‘Conducive to the improvement of the country’, The Coolattin Wentworth-Fitzwilliam estate, County Wicklow

By John Dorney

Coolattin estate, located in southern County Wicklow, once sprawled across nearly half of the county, taking in thousands of acres of woodland, farmland and mountain.

From its seat at Coolattin house, it witnessed and exemplified, centuries of Irish history, from the colonisation of formerly Gaelic territory under the Elizabethan and Stuart monarchs, to the era of the ‘Protestant Ascendancy’ and their great landed estates. But it also witnessed the eclipse of the political power of this class in the late nineteenth century and finally to their dissolution of their estates in the twentieth.

The Wentworth and Fitzwilliam families who owned the estate shaped the human and also the physical geography of south County Wicklow over a period of over three hundred years. By turns the owners of Coolattin were rapacious colonists and careful conservators, conquerors and liberal reformers, improving landlords and clearers of the tenantry.

Notably also, despite a very late rearguard action in opposing Home Rule, they acceded to their political eclipse and to the sale of the estates essentially without a struggle.

Land ownership at Coolattin

What is now County Wicklow was, throughout the later middle ages, the stronghold of Gaelic mountain clans such as the O’Tooles and O’Byrnes, a fortress outside the control of the English lordship of Ireland.

This was despite the fact that that Lordship was based in the neighbouring city of Dublin and Dublin’s rural hinterland, the English Pale. In fact, the proximity of what the Palesmen referred to as ‘the mountain enemy’ made the Pale’s southern frontier an intermittent war zone, subject to regular raids and incursions, until the end of the 16th century.

This all changed with the victory of the English Crown over the recalcitrant Gaelic clans, including the O’Tooles and O’Byrnes, in the Nine Years War, in 1603. For the first time this established English rule over all of Ireland, including the Wicklow Mountains. County Wicklow was formally shired and created in 1606, the last Irish county to be founded, and vast amounts of land previous belonging to the Gaelic Irish inhabitants was confiscated.

the Wentworth estate was formed in the 1600s after the seizure of land from the Gaelic clans.

Much of southern County Wicklow came into the possession of Thomas Wentworth, the First Earl of Strafford in the 1600s. Wentworth came from a family of aristocrats with large possessions in Yorkshire in the north of England. Coolattin house, near the village of Shillelagh, was constructed here in the early seventeenth century, building on an early 11th century fortress and became became the seat of the Wentworth estate. This eventually comprised about 37,00 acres of land. From 1632 Thomas Wentworth held the position of Lord Deputy of Ireland.

The Lord Deputy was the of governor of Ireland on behalf of the Crown – the direct representative of the monarch. Wentworth, who held this position from 1632, was associated with tough and authoritarian rule in Ireland. His policy of advancing the religious and civil power of the King, Charles I provoked resistance among all quarters in Ireland, from Catholics who feared further confiscation of their lands, to the ‘New English’ or Protestant settlers, who resented his imposition of taxes and feared he was too conciliatory to Catholics.

Recalled to England in 1639, to aid the king in putting down a Scottish rebellion, Wentworth proposed raising a Catholic army in Ireland against them, to the alarm of English Protestants. Wentworth’s policies eventually led to his being attainted for treason by the English Parliament and his execution for alleged treason in 1641 at their insistence, an event which helped to spark Civil War in England between them and the King.

The Wentworth estate, whose owners were supporters of the monarchy throughout the subsequent civil wars, was confiscated by the Cromwellian regime from 1650-1660 but restored to the Wentworths after the restoration of the monarchy and Charles II in 1660.[1]

Wicklow itself was again a site of savage guerrilla warfare in the period, beginning with the rebellion of 1641 and ending with the Cormwellian conquest of 1649-52. The county was considerably depopulated, particularly by the scorched earth tactics of the New Model Army led by General Ludlow in 1650-52. The pre-conquest Gaelic Irish and Catholic landowners were also dispossessed almost entirely and there was extensive English Protestant settlement in the county over the following century, making it the highest concentration of Protestant settlement in Ireland outside of Ulster.

In 1695, Thomas Watson, Earl Rockingham (of Yorkshire) inherited the Wicklow estates of his uncle William Wentworth, 2nd Earl Strafford, who had died childless. The properties passed through the Watson Wentworth line until 1782 when Thomas Watson Wentworth died without heirs. The estate then passed to his nephew Earl William Fitzwilliam who had married Anne Watson Wentworth. From this point onwards it became Wentworth-Fitzwilliam estate.

