter to cover. All this was supposed to be done within the constraints of 80,000 words.

When this reviewer asked Brian Feeney at the conference how he had covered so many themes in so few words, he cheerfully admitted that he hadn’t – at the time, the implication taken was that he had ignored the word-count. But judging by this slim volume of 149 pages, it appears some of the intended material wasn’t covered in as much depth as others.

Omissions

Feeney subsumes any analysis of women’s independent political activity into illustrations of their participation in the “bigger” unionist and republican movements.

So, for example, he contrasts the largest women’s political organisation in Ireland, the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council and its 115,000 members concentrated in the north-east, with Cumann na mBan which, at the time of the Easter Rising, had a mere 30 members in Belfast.

As regards labour activism, January 1919 saw the beginning of a general strike in Belfast’s engineering industry which lasted twice as long as the more widely-discussed Limerick Soviet of April 1919 and which, by temporarily denting the unionist near-monolith in Belfast, arguably had as significant an impact.

Women’s and labour activism could have been given more attention, especially as Labour was significant force in northern elections.

But just like his handling of the women’s politics part of his remit, Feeney’s treatment of the ramifications of this critical juncture in labour politics is almost non-existent – the strike comes and goes in a single page. Similarly, the significance of Labour’s performance in the 1920 election to Belfast Corporation, when it won more seats than Sinn Féin and the Nationalist Party combined, is not mentioned.

The chapter on unionism before the Great War is a fairly standard review of the home rule crisis, encompassing the development of the Ulster Unionist Council and the efforts of Edward Carson and James Craig, both at Westminster and in Belfast, to thwart the application of home rule to all or some of Ulster. Armed resistance was to be a central plank of their campaign, thus leading to the establishment of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Larne gun-running operation of April 1914.

This is all well-travelled territory although, in a single vignette, Feeney brilliantly illustrates the cosy nexus between imperial and unionist elites in this period: “Brigadier-General Lord Edward Gleichen, officer commanding British troops in Belfast from 1911, and a grand-nephew of Queen Victoria, played bridge at Craigavon [one of Craig’s five residences] with Craig’s wife as partner.”

Following the chapter on unionism is one half as long which reviews nationalism prior to 1914. Although Antrim saw the birth of the United Irishmen and their failed 1798 rebellion, led by Presbyterians, Feeney quickly establishes that in the 1910s, radical nationalism had limited appeal in the county: “Given the political and religious complexion of Antrim as a whole, and Belfast in particular, republicanism was a tender plant at the beginning of the twentieth century. As a political presence, it was invisible.”

But having thus dismissed the contemporary relevance of republicanism, after a swift potted biography of Joe Devlin, the Irish Party’s sole MP from Belfast or Antrim, the chapter then concentrates on the early development of the Irish Volunteers and Na Fianna, culminating in the split in the movement at the outbreak of the Great War. As Devlinite Hibernianism still represented the main pole of attraction within Belfast nationalism, one would have expected the balance of coverage here to be different.

One of Feeney’s recurring themes throughout the book is the inability of armed republicans in Belfast or Antrim to influence events. This is probably exemplified by his description of Belfast’s participation in the Easter Rising. A mere 132 Belfast Volunteers mobilised in Coalisland in Tyrone with the intention of marching to Galway, under strict orders that “not a shot was to be fired in Ulster” – their chances of achieving this no doubt improved by the fact that they only had 40 rifles between them.

The books shows how opposition to conscription in 1918 temporarily united all shades of political opinion, including unionists, as farmers from both sides of the political divide

They were accompanied by six women from Cumann na mBan, including two daughters of James Connolly; following the chaos engendered by Eoin Mac Neill’s countermanding order, the men returned to Belfast while the women made their way to Dublin.

Having a chapter entitled “Belfast and Antrim 1917-20: unionist redoubt” is perhaps a sideways reference to the Schwaben Redoubt briefly captured by the 36th Ulster Division at the Battle of the Somme.

While opposition to the proposed introduction of conscription was led elsewhere in Ireland by Sinn Féin, in rural Antrim it united all shades of political opinion, including unionists, as farmers from both sides of the political divide had a shared economic interest in continuing to supply food to the men in the trenches, in preference to supplying men to fight in those trenches.

Thus, Ballycastle witnessed the unlikely spectacle of an anti-conscription procession in April 1918 led by the flute band of the local Orange lodge.

