The Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stone Layers: from medieval times to Irish independence

By John Dorney

One of the oldest, if not the oldest trade unions in Ireland is the bricklayers’ trade union the Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stone Layers, which dates back to 1670.

The story of the modern union encompasses many of the great events of early 20th century working class life in Dublin: strikes, unemployment, disease, death and also national events such as the Lockout of 1913, the Rising of 1916 and the subsequent struggle for Irish independence.

However the story of the union and the guild that preceded it is much older than this, dating back centuries. For its origins we must look back further still to the guilds of medieval Dublin.

In this way the story of the bricklayers’ union is also part of the evolution of workingmen’s organisation and politics in the city of Dublin over several centuries.

The Guilds of Dublin

The Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stone Layers (AGIBS) traces its foundation all the way back to 1670 when it was founded as the Guild of Saint Bartholomew. [1]

A guild differed in many ways from a modern trade union. First of all the guild had a monopoly on who, and how many, young men were allowed into the trade as apprentices. The guild was responsible for training apprentices and also for enforcing standards in the trade.

The guilds of Dublin dated back to the Guild Merchant founded in the 12th century, not long after the Anglo-Norman conquest, with its head office on Winetavern street with a side chapel in Christ Church. By 1498 there were 17 guilds, representing various crafts, the tailors having been the first to break free of Guild Merchant and found their own organisation.

The medieval guilds were far more than trade organisations, they had a social and religious function also – each guild having its own patron saint and chapel. All paraded under their guild banners at religious holidays such as Corpus Christi, Shrove Tuesday and St George’s Day, behind the Lord Mayor, before retiring to their own banquets and festivities. In the middle ages, they even played a military role. Guilds played some role in citizens’ militia which helped to defend the city. [2]

As late as 1785 the Dublin guilds would still parade with the lord mayor around the city limits ending with a ‘sham battle’ at the Combe. But by 1785 this parade was becoming increasingly disorderly and the final one in that year ended with rioting including military intervention and three deaths, leading to its discontinuance. [3]

Secondly the guilds had a special place in the politics of the city of Dublin. From the 15th century they had become a part of the city government and after a serious riot by guild members in 1759, secured free election of their candidates to the lower house of the city’s government.[4]

A full guild member was also a freeman of the city and entitled to vote in the municipal elections to elect Aldermen to the Corporation. This was restricted to Protestants following the victory of William of Orange over King James and the Jacobites in 1692, meaning, among other things, that the city government of Dublin was dominated by Protestants until 1840. Though Catholics were re-admitted to the guilds in 1793, most remained majority Protestant.

Over time, the political function of the guild became more important than the economic, as trade grew less regulated and ‘journeyman associations’ overtook the guilds as representatives of Dublin’s artisans. By late 18th century journeymen combinations had replaced guilds as the main representative body of Dublin workers. Usually they met in public houses. Some, such as the tailors could date their foundation back to the 1670s but most dated back to the 1720s. Despite ‘anti-combination acts’ the journeymen’s associations grew from 1750s onwards, especially in the building trades, the journeymen’s ‘combinations’ grew far more numerous than the old guilds.

The Carpenters’ society, for instance founded 1761 had 1,900 members. The famous architect James Gandon noted with dismay that ‘fellows called orators…keep up a perpetual ferment… rendering men dissatisfied with their employers’. The associations had an oath, list of membership and membership fees. Despite a new ‘combination act’ in 1780 strikes became increasingly common in the 1790s.[5] With respect to bricklayers, the ‘combination’ concerned was founded in 1792, as the Old Bodymen and in 1802, became the Regular Operative Brick and Stonelayers.

St Bartholemew’s Guild or The Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stone Layers

St Bartholemew’s Guild of stone and bricklayers itself dated back to 1670, when bricklayers and plasterers broke away from the carpenters’ guild. Membership of the guild was hereditary, and so passed down through the generations, despite the fact that by the late 18th century, the majority of its members were no longer stone or bricklayers.

The guilds’ voting power in Dublin, , was brought to an end in 1840 when Thomas Drummond, the Liberal Chief Secretary for Ireland, reformed the Corporation so that voting rights were extended to all male property holders. The guilds of Dublin were also formally abolished in 1846.

However the Bricklayers’ guild survived by transforming itself into what was known as a craft union – probably combining the old guild with a journeyman’s association. The craft union was close to the old model of a guild but without the political functions. The union was formally re-founded in 1888 as the Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stone Layers with its headquarters at 49 Cuffe Street in Dublin’s south inner city.