After the intermarriage of the Fitzwilliam and Wentworth families in the 1780s the family’s holdings in Wicklow reached over 80,000 acres

There were six blocks of the estate and the entire property amounted to some 56,000 acres. When amalgamated with Fitzwilliam’s total holdings in Wicklow, the family’s possessions were even larger at 87,000 acres and held up to 20,000 tenants.[2] The Wentworth-Fitzwilliams were generally resident in England at their seat in Yorkshire and visited their Wicklow estates about two or three times a year.

The main seat of the estate was at Coolattin, originally named Malton House, but later rebuilt and renamed Coolattin House in the early 19th century.

Alongside the main seat of the estate however, were other ‘big houses’, notably Money House at Shillelagh, which was occupied by the agents of the estate, who ran it on a day to day basis.

The Nickson (also spelt Nixon) family served as agents of the Wentworth-Watson-Fitzwilliam estate from at the late seventeenth century until the mid nineteenth century when they were succeeded at Money House by Lawrenson family. Much more than the actual landlord, who would often have been absent in England, local tenants would have dealt with their agents.[3]

Forestry at Shillelagh

One of the most striking ways in which the seventeenth century colonisation of south Wicklow affected the landscape was the deforestation that accompanied it. Prior to 1600, much of the region had been covered by forests.

When Thomas Wentworth, acquired his Wicklow estates in early 17th century these included the Shillelagh oak forests. He initially viewed the destruction of these woods as being necessary as a counter-insurgency measure, since they had long been used as a place of refuge by rebels and bandits – wood-kerne as they were referred to by the English.

However, the clearing of the local forests quickly evolved from military necessity to lucrative business venture. Wentworth and his descendants made a fortune from the timber from these oak woods which was used for tanning, house and ship building and to make pipe staves and iron smelting. Before coal was utilised, oak was the only fuel available in Britian or Ireland that could reach a temperature high enough to smelt iron.[4]

The Wentworth-Fitzwilliam estate exploited the oak woods at Shillelagh intensively, but eventually also came to protect and manage them.

In 1725, much of the oak forest at Shillelagh was sold to an iron-master, Jonathan Chamney, who felled them. By the mid-1700s, woods were generally found on the worst or marginal land in the estate. By 1749, 20% of the Shillelagh estate was wooded and went on producing timber throughout eighteenth century, producing up to half of the estate’s annual income of £3,293. [5]

The famous travel writer Arthur Young visited Wicklow late 18th century (1776-7) and described woods in Ireland as having been ‘destroyed for a century past with the most thoughtless prodigality’.

It was not all ruthless exploitation of natural resources for business reasons, however. Indeed, over time, the owners of the Coolattin estate began to see the oak woods as something that needed to be managed and conserved rather than simply harvested. Coppice woods, which were managed woodlands, with rotational fenced felling, began to be used at Shillelagh as early as 1698.

There was also a deer park with Shillelagh oaks at Coolattin. By the end of the 18th century, therefore, the remaining woods in the Fitzwilliam-Wentworth estate were being managed carefully as a resource. But County Wicklow as a whole was quite deforested by that time, with only 2% covered by woodland compared to 13% in 1700 and far more a century before that.[6]

Rebellion

The politics of the landowners at Coollattin also evolved. The Fitzwilliams, who came into possession of the estate in the late 1700s, were Whig grandees and saw themselves as ‘improving’ and paternal landlords.

William Wentworth Fitzwilliam, the Earl Fitzwilliam became Viceroy (or Lord Lieutenant) of Ireland in 1795 with a liberal reformist agenda including the passing of Catholic Emancipation (that is giving Catholics full and equal rights as citizens), but was opposed by conservative interests in both Dublin and London and was recalled to England before he could carry out his programme.

Fitzwilliam’s recall is often regarded one of the factors that led to the bloody uprising of 1798.[7]

The estate’s seat at Malton House, Coolattin was destroyed during the rebellion, burned by rebel forces. The counties of Wicklow and Wexford suffered from systematic campaigns of house burning by both rebels and loyalists. According to one observer ‘there wasn’t a good house left standing in the county after 1798…..’ [8] In July 1798, after the defeat of the main rebel force at Vinegar Hill, near Enniscorthy, a rebel column from Kilcavan in County Wexford, made a foray northwards into the Shillelagh area.