In Belfast, the battle-lines were drawn differently. The December 1918 General Election saw a violent contest between supporters of Joe Devlin and Éamon de Valera in Belfast West: in the event, Sinn Féin was routed, both on the streets and at the ballot box. However, to state, as Feeney does, that “almost no-one in west Belfast had the slightest idea who de Valera was” is surely over-egging the cake.

Away from electoral struggles, the IRA set about re-building its organisation in Belfast – based first on GAA clubs, then later on parishes – and establishing some rudimentary structure in Antrim. Once more, Feeney is critical of their efforts:

“There was no one in Belfast with the clout to suggest that the IRA leadership should cut their suit to match their cloth … As a result, there were always more chiefs than Indians in the Belfast IRA.”

Pogrom

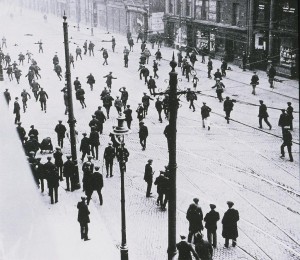

The final two-thirds of the book focus on the events of the last two years of the decade under review, beginning with the shipyard expulsions of July 1920.

This apparent imbalance is actually welcome, as it was those bloody events, above all, that defined the uniqueness of Belfast compared to the rest of the island.

Feeney has interesting observations about the authorities’ attitude to what he describes as “a paroxysm of murder and mayhem … unleashed on Belfast’s Catholic population in July.” Unionists distrusted the RIC’s largely Catholic rank and file and the police station in Glenravel Street was dubbed “the Fenian barracks.”

It can be assumed that unionists placed rather more trust in the RIC Divisional Commissioner appointed in November 1919: Brigadier-General Sir George Hacket Pain had been chief of staff of the pre-war UVF and a key organiser of the Larne gun-running.

Feeney describes the violence in Belfast as ‘a paroxysm of murder and mayhem … unleashed on Belfast’s Catholic population in July’.

The riots in Belfast in the aftermath of the IRA’s killing of District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn were used by unionists to support their demands to Downing Street for special constables, but Feeney is forthright in his assessment: “The claim that the north-east was about to be over run by the IRA and needed armed reinforcements from the unionist population was entirely spurious.”

That is not to say that Feeney is a mere republican cheerleader, far from it – he is withering in relation to their initial efforts: “Their activities were marked by incompetence, poor planning, faulty intelligence and demonstrated the lack of capacity of the Belfast IRA.”

Feeney’s portrayal of those activities follows much of the ground and covers many of the events described in Jim McDermott’s seminal Northern Divisions, although Feeney has the advantage of being able to draw heavily on the accounts given by key participants to the Bureau of Military History, as well as files from the Military Service Pensions Collection.

He describes how the IRA, although hampered by a lack of arms, improved their organisation in order to defend west Belfast nationalists, while illustrating the tensions in the early days between aggressive figures who wanted more offensive operations as “an integral part of the national struggle” and the more cautious Brigade Staff, who were wary of the ensuing reprisals which would inevitably be visited upon the nationalist population.

He is also critical of the IRA in Belfast and their ‘incompetence, poor planning, faulty intelligence’

At times, Feeney’s prose can be wonderfully acerbic: thus, the despatch of some of the Belfast IRA’s key volunteers to establish a flying column in Cavan is labelled a “hare-brained excursion”, while his description of Mary Fitzpatrick, leader of Cumann na mBan in north Antrim, is simply priceless: “Like other Cumann na mBan women, she carried despatches and smuggled weapons. She had a bicycle, which must have helped a lot.”

However, this second quotation also illustrates the fact that Feeney avoids the temptation to focus solely on Belfast at the expense of the wider county. A separate chapter reviews the IRA’s campaign – such as it was – in Antrim up to the Truce. Their main weaknesses were chronic shortages of both weapons and manpower – by July 1921, none of the Antrim Brigade’s four battalions had even a hundred members. A succession of Brigade O/Cs had to be imported from Belfast, one of whom was this reviewer’s grandfather: he gets off relatively lightly, with Feeney merely wondering about his tactical judgement.

1921 saw the first election to the new Parliament of Northern Ireland. Feeney devotes some time to analysing the Sinn Féin/Nationalist pact and their respective votes, but the most salient point was that Unionists won 40 of the 52 seats:

“They had demonstrated the political and electoral separateness of the six counties that they had been given to govern … They had control of law and order, had political control of their own heavily armed USC [Ulster Special Constabulary], and they were backed to the hilt by the British government.”