The union still tried to limit entry into the bricklaying trade in Dublin (apart from a branch in Kingstown, now Dun Laoghaire, it was confined to the city) and its members refused to work alongside ‘colts’ or non-union members. The intention here was to keep the wages of bricklayers high by limiting the number of trained bricklayers available at any one time.

The union provided benefits for members including sickness benefit(for up to six months and unemployment benefit, but only from December until March, which were the quiet months for the building trade. From 1911, the union also administered the National Pensions for its members. The union also provided a free library for members in its Hall on Cuffe Street and had its own marching band.

There was also a mortality benefit to cover funeral costs. So long as a union member was ‘fair’ (i.e. his dues were up to date) he was entitled to a mortality benefit of £10 for himself in the event of his death (reduced to £8 following the union’s disastrous defeat in the lockout of 1905, see below), £7 for his first wife, £3.12 for his second wife and £2 for children.

In theory, this meant that a skilled bricklayers was considerably better provided for than one of Dublin’s burgeoning unskilled labourers. In Dublin it was common to make a distinction between the old craft unionist, such as the bricklayers and the new ‘general unions’ such as the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union founded by James Larkin, which represented unskilled labour.

However, as John Hogan the historian of the AGIBS, notes, although the bricklayers liked to portray themselves as an ancient guild and an ‘aristocracy of labour’ in fact, most had little to no surplus income;

As few members of the union ever appeared to have much money in life, this benefit guaranteed them that at least they would have dignity in death. The money provided was usually sufficient to pay the expenses of the funeral, as in many cases members could not afford these costs. This situation in a way gives lie to the image that the trade tried to portray of itself, with its pomp and circumstance. In reality few members … could have been considered in any way affluent. Most lived lives of varying degrees of hardship, mortality benefits helping in some small way to alleviate their adversities.

Strikes

The bricklayers’ union engaged in prolonged strikes in 1905, 1913-14 and 1920. These were the great set piece battles that the AGIBS fought against employers in the early 20th century.

From the 1880s onwards the AGIBS had grown in confidence, winning a number of disputes, resulting in higher pay and also tighter control of the union over the employment of non-union brick and stone layers.

However in 1905 they over-reached themselves and got involved in a disastrous dispute in which most of their membership in Dublin was ‘locked out’. The dispute arose over a resolution passed by the union allowing their members to do work for private companies outside the Master Builders’ association.

The Master Builders objected, as this would have broken their control over the building trade in Dublin, and threatened to lock out the AGIBS membership unless they rescinded the resolution. They duly did lock out the union membership on February 28 1905. They would remain out of work until July of that year, in which time the union spent over £1,500 on strike pay, almost bankrupting itself before going back to work on the Master Builder’s terms and with reduced pay.

The defeat of 1905 caused a great deal of hardship to their members. Richard O’Carroll, an energetic young organiser took over after the leadership of the union from the older Michael Ennis and managed to save the union from financial extinction. However, for a time many benefits had to be cut, including mortality and sickness benefit and pensions.

In 1913 Richard O’Carroll was one of Jim Larkin’s main allies during the great Lockout of that year, in which up to 20,000 workers were ‘locked out’ by a coalition of employers because they would not sign a pledge not join Larkin’s ITGWU or ‘associate’ with any members of it. In this way, the bricklayers’ union had aligned itself with the ‘new unionism’, shedding the previous distinction between the guild-like craft unions and the new ‘general unions’.

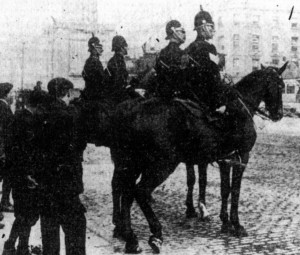

The lockout was famously violent, with strikers attempting by force to halt business in the city and police attacking workers’ demonstrations. On August 31, 1913, the Bricklayers’ general secretary, Richard O’Carroll was beaten up by Dublin Metropolitan Police on ‘labour’s bloody Sunday’ after addressing a workers’ rally in Inchicore.[6]

By November 1913, Bricklayers Union had 520 members affected by lockout – locked out for refusing to sign a pledge not to work with ITGWU members. They received £1,606 9 shillings from the strike fund collected by Dublin Trades Council. Mostly thee were donations from British unions. They were paying out £128 a week and collecting only £10 that month.[7]

The Bricklayers went grudgingly back to work in early 1914, much as most Dublin workers did, hunger and lack of funds forcing them back to work on the employers’ terms.

