Book Review: The Celts, A Sceptical History

By Simon Jenkins

By Simon Jenkins

Profile Books Ltd, 2022

Reviewer: Patrick Fresne

The word ‘Celt’ is a potent attention-grabber in the English-speaking world, and for publishers in particular, the word seems to have long served as a kind of literary clickbait, as becomes particularly evident during the festive season. Most years, and in most bookshops, it seems at least one new release featuring the evocative word in the title appears on the shelves, with such works typically being elevated into positions of prominence in bookstore displays at the approach of Yuletide.

This year, the latest offering falling into this paradigm is of a leerier bent than most. In The Celts: A Sceptical History, the newspaper columnist and prolific author Simon Jenkins has turned the lens of his attention to a topic close to home, or at least, to that of his Welsh forebears, his father’s side of the family hailing from Merthyr Tydfil in the south of Wales.

In The Celts: A Sceptical History, the newspaper columnist and prolific author Simon Jenkins offers an overview of the story of the Celts, questioning the validity of this term.

Panoramic in scope, the work offers an overview of the story of the Celts, predominantly within a British and Irish context, with the author’s particular preoccupation being the controversy around this curious and most ancient umbrella term, ultimately harking back to the early Greek word Keltoi, which was employed by early Classical writers to denote a cultural grouping whose homeland was located somewhere to the west of Greece (variously identified as southern France, the mouth of the Danube or in Europe’s western fringes).

In modern times, the term is commonly used in reference to the family of languages that are currently spoken in regions on Europe’s western fringe, but the word today finds usage in a potpourri of contexts, including within the fields of art, music and even sport.

In naming the work, Jenkins lays his cards on the table. But by declaring his uncompromising view of the subject from the outset, Jenkins has opted to walk a perilous tight-rope. The invariable risk here is that evidence might end up being shunted into routes that suit the author’s predetermined narrative, and this bogey never lurks too far below the surface throughout this work.

While some researchers go to great lengths to painstakingly reference their work, and still struggle in vain to find a publisher, Jenkins, whose work is entirely devoid of references, seems to have faced no such hurdle, the authors’ prominence in the media (Jenkins has written for extensively for the Times and the Guardian) presumably helping to smooth the path to publication.

Lack of academic rigour notwithstanding, the work has garnered widespread attention over the course of this year, being reviewed by panoply of mastheads across the United Kingdom as well as the Irish Times,[1] and the author’s arguments being showcased in a feature piece in The New Statesman earlier this year.[2]

***

The term ‘Celtic’ has a propensity to rankle, and not without some good reason. The term is amorphous, meaning different things to different people. The fact that the term is often thrown around haphazardly and lazily doesn’t add much to the credibility of the vague ethno-cultural label.

For this reason, over recent decades historians have thus tended to shy away from the term.

The ‘Celtosceptic’ sentiments evident in the Jenkins work largely find their inception in debates within the field of Celtic Studies in the 1990s, and especially associated with the British academic Simon James, whose 1999 work The Atlantic Celts represented a throwing down of the gauntlet to a widely accepted view of the Celts.

This nub of his argument is that there is no primary evidence that the term ‘Celt’ was applied to the people of Britain or Ireland in ancient times, and that the notion of ancient Celts in Britain or Ireland is essentially a modern invention, the ‘Celtic’ cultural-badge emerging in these lands only in the 18th century.

This nub of his argument is that there is no primary evidence that the term ‘Celt’ was applied to the people of Britain or Ireland in ancient times, and that the notion of ancient Celts in Britain or Ireland is essentially a modern invention

This line of argument has not gone unchallenged, the debate remaining unsettled.

Ten years ago, the archaeologist J.P Mallory made a pointed observation about the inconsistency with the Celto-Sceptic line of argument, observing that the term for the language and culture known as Germanic presents even more problems: the word originates with the ancient tribe of the Germani, a name which was probably of Celtic provenance, and who may have actually been Celts.[3]

And yet, as Mallory observed, the debate around the question of Germanic has never seemed to ignite as much rancour, or even as much interest, as the question around ‘Celticity’ does.

At any cost, the ‘Celtic question’ remains unresolved, though this is not an impression that a casual reader would form after reading Jenkins’ work.

****

While the absence of references invariably strains the credulity of Jenkins’ arguments, key arguments advanced by the author are also problematic, often failing to straddle the logical hurdle.

