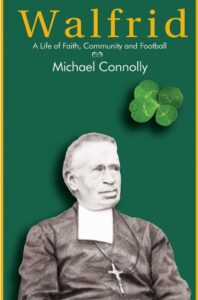

Book Review: Walfrid: A Life of Faith, Community and Football

By Dr Michael Connolly.

By Dr Michael Connolly.

Published by Argyle Books

Reviewer, Barry Sheppard

The connections between Glasgow Celtic Football Club and Ireland are well known, even to those who don’t follow the beautiful game. The green and white hooped shirts with a shamrock crest have become famous around the world and worn by many who make up the vast Irish diaspora. The fans’ weekly pageants of green and white and lengthy repertoire of Irish folk songs are public affirmations of an Irish cultural identity which has tied the club and its fans to Ireland for over 135 years.

Outside of its strong Irish bonds, the club was, from the outset also avowedly Catholic. For while many people from outside the Catholic faith have served the club with distinction since its formation, the early years of Celtic were an outworking of a proactive social Catholicism which had taken root in Glasgow in the latter decades of the nineteenth century.

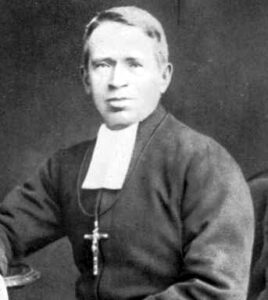

Famously Celtic F.C. was founded by Irishman, Brother Walfrid, born Andrew Kerins, in Glasgow in 1887

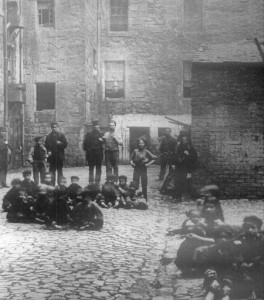

The initial meeting to form the club took place on 6th November 1887 in St. Mary’s Catholic Parish Hall in the Calton area of Glasgow’s East End. It was in this area of the heavily industrialised city that many thousands of Irish, mostly Catholic, immigrants had arrived. Fleeing famine and destitution, they mostly found precarious, unskilled, and dangerous work in the city’s flourishing industries.

Outside of dangerous, labourious daily toil, the city’s new arrivals found themselves crammed into substandard housing, where the unsanitary conditions allowed disease to flow freely, and the lack of funds allowed many to go hungry. Glasgow was far from the El Dorado that many hoped it would be.

The Second City of the Empire

The influx of Irish into Glasgow was, of course, part of a wider movement of people fleeing Ireland at the time of the great Irish famine of the 1840s.

During this period, the Irish-born population of England, Scotland and Wales rose considerably. In 1841 the Irish born population in Britain stood at 415,000. By 1851 it had rocketed to 727,000, before reaching 805,000 in 1861. This last figure constituted 3.5 per cent of the total population of Britain.

Despite large numbers, the Irish in Victorian Britain were often seen as alien, a people apart. Roger Swift has commented upon the Irish experience in Victorian urban Britain in this era as ‘an often harsh and disorientating’ life. Concentrated in towns and cities, the Irish, he notes ‘stood out from the host population by their poverty, nationality, race and religion’.[1]

It was the ‘othering’ of the Irish population in Glasgow that, in effect gave birth to the Celtic Football Club. While some of the Irish population in Glasgow had been there for a generation, sometimes two, by the time the club came into being, they still largely occupied the bottom run of the social ladder. The club’s charitable vision of aiding the poor Irish of Glasgow was a defining moment in the history of the city’s Irish community, and indeed something which set Celtic apart from most other clubs which came into being during that period.

It was the ‘othering’ of the Irish population in Glasgow that, in effect gave birth to the Celtic Football Club

Conversely, the charitable origins of Celtic and the fact that they were formed by exiled Irishmen in Glasgow has led to much mythologising and romanticisation. That vast repertoire of folk songs many Celtic fans are nurtured on, and some overly romantic popular histories of the club have helped form an often rosy, if in parts grim, picture of its history. Thankfully, this new publication Walfrid: A Life of Faith, Community and Football by Dr Michael Connolly does not travel down the romantic route.