The AGIBS last great strike of the period was in September 1920, in which the bricklayers and other building workers in Dublin went on strike for a pay increase. This time the union had learned the lessons of the 1905 and 1913 disputes and managed to avoid its strike funds being exhausted by sending members to work in England for the duration of the dispute. Bricklayers who went to work in England had to send back 2 shillings 6 d to the strike fund.

In April 1921, the employers, the largest of whom was actually Dublin Corporations housing commission, climbed down and acceded to the demands of the workers, who went back to work with a substantial pay rise.

However they were again on strike in 1922 when the Corporation tried to lower wages.

Nationalism

The politics of guilds in Dublin were complex over the centuries. In 1759 the guilds had rioted when it was threatened that then Irish parliament on College Green in Dublin would be abolished. However, by the 1790s the guilds, as opposed to the journeymen’s associations, had become strongholds of Protestant ‘reaction’ against reform and revolution.

In 1799, seventeen out of twenty-five Dublin guilds came out against the Act of Union that finally did abolish the Irish Parliament. But many did so on the grounds that the Union might threaten Protestant domination over politics and trade in Ireland. [8]

The nineteenth century craft unions, that followed and in some cases emerged out of the guilds, however, were considerably more Catholic in their membership and more unambiguously nationalist in their politics.

According to labour historian John Hogan, the AGIBS was from an early stage an Irish nationalist union. It marched in support of Daniel O’Connell’s Repeal movement in the 1830s, looking for Repeal of the Act of Union and the return of Irish self-government to Dublin, marched for an amnesty for Fenian prisoners in the aftermath of the 1867 rebellion, and its members were also prominent in the upheaval in pursuit of Irish independence from 1916 to 1923.

Richard O’Carroll the general secretary of the union, was a member of Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Irish Volunteers. He fought at Jacobs Biscuit factory in the Easter Rising and was captured by British troops on the first day of the Rising. After capture he was gunned down by Captain Bowen Colthurst, who later also killed the pacifist Francis Sheehy Skeffington and a number of other innocent bystanders in Portobello barracks.

In 1918 the AGIBS participated in the Irish Trade Union Congress’s general strike against the British government’s attempt to extend conscription to Ireland, with all members downing tools as part of a nationwide strike on April 23. The strike was decisive in defeating the attempt to impose conscription.

Christopher Byrne of IRA Dublin Brigade 4th battalion recorded that the Republican Court in the south inner city (underground courts that aimed to by-pass the British courts) was held in the Bricklayers Hall on Cuffe Street. [9]

In April 1920, again the AGIBS participated again in a general strike, this time for three days, for the release of Republican prisoners who were on hunger strike. The prisoners were released. Hogan comments that this shows the nationalism of the AGIBS rank and file.

The Bricklayers’ union today

In 1988, the AGIBS amalgamated with the National Union of Woodworkers and Woodcutting Machinists to form Building and Allied Trades Union or BATU and moved out of their HQ at Cuffe Street.

Cuffe street itself is today unrecognisable having been dramatically widened in the 1990s.

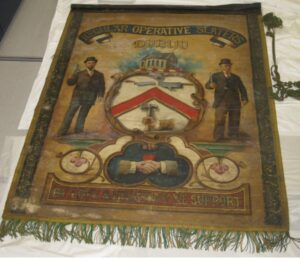

Batu have their headquarters at Arus Hibernia, Blessington St, Inns Quay, Dublin. The records of the old guild are held in the National Archives of Ireland. They still hold the original guild banner of St Bartholomew, which can be viewed here.

If you enjoy the Irish Story and wish to support our work, please considering contributing at our Patreon page here.

References

[1] All references to the history of the bricklayers’s union are, unless otherwise stated, from John Hogan, From Guild to Union: The Ancient Guild of Incorporated Brick and Stone Layers in pre-Independence Ireland. http://doras.dcu.ie/19556/1/John_W_Hogan_20130930140824.pdf

[2] David Dickson, Dublin the Making of Capital city (Kindle version 2022), pp, 22, 27, 29, 35

[3] Dickson, Dublin p.232

[4] Ibid, p175

[5] Dickson, p.242-243

[6] Padraig Yeates Lockout, p.74

[7] Yeates, Lockout p.327

[8] Dickson, Dublin, pp,175, 238, 262

[9] Christopher Byrne BMH statement here).