The Fitzwilliam family were liberals, favouring Catholic Emancipation, but their seat at Malton House was burned during the 1798 rebellion.

The contemporary loyalist historian Richard Musgrave, who characterised the rebellion as a Catholic insurrection, wrote of southern County Wicklow that, ‘All Protestants houses on both sides of the road from Hacketstown to Rathdrum were burnt’, by ‘large rebel bands [who] with cool deliberation proceeded to lay waste to extensive tracts of the county’. [9] Indeed, as well as the estate’s seat at Malton House, some 160 houses in the vicinity were destroyed and several loyalists killed. Local Catholic houses and churches were also, in turn, burnt down by the loyalist Yeomanry.

Contrary to Musgrave’s depiction of religious war, some rebel leaders in Wicklow, such as Joseph Holt, were in fact Protestants. The Fitzwilliams, though of the ruling Protestant caste, were distinctly liberal in their politics.

However, this counted for little in the bloody summer of 1798. Nor were the Fitzwilliam’s liberal politics necessarily true of their agents or their Protestant tenantry. Historian of the rebellion, Daniel Gahan writes, ‘The [Fitzwilliam] estate was in the heart of loyalist south-west Wicklow and was dotted with the houses of Fitzwilliam middlemen’.

Indeed, the officers of Yeomanry who confronted the rebels at Shillelagh were Augustus Nickson, whose family at Money House managed the estate and Henry Chamney, whose family ran the Fitzwilliam’s timber and iron works. The loyalist forces were worsted in a skirmish near Shillelagh, losing several dozen killed, including Nickson and Chamney, before retreating to the substantial house of Chamney, where they held out until the rebels retreated back into County Wexford.[10]

Despite the destruction on their estate, in the aftermath of the rebellion, the Fitzwilliams seem to have been in the forefront of trying to promote reconciliation between the religious-communal groups.

The Fitzwilliams not only allowed Catholic churches to be built on their estates in subsequent decades, but also in some cases donated land and contributed towards the cost of erecting the church. Schools, both Catholic and Protestant, were also encouraged and many were either wholly or partly maintained from the estate’s revenue.[11] In all some 32 schools were built on the estate in the early nineteenth century and the Earl insisted that Catholic clergy should have the right to teach in them. [12]

Between 1803 and 1807, Coollattin House, previously Malton House, was rebuilt as a Georgian mansion, the structure that still survives today.

The rebuilding programme after 1798 saw the development of sawmills, a building yard, the forests and slate quarries. The Fitzwilliams also contributed to providing widows’ pensions and to the upkeep of hospitals, dispensaries and other charities.[13]

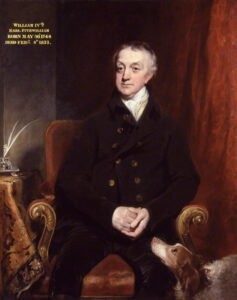

Unlike some other great estates, the Wentworth Fitzwilliam estate appears to have been profitable, unhindered by major debt and was kept intact throughout the 19th century, with 5th Earl Fitzwilliam presiding between 1833 and 1857 and the 6th from 1857 to 1902. [14]

Famine and clearance

Ireland in the early 1800s saw a population boom, with its population nearly doubling in forty years to about 8 million. County Wicklow grew from about 80,000 to over 126,000 in the same period.[15]

By the mid nineteenth century it was received wisdom that Ireland was over-populated and its rural areas not productive enough. Whether this could be attributed to failure of the landlord class to develop their estates, or to Ireland’s inability to establish an industrial base, or, as mid nineteenth century commentators sometimes argued, to the laziness and ignorance of the Irish peasantry, it culminated in the catastrophe of the Great Famine from 1845-1849, caused by the repeated failure of the potato crop, in which over one million people died.

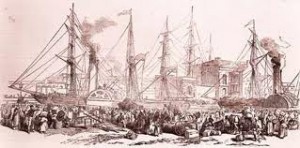

During the Famine, the Earl Fitzwilliam, William Thomas Spencer Wentworth, paid for over 6,000 of his tenants in County Wicklow to emigrate to Canada, including over 2,000 from Coolattin, in a process that lasted from 1847 to 1856. This was widely regarded at the time, not as cruelty but as an act of mercy, in keeping with the family’s liberal politics.