It is astonishing, given Walfrid’s importance to the foundation and ongoing legacy of the club that this is the first biography written about his life. Based on Connolly’s PhD thesis, the book not only gives a fine account of Walfrid’s life, it also offers a fresh perspective on a variety of important social topics which contributed to the birth of the famous football club. Connolly tackles diverse themes such rural life, emigration, urban poverty, labour, religion, charity, integration, education, and sport with a great rhythm as he sketches out the life of his subject.

Brother Walfrid, born Andrew Kerins in 1840 in Ballymote, County Sligo, was the son of a small tenant farmer. Like many of his contemporaries, Kerins left Ireland at a young age to seek a new life. Aged fifteen, he journeyed to the ‘Second City of the Empire’ with a childhood friend. Landing in the large port city of Glasgow, Kerins found work in a variety of backbreaking jobs, including the regions developing railway system.

Brother Walfrid, born Andrew Kerins in 1840 in Ballymote, County Sligo, was the son of a small tenant farmer and worked in Glasgow before joining the Marist Order

After some time toiling in the industrial heartland of his new country, Kerins changed direction and decided to take religious vows. From industrial worker to a man of the cloth who founded a world-famous football club, it is, to be fair, a story which could quite easily be mythologised.

Connolly naturally begins by charting the early life of Walfrid in Sligo. Not always an easy task, given the dearth of records and sources from that famine and immediate post-famine period. Of course, the damage done to the public records at Dublin’s Four Courts in the Irish Civil War has hampered many historians over the years. Connolly compensates for this by engaging in a variety of alternative sources to construct a picture of Kerins early years, including Tithe Applotment records, and even the accounts given to the Irish National Folklore Collection. In engaging with these sources, Connolly manages to provide a sound base for his subject’s early life.

The author juxtaposes the quiet, if ruptured early life of his subject in rural Ireland with the chaotic noise of the industrial heartlands of Scotland in the mid-nineteenth century. In doing so, he is able to demonstrate the culture shock which Walfrid (and many others) experienced upon arriving on Scottish shores.

The author’s knowledge of the streets which Kerins lived and worked in adds an air of authority to the topic. Painting a picture of the city which successive generations of Irish migrants flocked to, the author does not shy away from the multitude of problems which were, sometimes deliberately, placed before them.

The sectarianism and anti-Irishness which this community faced is described in great detail, yet is not overplayed. Interestingly, the Irish community experience in this period is not solely defined by the sectarianism and prejudice which they had to confront. Connolly frames it as an important part of a wider Catholic revival in Scotland, which saw the first significant changes to the country’s religious makeup since the Reformation.

Transnational Catholicism

Kerins’ life and transition into Brother Walfrid is, of course, central to the book. Connolly’s account of the Catholic revival in Scotland which Walfrid was a part of is fascinating in itself. He shows that this important religious revival was not solely led by the sheer weight of numbers in Scotland’s Irish Catholic community, however.

This Catholic revival was, Connolly argues, ‘primarily facilitated through the work of Catholic charitable organisations, religious orders enlisted from Europe and the development of a distinct system of education’.[2]

While not explicitly labelling the Catholic revival in Scotland as transnational, the reader cannot help but grasp this vitally important point. Connolly’s work should be partly viewed as an important case study in nineteenth century Catholic transnationalism, which positioned community activism, education, and civic engagement as vital for the spread of moral ideas and community empowerment.

Kerins’ decision to join a religious order of French origin is vital in understanding the character of the man who became Brother Walfrid and the ideology behind the club he helped establish. Serving in an international religious order focused on education opened the young Irishman up to the wider world of transnational Catholicism. The Marist order he served was established in 1817, during a period of Catholic revival in France.

