The Anti-Jazz Campaign

Cathal Brennan looks at why Jazz music was once thought to be ‘the greatest danger to Irish civilisation.’

Cathal Brennan looks at why Jazz music was once thought to be ‘the greatest danger to Irish civilisation.’

In the wake of the First World War there was a feeling that traditional morality and deference to parental and state authority had been severely eroded in Europe and North America. In Ireland this view was heightened by the years of revolution in the wake of the First World War.

With the founding of the Free State, and the victory of the pro – Treaty forces in the Civil War, both church and state sought a return to a traditional, conservative and deferential role for the Irish people. The prominent position many women took on the anti – Treaty side was attacked as part of a wider degeneration in Irish society.

The veteran Sinn Féiner, P.S. O’Hegarty, dedicated a whole chapter in The victory of Sinn Féin to the role of women in the Civil War. It was headed ‘The Furies – Hell hath no fury like a woman …’

The Catholic Church’s efforts to assert social control over the population were generally supported by the state but when elements of Catholic authoritarianism sought to challenge the state, they could find that when government ministers were directly challenged they could make formidable enemies.

Context – “ordinary feelings of decency and the influence of religion have failed”

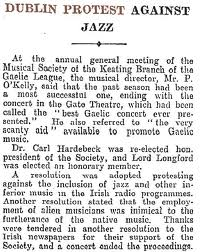

The Anti – Jazz Campaign of 1934 was a coalition of cultural nationalists, alarmed by the influence of foreign music and dancing, and the Catholic Church. The Ireland of the 1930s was beset by many social and economic problems. Unemployment, poverty and emigration were major difficulties for the new state, but the main issue, from the Catholic Church’s point of view, was sexual immorality and unsupervised dancing by young people. Among some Irish language enthusiasts only the restoration of Gaelic would insulate the Irish people from the influence of the immoral British tabloids and obscene literature which was available in English.[1]

In the latter half of the 1920s, the Catholic Church believed the country was being swamped by a tide of depravity and the hierarchy’s demands for legislation on issues of personal morality became more vocal.[2] The Free State government responded by instituting the Carrigan Committee. The Committee viewed itself as operating in a distinct context, emphasising the “secular aspect of social morality”.[3]

In the latter half of the 1920s, the Catholic Church believed the country was being swamped by a tide of depravity

Under the terms of our Reference we had to consider the secular aspect of social morality which it is the concern of the State to conserve and safeguard for the protection and well-being of its citizens. (Carrigan, 1931:4)

The Committee interviewed witnesses in private and their report was completed in 1931. None of the evidence was recounted in the press and the final report was never published.

The report regarded illegitimacy as one of the main causes of vice and crime in society. The report referred to the ‘degeneration in the standard of social conduct’ and attributed it primarily,

… to the loss of parental control and responsibility during a period of general upheaval which has not been recovered since the revival of settled conditions. This is due largely to the introduction of new phases of popular amusement, which being carried out in the Saorstát in the absence of supervision, and of the restrictions found necessary and enforced by law in other countries, are the occasions of many abuses baneful in their effect upon the community generally and are the cause of the ruin of hundreds of young girls, of whom many are found in the streets of London, Liverpool and other cities and towns in England. The ‘commercialised’ dance halls, picture houses of sorts, and the opportunities afforded by the misuse of motor cars for luring girls, are the chief causes alleged for the present looseness of morals.

The report attached very little importance to the social and economic conditions of the time. The failure to highlight slum housing in many Irish cities and towns, leading to massive overcrowding, along with the high rates of infant mortality and poor health among poorer classes seems inexplicable considering the level of church involvement in charitable and welfare services but the church was infused with a Victorian morality which prevented the hierarchy from drawing a link between social conditions and social behaviour.[4]

In his evidence to the commission, Garda Commissioner Eoin O’Duffy stated that in the period between 1927 and 1929 sexual assaults on females had risen by 63% and on males by 43%. O’Duffy believed that 6,000 children had been victims of sexual assault in the same period.[5] Rather than use these appalling statistics contained in the commission’s evidence to deal with the problems of sexual crime in the state the Cumann na nGaedhael government decided to bury the report.

When the Report of the Committee on the Criminal Law Amendment Acts and Juvenile Prostitution (Carrigan Report) was circulated to each member of the Executive Council (Cabinet) on 2 December 1931 it was accompanied by a memo from the Department of Justice which said that it might not be wise to give currency to the damaging allegations made in Carrigan regarding the standards of morality in the country.[6] It might embarrass important people to discover that, “ordinary feelings of decency and the influence of religion has failed and the only remedy is police action”. As a result, “It is clearly undesirable,” the cabinet was told, “that such a view of conditions in the Saorstát should be given wide circulation.” [7]

Irish civil servants were particularly scathing of the report.