During the Great Famine, Earl Fitzwilliam paid for the passsage of 6,000 of his Wicklow tenants to north America

While many landlords around Ireland, simply evicted their tenants, almost certainly dooming them to death or at best to chaotic flight to the towns or across the Atlantic, the Earl Fitzwilliam, paid for their passage to Canada and arranged for employment in Quebec and St Andrews.[16]

Nevertheless, the clearance on the Fitzwilliam estate contributed to a rapid fall in the population of County Wicklow, from 126,000 in 1841 to just 60,000 in 1901. Today it stands at 142,000, but mainly concentrated in a few coastal towns on the eastern side of the county. Its mountain core today is still largely depopulated.

Alongside what was a relatively humane ‘clearance’, the landlords attempt to encourage agricultural improvements by setting up a ‘Model Farm’ on their estate. This was part of an initiative, funded by the Board of Education, to set up agricultural schools to encourage new and more advanced methods of farming.[17]

The Fitzwilliams established the model farm near Money House as an agricultural school with the aid of public funds in 1840, not long after the scheme was launched by the Board of Education.

The Freeman’s Journal reported on 22 Oct, 1844 that Earl Fitzwilliam of Wicklow had established a model farm ‘for the advantage of his tenantry’. This was part of a wider interest in promoting good farming practices on the Coolattin estate.

In 1863 the Irish Temperance League Journal approvingly noted a temperance society in the town of Tinahely, barony of Shillelagh, and stated that: ‘lovers of agriculture [in the area] may find some hints from the model farm of Earl Fitzwilliam.’ [18]

A travel writer James Godkin visited the Shilelagh area in 1873 and noted that at the;

model farm of Lord Fitzwilliam in which almost boundless fields of corn and green crops are seen stretching over hill and vale as in Lincolnshire. …Earl Fitzwilliam and his family generally visit the place once or twice a year. Great improvements have been carried out by his lordship’s agents throughout the estates including an extensive consolidation of farms; and when the old leases of the middlemen have dropped, the farms have been given to the strongest of the subtenants, while the trees have been bought up in order to their preservations [sic].[19]

Whigs, Land Acts and Home Rule

In politics, the Wentworth Fitzwilliam family remained convinced Whigs or Liberals. Their political attitude in the latter quarter of the nineteenth century was summed up by historian Robert Kee as favouring ‘measures conducive to the improvement of the country, the development of its resources and the development of its people’ and ‘religious equality for all’.

At a time when conflict on the land was sharpening in Ireland, they favoured trust between landlord and tenant, ‘though unhappily’ one Earl admitted, ‘this is not always the case’ and believed that the state should ‘enforce on all landlords principles of equality and fair play dealing towards tenants’.[20]

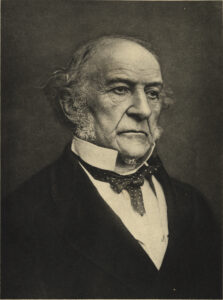

Liberal leader William E. Gladstone visited Ireland in 1877, while he was in opposition, from 17 October to 12 November, and stayed in County Wicklow, staying with a number Whig landlord families including Robert, the Earl of Fitzwilliam. [21]

The Fitzwilliams were in favour of good landlord-tenant relations and religious equality, but were opposed to Home Rule.

However, times were changing in Ireland and the days of the landlord, even a liberal one, as leader of society were threatened by the newly emergent mass politics, personified in Ireland by the Land League and Irish Parliamentary Party. Deference to landlords was breaking down in Ireland with the widening of the right to vote and of the secret ballot and the rise of organised nationalist parties.

Led by the Fitzwilliams’ fellow County Wicklow landowner, Charles Stuart Parnell, the ‘Land War’ of 1879-81 saw tenant farmers extract from Gladstone, then Prime Minister, a series of Land Acts which made it very difficult for rents to be raised or tenant to be evicted.

During the ‘Land War’ – a period of rent strikes, boycotts and other strife in rural Ireland, Earl Fitzwilliam offered his Irish tenants a rent reduction of 50%; but relations nevertheless remained strained.