The problems become apparent early on. The author’s novel suggestion, in the third Chapter of the work, that parts of south-east of England had been populated by Anglo-Saxons since pre-Roman times is bound to leave an informed, sober reader rubbing their eyes, wondering if they just imagined what they had just read.

As if to clear up any lingering doubts, Jenkins then goes on to repeat the claim only a couple of chapters on, closing the chapter by mooting the question ‘Why do the English not speak Welsh’ to which, he surprisingly concludes, ‘The answer must be because they speak English and always have’.

Jenkins’ biases shine through here. Unfortunately, the nationalist strain that is on display in the above passage also seems to colour some of his commentary on the Irish language in subsequent chapters.

Jenkins attempts to argue that the inhabitants of what is now England always spoke a form of English, a highly questionable idea.

The author has been widely -and rightfully- panned for his lackadaisical view of the Irish language, which Jenkins declares to be ‘impenetrable‘ and describes as a ‘difficult tongue’.

This chauvinistic assessment is nonsense, and myopic to boot, considering that English is far from the easiest of languages to master, as countless aspirational migrants to English speaking countries have found over recent decades.

Despite his blinkered view of the language, his coverage of Irish history is generally dispassionate, even if his knowledge of Irish history is also often patchy. Owen Roe O’Neill, for example, was not a leading figure in the 1641 Irish uprising, as is stated in the work. O’Neill only arrived in Ireland in July of 1642, long after the initial outbreak of hostilities.

Also questionable is Jenkins’ argument that Irish nationalism in the late 19th century ‘had nothing to do with Celts’, the desire for Home Rule being the sole driver.

This assessment is at best an oversimplification. There were certainly numerous Irish nationalists of this period who perceived the nationalist cause as being closely intertwined with Ireland’s ancient traditions. A case in point here is the writer James Stephens, best known today for his Irish Fairy Tales, a work still widely available today, despite the passage of the years.[4]

Stephens was fascinated by Irish folklore, with the lore of ancient Ireland being a dominant theme in much of his corpus. But as he wrote works inspired by the tales of old Ireland in the early years of the 20th century, Stephens was all the while active in the Sinn Féin movement, which had recently been founded by Arthur Griffith, and was also a close friend to Thomas MacDonagh, a commander during the 1916 uprising, and one of the fifteen leaders to be subsequently executed.[5]

Perhaps it is not entirely coincidental that Stephens best-known work, which related the mythological stories of ancient Ireland (or Irish Fairy Tales, as he called them) was published in 1920, in the thick of the Irish War of Independence, and only four years after the Easter Rising.

Most of the stories in Stephens’ work relate to the deeds of the Fianna warrior bands of ancient Ireland. That many other contemporaneous nationalists also saw the Irish struggle as being bound up in the legendary past of Ireland is evident by the fact that one notable political faction that emerged out of the tumult of the 1922-23 Civil War, De Valera’s Fianna Fail party, took on the name of the same ancient Irish warrior-band.

In naming the party thus, De Valera’s clear intention was to create the perception of a bridge between Ireland’s distant past and the contemporaneous political situation.

Of course, this begs the question as to whether the ancient Irish can be regarded as ‘Celts’. Still, it is not entirely implausible that a ‘Celtic connection’ might be buried within the very name of these ancient Fianna.

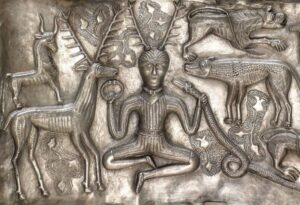

The word fianna equates to deer in Irish, an animal which is known to have had a potent symbolic and mythological significance to the ancient Celts. One such animal features prominently on one of the plates of the Ancient Celtic artefact known as the Gundestrup Cauldron, for example.

This represents just one example of numerous tantalising, if non-concrete, correlations between the European Celts and ancient Irish traditions, and highlights why many scholars who are familiar the subject matter remain unconvinced by the ‘Celto-sceptic’ line of argument.

***

The Celtosceptic arguments outlined in the work rely heavily on etymology and toponymics.

The lack of Celtic place names in much of England is cited by Jenkins as evidence of a limited Celtic presence within these regions. For example, the eastern side of Britain has only 35 Celtic-derived place names, compared to hundreds of Germanic origin in the same region.

And yet, it only takes the most cursory glance at the maps of other countries that fall within the Anglosphere to highlight the logical fallacy behind this reasoning: vast swathes of the territory of Australia and Canada are dominated by place names derived from English, and yet we know that English speakers are relatively recent arrivals in these lands.