This section of the report wanders some way from the terms of reference. The committee might equally have concerned itself with housing, education, unemployment or any other matter which might have had an indirect effect on prostitution and immorality. Their suggestions amount almost to a suppression of public dancing.[8]

The danger of the spread of new modes of transport throughout the country was highlighted by Cardinal MacRory in his 1931 Lenten Pastoral. ‘Even the present travelling facilities make a difference. By bicycle, motorcar and bus, boys and girls can now travel great distances to dances, with the result that a dance in the quietest country parish may now be attended by unsuitables from a distance.’

Fr. Peter Conferey and the Anti-Jazz crusade

Virtually all modern dancing in Ireland at the time was referred to as jazz. The increasing ownership of gramophones and wireless sets meant that Irish people were being introduced to a wider selection of music and as returning emigrants from the United States brought back records and sheet music the popularity of ‘jazz’ increased throughout the country.[9]

Virtually all modern dancing in Ireland at the time was referred to as jazz. The increasing ownership of gramophones and wireless sets meant that Irish people were being introduced to a wider selection of music and as returning emigrants from the United States brought back records and sheet music the popularity of ‘jazz’ increased throughout the country.[9]

Leitrim was to become the centre of the Anti – Jazz campaign and its leader was the parish priest of Cloone, Fr. Peter Conefrey. Conefrey was an ardent cultural nationalist and was heavily involved in the promotion of Irish music and dancing and the Irish language. He devoted his life to making parishioners wear home – spun clothes and become self – sufficient in food.[10]

On New Year’s Day 1934 over three thousand people from South Leitrim and surrounding areas marched through Mohill to begin the Anti – Jazz campaign. The procession was accompanied by five bands and the demonstrators carried banners inscribed with slogans such as ‘Down with Jazz’ and ‘Out with Paganism.’[11] A meeting was then held in the Canon Donohoe Memorial Hall organised by Fr. Conefrey and Canon Masterson, the parish priest of Mohill.

Messages were read out from prominent personalities who had given their support to the campaign. Cardinal MacRory heartily wished the Co. Leitrim executive of the Gaelic League success in its campaign against all night jazz dancing which he described as ‘suggestive and demoralising.’[12] He referred to these dances as, ‘a fruitful source of scandal and of ruin, spiritual and temporal,’ and wondered, ‘to how many poor innocent young girls have they not been the occasion of irreparable disgrace and life-long sorrow.’ The cardinal hoped that the Gaelic League could create a strong public opinion against all night dancing.

The President, Éamon de Valera, sent his regrets that neither he, nor any of his ministers, could attend but sincerely hoped that the efforts of the Gaelic League to restore ‘the national forms of dancing’ would be successful.[13]

The bishop of Ardagh and Clonmacnoise, Dr. McNamee, sent his support and condemned all night dances and improperly conduced dance halls. He suggested the formation of a non – political body, under the aegis of the church, along the lines of the French, Jeunesse Agricole Catholique. He hoped this new body could, ‘give young agriculturalists interest and pride in their profession.’[14]

Douglas Hyde also sent a message of support to the meeting and he hoped in future that all dances and games should be Irish.[15]

Canon Masterson, who chaired the meeting, told the assembled crowd that he considered jazz a menace to their very civilisation as well as their religion. He said that after the Treaty of Limerick all vestiges of national life were swept away apart from, ‘the Irish faith and the Irish music.’ He warned the audience that, ‘the man who would try to defile these two noble heritages was the worst from of traitor and the greatest enemy of the Irish nation.’[16]

Fr. Conefrey then got up to speak. He declared that jazz was a greater danger to the Irish people than drunkenness and landlordism and concerted action by church and state was required. He called on the government to circularise Garda barracks to forbid the organisation of jazz dances and to compel dance halls to shut at 11 pm. He also called for the training of young teachers in Irish music and dancing.[17]

Sean MacEntee – ‘A soul buried in Jazz’

The secretary of the Gaelic League, Seán Óg Ó Ceallaigh, then made an extraordinary attack on the Minister for Finance, Seán MacEntee. He condemned the practice of sponsored programmes on the state broadcaster, Radio Éireann, which sometimes included jazz music. He told the meeting that, ‘Our minister for Finance has a soul buried in jazz and is selling the musical soul of the nation for the dividends of sponsored jazz programmes. He is jazzing every night of the week.’[18]

A voice from the floor shouted, ‘Put him (MacEntee) out.’ To which Ó Ceallaigh replied, ‘Well I did not help to put him in,’ and added, ‘As far as nationality is concerned, the Minister for Finance knows nothing about it. He is a man who will kill nationality, if nationality is to be killed in this country.’[19]

This prompted the local Fianna Fáil TD, Ben Maguire, to defend his party colleague. He agreed that the broadcasting was not as national as it should be but he declared that if the minister was to be attacked personally he would take up the challenge on his behalf. He added, ‘I hope it will not pass unanswered and that the minister will be given the opportunity of defending himself.’[20]

Fr. McCormack from Granard, Co. Longford, informed the meeting that GAA clubs were some of the worst offenders for organising jazz dances while B.C. Fay of the Ulster Council of the GAA called for legislation regulating the use of dance halls and excluding young people under the age of 16 from entering them. He also warned that it was a sign of degradation to see young women smoking in public.[21] The meeting was then followed by a concert and céilí in the hall.