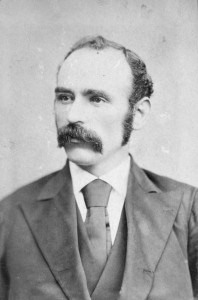

Land League and nationalist leader Michael Davitt speaking at Wexford 1888, decried the idea that the Fitzwilliams, as Liberals, were more benign than more hardline Conservative landlords and said that the nationalists of Wicklow should ‘blush with shame’ for subscribing to ‘a testimonial to be presented to Earl Fitzwilliam’ on his fiftieth marriage anniversary.

He acknowledged that Fitzwilliam was not, like the Earl Clanricarde, in the west, ‘a rack renter and exterminator’ but ‘this in no way extenuates the fact that, were Earl Fitzwilliam twenty times as good a landlord as they say… he is still a supporter of the infamous system that is responsible for the ruin and degradation of Ireland’.

Davitt also pointed that one of Fitzwilliam’s sons had recently stood for election in Doncaster in England, as a Liberal Unionist, and opposed Home Rule for Ireland. In Doncaster, Fitzwilliam had, according to Davitt ‘appealed to the electors of that constituency to return him, in order to crush the movement of which Mr. Parnell is the head’.[22]

The rise of the Home Rule movement under Parnell had resulted in a painful rupture between the 6th Earl and his former friends, Charles Stuart Parnell and the Prime Minister, Gladstone. Though the first Home Rule Bill was defeated in 1886, the days of the Landlords as the ruling class in Ireland were coming to an end.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, Conservative British governments had passed two further land acts, in 1903 and 1908, which subsidised tenants to buy their holdings for their landlords.

This policy, though conceived of as a means of alleviating nationalist demands for self-government, by conceding land reform, ultimately disinherited the old landed class in Ireland. It also formed a central plank of Irish nationalist demands and economic bedrock for a small farming class that would form the basis of the twentieth century Irish middle class.

Most of the Coolattin estate was sold to its tenants under the 1903 Land Act.

Irish nationalist MP James O’Connor enquired in 1906 whether the Fitzwilliam estate had been sold and was told by the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Bryce, that ‘The Estates Commissioners inform me that 60,422 acres of the estate of Earl Fitzwilliam have been sold to 1,055 tenants under the Land Act of 1903.’ The cost of the sale £536,016, to be paid to the Fitzwilliam estate in advance by the state and to be paid back over between 23 and 26 years by the tenants.[23]

Following a meeting between the tenants and the estate’s agent, Frank Brooke, in 1903, the 7th Earl Fitzwilliam had agreed to the sale of his estate though he ‘wished to retain the right to hunt, shoot and fish on the Estate’. It was alleged, in some quarters, that in 1904 and 1906 Fitzwilliam had coerced tenants into buying land on his terms, by bringing forward the date upon which rent was due, and in serving eviction notices for those who had fallen behind on the rent.[24]

It may well have been that selling the ‘tenanted lands’ as opposed to the demesne, that belonged directly to the estate, was more cost effective than dealing with an increasingly assertive and demanding tenantry. In the case of the Fiztwilliams, such was their fortune from other possessions that the loss of rental income of some of their estate in Wicklow did not trouble them very much financially. The 7th Earl Fitzwilliam 1902, inherited assets including coal mines and also very large estates in the north of England making him one of Britain’s richest men.

Nevertheless, in a letter of 1903, the Earl sounded a note of some regret of the sale of his lands in Wicklow, stating that ‘I must confess that I am not in the least anxious to part with the Estate which has formed a direct heritage in my family for generations, but as times change we have to change with them’. [25]

The assassination of Frank Brooke

The demesne lands associated with Coolattin House remained in Fitzwilliam possession, managed by the agent Frank Brooke, who had run the estate since 1887. [26]

Whereas the 7th Earl Fitzwilliam could look on land reform and even Home Rule for Ireland with only sentimental regret, it was not so, for men like Frank Brooke, whose roots lay deep in the Irish Protestant tradition and who perceived Home Rule as a potentially fatal rupture of the connection with Britain. Brooke was from Lisnaskea County Fermanagh and was a cousin to future Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

He was a member of the Orange Order and had stood as a unionist candidate in Fermanagh. He also served as Justice of the Peace in Fermanagh and was chairman of the Dublin South Eastern Railway Company [27]

In the wake of the First World War, with the rise of the Sinn Fein party and their declaration of Irish independence, Frank Brooke offered his services to the Lord Lieutenant, fellow Irish unionist Sir John French, to help put down the separatist movement. He sat on a seven-man panel of close advisors to the Lord Lieutenant. IRA Director of Intelligence Michael Collins marked Brooke out for assassination.