The order rapidly spread beyond France’s borders into to numerous countries, playing an important role in the internationalisation of Catholic education and social endeavour. Connolly rightly draws attention to this when demonstrating that the supposedly parochial, insular looking Irish Catholic community in Glasgow was nothing of the kind. Highly influenced by European religious thinking and social activism, Glasgow’s Catholic Irish were not an isolated community, they were part of a wider transnational world.

That is not to say that the Irish Catholic community in Glasgow were not socially and religiously isolated on a day-to-day basis. They often were. Connolly, however, offers us a fresh perspective on the moral and ideological underpinnings of that community under the leadership of Walfrid and his international cohort in the Marists as they took charge of the education of Glasgow’s Catholic youth.

Walfrid campaigned for Catholic education in Scotland.

The struggle for recognition of Catholic education in Scotland is one of the strong points of the middle chapters. The order battled for position in a country where the education system ‘by definition was Protestant in character’ and didn’t provide for religious instruction to those of the Catholic faith. Connolly argues that Catholics seeking to have their children instructed in their own faith had to, in effect, ‘pay twice’, once for the national school system and then for their own Catholic schools.[3] In a community where money was often scarce this was highly problematic.

The force of Walfrid’s personality was vital in securing piecemeal funds for Catholic education in the city. The Brother’s magnetic personality was a vital lifeline as he engaged with the great and the good in securing funds for poor children. Walfrid’s interpersonal skills were, of course, brought to bear later with the establishment of Celtic.

While Walfrid is the focus of the study, Connolly is quick to point out that he was no one man army. Assisted by others in the order in Glasgow, particularly Brother Dorotheus, Walfrid’s right hand, the Irishman became a central figure in the uplift of Glasgow’s Irish Catholic population.

Education was undoubtedly the central focus of Walfrid’s time in Glasgow. However, he was quite aware that getting children through the doors of the schools was less than straightforward. Economic necessity often kept children from the classroom. Aiding their hard-pressed parents in contributing to the family income often took precedence over education. And when children did make it to the classroom, hunger very often impeded their concentration and development. The inability of families to provide sufficient food for themselves, especially the children, soon became a focus of Walfrid’s mission.

The Formation of Celtic F.C.

In 1870 Walfrid was assigned to a teaching position in St. Mary’s Boys’ school in the Calton area of Glasgow’s East End. It was in this impoverished area where the idea for a football club to raise funds for the poor began to take shape.

Connolly shows that in the East End parish, the Marists introduced football as a means for the advancement of the children in their care. Walfrid, now in a senior position in the order, spearheaded many fundraising endeavours for the upkeep of teaching facilities and other projects for the education of the Catholic children in the area. Connected to this was the ongoing need for young scholars to be nourished properly.

Cletic F.C. was originally founded to ‘supply the East End Conferences of the Saint Vincent de Paul (SVDP) Society with the funds for the maintenance of the dinner tables of our needy children’.

It was during Walfrid’s time in the city that what was referred to as the ‘Penny Dinners’ scheme was introduced. This scheme, which provided poor Catholic children with food had the dual purpose of feeding hungry children and improving attendances at Marist schools. The scheme was an aspect of Catholic ‘self-help’ which rose in tandem with the Catholic revival in Scotland. Interestingly, and perhaps inevitably the formation of a football club to raise funds for the needy was also in this tradition of Catholic ‘self-help’.

Walfrid had witnessed the explosion in popularity of association football in Scotland and, according to Connolly, ‘envisaged the prospect of harnessing the potential of Glasgow’s Irish Catholic diaspora through the vehicle of a football club’.[4] This was not without precedence, as this had been achieved in Edinburgh several years previously with the formation of Hibernian Football Club.

Walfrid’s vision of a football club which provided for the needs of the poor was, however, a defining moment for the marginalised Irish community in the city. Indeed, it soon became a symbol of hope for a people still regarded by many as alien. As Connolly points out ‘Celtic, born out of the Irish immigrant community in Glasgow to which Brother Walfrid belonged, came to symbolise a club sympathetic to the needs of its community’.[5]

The club’s mission, once established, was clear. A circular which was sent to Catholic parishes around the city as the club was formed made clear it was attached to that proactive social Catholicism which had gripped society. The circular stated:

‘The main object of the Club is to supply the East End Conferences of the Saint Vincent de Paul (SVDP) Society with the funds for the maintenance of the dinner tables of our needy children’.