Republicans

Feeney is extremely critical of the national republican leadership throughout the book. In relation to the election, “When senior SF figures from the north went to Dublin for advice about how to respond to the election in the north, it was clear that the fight for the republic was the priority and, as usual, the plight of northern nationalists was not on the agenda.”

Covering the Truce and the violence that preceded it in Belfast, he says:

“If ever there was disconnect between IRA GHQ and the north … it was the timing of the truce. No one in Dublin had paused for a second to consider the effect on both nationalists and unionists in Belfast, in particular, of declaring a Truce on the eve of the Twelfth of July, of all days in the year.”

For unionists, no sooner had they gained the prize than the Truce appeared to snatch it away from them: the Specials were demobilised and the transfer of powers from Dublin Castle to Craig’s government was halted. Worse, the IRA was legitimised as an equal partner in relation to Truce liaison and began openly running training camps in Antrim.

Feeney is scathing of Michael Collins’ northern policy after the Treaty; ‘almost without exception, he made matters worse’ for northern nationalists.

Meanwhile, on the streets of Belfast, the Truce was ignored and Feeney catalogues the waves of violence that erupted in the city during the second half of 1921. The appearance of various unionist paramilitaries – some new, some revived – prompted the British government to return control of law and order to the Unionist government a couple of weeks before the signing of the Treaty.

Feeney is especially scathing on Michael Collins who, after the signing of the Treaty,

“[Collins] held the fate of nationalist inhabitants in the north-east of the country in his hands. Almost without exception, he made matters worse for them … Each of his approaches proved disastrous in greater or lesser degrees for Belfast Catholics in general, but also for the IRA’s 3rd Northern Division, in particular.”

The most significant of Collins’ interventions in the North – or more accurately, his ultimate disengagement from the North – was in relation to the northern offensive of May 1922, a plan devised in conjunction with his anti-Treaty opponents, aimed at destabilising the Unionist government. Feeney details the escalating sectarian savagery in Belfast during the spring of 1922, which formed the background to the plan being put together. He (accurately) summarises the offensive as a dismal failure for the 3rd Northern Division:

“Its concerted attack from 19 May, combined with shootings of USC members and extensive fire-bombing of unionist businesses and mansions, provoked a frenzied response from Craig’s government which unleashed the full strength of the USC in Belfast, a city which now descended into anarchy…”

Conclusion

From there, the book gallops to a conclusion, though bizarrely without an actual Conclusions chapter. Having surveyed the casualties, Feeney then weighs into the ongoing “Was it a pogrom?” debate.

Citing Irish News reports from as early as September 1920 and a Devlin speech at Westminster the following month, he observes that the term was “the common contemporary description, and as such must be respected.”

This reviewer would concur, but would have rather less patience for Feeney then trying to beat the full-back twice by going on to reference definitions of “pogrom” developed since the Second World War and as recently as 2003: surely a backwards reading of history?

The closing paragraph is as close as Feeney comes to a summary, but it is apt:

“The Irish Revolution in the north-east, best exemplified by events in Belfast, was not the overthrow of British government but the substitution of national control from Dublin by the re-imposition of British state power in that part of Ireland in the shape of a Belfast client administration run exclusively by Ulster Unionists.”

With one quibble – that “counter-revolution” would be a more accurate term – perhaps this overview is so concentrated that any further commentary would have been superfluous.

Feeney has provided a lively, extremely readable introduction to the period: while firmly grounded in the events that unfolded in Belfast and Antrim,

The main weaknesses of the book lie in what is not included: more in-depth studies of women’s and labour activism and Devlin’s constitutional nationalism plus, as noted, a knitting together of some conclusions.

In terms of what is included, Feeney has provided a lively, extremely readable introduction to the period: while firmly grounded in the events that unfolded in Belfast and Antrim, he is not afraid to let his irritation with all the main protagonists shine through, but he does provide evidence for his judgements.

Although constrained in terms of length, the book should provide a valuable prompt for readers to go on to explore the subject further in other, more extensive and detailed works. Feeney’s main contribution is that he illustrates clearly how and why the outcome of the revolution in Antrim diverged so dramatically from that in the majority of the other counties covered in this series.

Kieran Glennon is the author of From Pogrom to Civil War: Tom Glennon and the Belfast IRA