Frank Brooke, the agent who ran the estate at Coolatin, was assinated by the IRA nin 1920 for his role as an advisor to John French, the Lord Lieutenant.

One of the members of Collins’ Squad, or hit unit, Wicklow man Vinny Byrne, recalled that he and two others cycled from Dublin to Wicklow where ‘Brooke lived in a big demesne … called “Coolattin”, Shillelagh’. Finding the house guarded by a policeman however, they returned to Dublin, where they later ambushed and shot Brooke dead at Westland Row train station on 30 July 1920. [28]

According to Kevin Lee, Brooke’s ‘ funeral was a sombre occasion. Former tenants walked two deep and carried floral wreaths in front of the cortège as it proceeded slowly from his residence, Ardeen House, to the church. The mourning party included Earl Fitzwilliam who had travelled from Yorkshire for the occasion. Brooke was the only land agent at Coollattin to be assassinated, and his murder was totally unrelated to the discharge of his duties there.’[29]

It is significant that Brooke was killed for political, not agrarian or land related issues. For one thing the estate at Coolattin had never been characterised by social conflict. But it also demonstrated how Ireland was changing. From the point of view of mainstream Irish nationalism, the battle for control of the land had already largely been won by 1920. For the most part, the old landed class were irrelevant to the new mass politics. It was only where unionism had overwhelming demographic strength, as in north east Ulster, that it was still a potent force.

To quote Kevin Lee again, ‘The 7th Earl Fitzwilliam had no interest in Brooke’s politics, and in fact took no side, even as the Irish War of Independence was raging. As the IRA was planning and perpetrating the assassination of his agent, William Fitzwilliam’s prime concern lay in the design and construction of his private nine-hole golf course in his beloved Coollattin.’[30]

Sale of the house and demesne

The 7th Earl, William Wentworth Fitzwilliam died aged 70 in 1943. His son Peter Wentworth Fitzwilliam, the 8th earl served in British commandos and special forces in the Second World War, died, aged 37 in 1948, in an air-crash in France. The Coolattin estate in County Wicklow, was inherited by his thirteen-year-old daughter, Lady Juliet Tadgell. [31]

The 7th Earl, William Wentworth Fitzwilliam died aged 70 in 1943. His son Peter Wentworth Fitzwilliam, the 8th earl served in British commandos and special forces in the Second World War, died, aged 37 in 1948, in an air-crash in France. The Coolattin estate in County Wicklow, was inherited by his thirteen-year-old daughter, Lady Juliet Tadgell. [31]

Fitzwilliam’s widow, Olive, Countess Fitzwilliam, lived on in Coolattin until her death in 1975. The Coolattin estate and the contents of the house were subsequently sold.

In 1977, the house was sold with 3,300 acres by Lady Juliet Wentworth-Fitzwilliam for £3 million to Michael Brendan Cadogan and Pat Tatton. Within a year, Cadogan sold £725,000 worth of the house’s contents in a private deal. He then sold a further 1,000 acres of the land before selling the estate and contents to Michael Stanley and Pat Tatton, who had been involved in the original sale.

The house and demesne grounds were sold in 1977. The title of Earl Ftizwilliam became extinct in 1979.

The house was sold again in 1983 with 63 acres of land for £168,000. Coolattin was put on the market again in 1995 when Coolattin Golf Club bought the house and 60 acres to extend the golf course to 18 holes.[32] The house was put up for sale again in 2016.

The famous oak woods at Coolattin suffered their worst destruction since the 1600s in the 1970s as the new owners felled many of them, exporting the oak as high quality veneers and replaced sections with spruce and oak, much to the consternation of local conservationists. Whereas the Wentworth-Fitzwilliams had come to see the woods as their patrimony, the new owners, much like the Wentworths themselves in the 1600s, exploited them ruthlessly for profit.

Only the personal intervention of then Taoiseach Charles Haughey saved one portion of the woods, at Tomnafinnogue. Wicklow County Council took over the wood for a period before a sale to a forest management company, Veon, in 2016, who embarked on a programme of replanting native oaks and helped to restore sections of the woodlands.