Similarly, Jenkins second line of attack, focusing on the paucity of English-derived Celtic words as evidence for a lack of a Celtic presence in England, is equally fraught.

In their efforts to reconstruct words, the focus of etymologists tends to fall on textual sources. Given this, it is invariable that it is more common for words to be traced back to literate cultures, such as that of Rome, simply because solid evidence for their ancient usage can be observed ancient texts. By contrast, in ancient times the Celts were primarily an oral culture, and thus almost all written Celtic sources post-date Christianity.

In essence, it is more problematic to identify the Celtic lexicon of ancient times, in stark contrast to that of Latin or ancient Greek. But as any historian should be aware, an absence of evidence should not be taken as evidence of absence.

Jenkins also makes some effort to deploy the latest genetic evidence to bolster his cause , however his discussion of the subject seems muddled and overly simplistic, with the author problematically equating the lack of consistent genetic evidence of an ancient, pre-Roman invasion of Britain and Ireland as evidence for the absence of an ancient Celtic culture in the region. It is hard not to get the sense that the author is well out of his comfort zone here.

***

The publication of the work earlier this year was met with a predictably frosty reception, the work being panned in both the Irish Times and the Welsh Nation Cymru.

And yet, there are some positives. Jenkins’ pencraft, honed over decades, is evident here, and even the most disinterested reader won’t have too much difficulty working their way through the book. The author also seems to make a genuine effort to cover the ‘Irish angle’ of the subject of the work.

While some of the authors views are jaundiced, and his understanding of Irish history at times deficient, you at least don’t get any sense here that the Irish material has been ‘tacked on’ to a book that is really about Britain, a flaw which not all British writers of this type of panoramic endeavour have managed to evade.

While some of the authors views are jaundiced, and his understanding of Irish history at times deficient, you at least don’t get any sense here that the Irish material has been ‘tacked on’ to a book that is really about Britain

And while Jenkins’ views have been labelled as ‘British Propaganda’ in one review [6], this suggestion is perhaps overwrought. Jenkins, for example, is sympathetic to the plight of the Irish during the Great Famine, and doesn’t shy away from shining a spotlight on the bigoted attitudes in Britain that served to exacerbate the tragedy, highlighting Sir Charles Trevelyan’s attitudes in particular (‘…The judgement of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson….as a mendicant community..’ )

Indeed, had this had been intended as a broad overview of the Insular Celts intended for a general readership, Jenkins’ work might have served as a laudable contribution to popular understanding of the subject.

But in opting to take a simplistic and partisan stance on the knotty question of the Celts, Jenkins leads himself into a minefield of his own making.

His ultimate conclusion, ‘that there was no such tribe, country, culture or language’ that can be described as Celtic is inaccurate. There certainly were and are Celtic languages, and there is clearly a relationship between modern Celtic languages and those spoken in ancient times, as was noted by the Welsh academic Patrick Sims-Williams in a piece rebutting some of the arguments laid out in this work. [7]

And although the issue of culture is not so clear cut, the author’s simplistic arguments do not do justice to the complexity of the debate.

Unfortunately, by adopting a partisan slant on the controversy of the ‘Celtic Question’ from the outset, Jenkins impinges the integrity of the work, and effectively scuttles his own ship. This is in many ways unfortunate, because the ‘Celtic question’ is an important one, and it is a question mark that hovers over the isle of Ireland as much as it does Britain.

Ultimately, The Celts: A sceptical History, while lucidly written, is at heart a deeply flawed work, while highlighting important questions.

Hopefully, the publicity generated by the work will prompt others to step up and attempt to demystify this intriguing identity crisis.

Patrick Fresne is a researcher and a graduate of the University of Sydney, where he studied History and Celtic Studies.

.

[1] Berresford Ellis, P , 2022 , Celts used a mythological political whipping boys, The Irish Times, Accessed 20 December 2022 (View Link)

[2] Jenkins, S, 2022, It’s time to banish Britain’s Celtic ghosts, The New Statesman, Accessed 20 December 2022 (View Link)

[3] Mallory, J.P, 2013. The Origins of the Irish, Thames & Hudson, London, p 247

[5] Hughes, B, 2018, Featured Letter, Letters 1916-1923, Accessed 20 December 2022 (view link)

6 Sims-Williams, P , 2022 , Beyond the fringe, Times Literary Supplement, Accessed 20 December 2022 (view link)