In Celtic’s early years it raised significant amounts of money for the Irish Catholic poor in Glasgow. Not only was it involved in the giving of alms in this early period, the club also aligned itself with Irish nationalist causes such as the Irish National Land League, founded by Michael Davitt, who would go on to become one of Celtic’s early patrons. Significantly however, the club did not confine itself to Catholic causes. The club’s ledgers reveal that that donations were provided to labour-related causes and organisations such as the ‘Hand-loom Weavers of Bridgeton’.

Connolly does not shy away from criticisms which were levelled at the club in this period. One of the more fascinating aspects of the early years which Connolly devotes time to is the transition from charitable organisation to professionalisation, when the club became focused on maximising profits. This coincided with Walfrid’s departure from Glasgow in 1892.

Connolly’s even-handed approach to the debates which raged in Glasgow’s Catholic press about the direction the club was taking, demonstrates the emotional attachment which some had to the charitable origins of the club. Connolly situates this debate against the backdrop of the commercial development of football in Scotland and the rest of the UK, the need to pay players competitive wages, and of course balancing the books.

This was surely a fascinating time in the club’s early history. The game was increasing in popularity and Celtic could not afford to be left behind, despite its noble beginnings. Nevertheless, the charitable Catholic ethos of the club did not die with the departure of Walfrid. It carried on, just not to the degree it had in the beginning. Walfrid’s influence was still felt among key club personnel in those early years.

Men like Joseph Nelis, John McCreadie, John Conway, and Michael Cairns were former pupils of Walfrid, who had instilled a philosophy of charity and community empowerment in his charges. It was in the club’s DNA and was something which would not easily disappear.

London and Retirement

The departure of Walfrid from Glasgow, moved by his superiors to another parish in the East End of London, did not mean the link with Celtic was severed. On the contrary, he was kept up to date with developments at the club he founded. The legacy of charity and sport, so successfully employed in his time in Glasgow, was also to be found in Walfrid’s London mission.

Here he established a small football team and a cricket team bearing the same name as his more famous club north of the border. The charitable aspect of his mission is also evident, not least in his raising money for the Indian Famine Fund, something which Connolly argues displays an international awareness of the suffering of other communities among the British colonies.

Walfrid was later re-assigned to London where he died in 1915. Connolly’s book deals with many important issues which reach far beyond the man and the football club he established

Walfrid was moved on yet again, this time from his London mission to Grove Ferry in Kent. Here he saw out the last six years of his teaching career at a slower pace until he retired in ill health to the Marist centre of St Joseph’s, Dumfries in 1912. The elderly Brother died in St Joseph’s from a cerebral hemorrhage aged 74 on April 17th, 1915, the same day that Celtic won the Scottish League Championship. The customary humble funeral of members of the Marist Order was observed, except for a Celtic jersey placed on the coffin. A fitting tribute.

Connolly’s book deals with many important issues which reach far beyond the man and the football club he established. A central theme throughout is the sense of charity which guided Walfrid’s life. Connolly shows in the book’s post-script that this core tenet remains part of the modern football club, with the charitable work of the Celtic FC Foundation leading the way in keeping Walfrid’s name alive in the work that they do. The book is not only an important edition to the historiography of the football club, it is also a valuable title in the literature of modern religious history of Scotland and is sure to interest football and non-football fans alike.

Notes

[1] Roger Swift ‘The Outcast Irish in the British Victorian City: Problems and Perspectives’ in Irish Historical Studies, 1987, vol. 25, no. 99, pp 264-276.

[2] Michael Connolly, Walfrid: A Life of Faith, Community and Football (Argyll, 2022), p. 59.

[3] Connolly, Walfrid, p. 56.

[4] Connolly, Walfrid, p. 107.

[5] Ibid, p. 109.