The Coolattin estate, once the seat of a tremendously wealthy and powerful dynasty in Ireland, is today largely a site of tourism and recreation.

Following the death of William Wentworth Fitzwilliam, the 10th Earl Fitzwilliam in 1979, without children, the title became extinct.

References

[1] Melvyn Jones Landscapes Volume 1, 200, issue 2. Collattin House as it now exists was constructed in the early 1800s, but the first fortified house and residence there dates back to the 11th century.

[2] Melvyn Jones, Coppice Wood Management in the Eighteenth Century, An Example from County Wicklow. Online here.

[3] The Irish Times of October 30, 1877 reported the Munny farm on the Fitzwilliam estate, to be about 300 acres and managed by Mr Ralph Lawrenson, ‘who was for nearly 50 years clerk and under agent on the Coolattin estate. Michael Lawrenson (presumably a relation) managed the neighbouring farm at Killenure

[4] http://www.countywicklowheritage.org/page/the_last_county_-_agriculture_and_industry?path=0p4p67p

[5] Melvyn Jones, Coppice Wood Management in the Eighteenth Century, An Example from County Wicklow.

[6] Nigel Everett, Book review, The Woods of Ireland a History, Nigel Everrett, History Ireland, https://www.historyireland.com/the-woods-of-ireland-a-history-700-1800/

[7] Thomas Bartlet, Kevin Dawson, Daire Keogh, Rebellion, the 1798 Rebellion p.44-45

[8] Wicklow Heritage, teh Lact County, 1798 rebellion, http://www.countywicklowheritage.org/page/the_last_county_-_the_1798_rebellion

[9] Richard Musgrave, Memoir of the Different Rebellions in Ireland P388-389, 390

[10] Daniel Gahan, The People’s Rising, Wexford 1798, Gill & MacMillan, Dublin 1995, p.266-267

[11] Jim Rees, Surplus People from Newcastle and Ballyvolan (continued/1) Greystones, Archeological and Historical Society, Journal Volume 5 2006

https://www.greystonesahs.org/gahs3/index.php?id=228

[12] Stephen Cooper, Frank Brooke, A Victim of the Troubles, http://www.chivalryandwar.co.uk/Resource/FRANK%20BROOKE,%20A%20VICTIM%20OF%20THE%20TROUBLES.pdf

[13] Stephen Cooper, Frank Brooke, A Victim of the Troubles

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Last County – Population Trends, Wicklow Heritage, https://heritage.wicklowheritage.org/topics/the_last_county/the_last_county_-_population_trends

[16] The Landlords of Coolattin estate, https://coolattin.wordpress.com/about/landlords-of-the-coolattin-estate/

[17] John Conlahan, The Daring First Decade of the Board of National Education in Ireland

[18] The Irish Temperance League Journal, Volumes 1-3

Online here

[19] Walker’s Handbook of Ireland (1873) by James Godkin P.189-190 Online here.

[20] Robert Kee, The Laurel and the Ivy, the Story of Charles Stewart Parnell and Irish nationalism. Hamish Hamilton, London, 1993. p. 41-42.

[21] Richard Shannon, Gladstone: 1865-1898 – Page 260, 1999

[22] Stephen Cooper, Frank Brooke, A Victim of the Troubles

[23] Fitzwilliam Estate. Wicklow. HC Deb 22 May 1906 vol 157 cc1140-11140

[24] Stephen Cooper, Frank Brooke, A Victim of the Troubles

[25] Ibid.

[26] Kevin Lee, The assassination of Coollattin land agent, Frank Brooke, 30 July 1920 —https://issuu.com/terrhughes/docs/ebook-extra-compress/s/12775414

from Wicklow and the War of Independence by Wicklow County Archives

[27] Ibid.

[28] Vinny Byrne, Bureau of Miliray History WS0423 p.45-46

[29] Lee, the Assasination of the Coollattin land agent Frank Brooke

[30] Ibid. Lee.

[31] Irish Times June 25 2016, Great country house sale at Coolattin,

https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/homes-and-property/fine-art-antiques/great-country-house-sale-at-coolattin-1.2696317

[32] https://www.independent.ie/regionals/wicklow/arklow-news/coollattin-house-in-shillelagh-is-sold/40851480.html