The Minster gets involved

The sponsorship of programmes on Radio Éireann, or 2RN as it was originally known, had long been a source of contention for some. Irish companies paid £5 per five minutes of sponsorship while foreign companies were charged twice this amount. In the first three months of 1927 advertising revenue amounted to £200 but the entire revenue for 1928 was just £28. By 1929 revenue had risen to £50 per annum.[22] The secretary of the Department of Posts and Telegraphs, P.S. O’Hegarty, thought that advertising on radio should be allowed to die a natural death while Seamús Clandillon, the station director, declared that, ‘from a programme point of view they are a nuisance and are regarded by the listeners as an impertinence.’[23]

The first sponsored programme, by Euthymol toothpaste, was broadcast on the 31st December 1927. Frequently these programme would use popular or dancehall music to entice the audience and would intersperse advertisements for their clients throughout the show. Radio Éireann could be received throughout Western Europe and the sponsored programmes picked up a significant following outside Ireland.

When faced with an attack on fellow minister MacEntee on Irish radio, Gerald Boland cancelled the broadcast.

Sean Óg Ó Ceallaigh was due to deliver a radio lecture on ‘Irish Culture: It’s Decline’ on the 11th of January 1934. The Minster for Posts and Telegraphs, Gerald Boland, stepped in and had the broadcast cancelled. Justifying the cancellation, Boland stated that, ‘Mr. Ó Ceallaigh had made a grossly unfair and unjustified personal attack on the Minister for Finance at Mohill on the 1st of January and must have known that Mr. MacEntee was not responsible for the conduct of the broadcasting service. I was determined to ensure that he would not avail of the opportunity presented by his broadcast to renew his attack.’[24]

Ó Ceallaigh stated that he had submitted the text of his lecture to the station director a week in advance and no objection had been made but Boland questioned the capacity of Ó Ceallaigh to stick to his prepared script. In an interview on the subject, Boland said, ‘that if he (Ó Ceallaigh) wants to make a personal attack on a Minister he can do it, but he will not do it over the radio if I can help it.’[25]

Boland also sought to reassure the public that he was taking steps to curtail the amount of jazz music broadcast on Radio Éireann and to replace it with classical music and military marches. The Minister had already used his influence to have the words of ‘a foreign type of Good Night song,’ that one of the programmes concluded with, excised and he announced that he was prepared to forego the revenue derived from sponsored programmes rather than have them ‘serve to advance jazz.’ [26]

‘The fight against imported slush’

On the 20th of January, the Leitrim Observer carried a remarkable opinion piece addressed to the ‘Gaels of Breffni’ from ‘Lia Fáil and fellow Gaels.’ The letter began by telling the Gaels of Breffini that, ‘we are with you in the fight against the imported slush. Keep out, we say the so – called music and songs of the Gall; his silly dances and filthy papers, too. We can never be free until this is done.’[27]

After listing everyone from Henry VIII to the Black and Tans who had tried to destroy Irish ‘faith and nationality,’ the piece warned that, ‘Satan and Saxonland are now endeavouring to sap its foundations by sullying the virtue of the children of the Gael… Let it ring through Erin and beyond her shores. Let the pagan Saxon be told that we Irish Catholics do not want and will not have the dances and the music that he has borrowed from the savages of the islands of the Pacific. Let him keep them for the 30 million pagans he has at home.’[28]

‘Let the pagan Saxon be told that we Irish Catholics do not want and will not have the dances and the music that he has borrowed from the savages of the islands of the Pacific’

The letter reminded the readers of the work that the founders of the Gaelic League had done and urged them to follow their example by making Ireland, ‘a Gaelic nation free from the ties of Anglicisation and uncorrupted by baleful influences.’[29]

It warned the people of Leitrim not to turn away from the special mission God had given Ireland to bring Christian civilisation throughout the world and not to ‘disgrace the heroic saints and martyrs of our race… The West, we are sure, will not now slumber but rush forth again to expel the last and worst invader – the jazz of Johnny Bull and the niggers and cannibals.’[30] Concluding the piece Lia Fáil wrote that, ‘to be slaves of Saxonland is bad enough, but to belong to Satan! Perish the thought!’

‘A sectional political body’?

The attack on Seán MacEntee was the main item of business at the next meeting of the Coiste Gnotha of the Gaelic League. Micheál Ó Maoláin moved a motion regretting the attack on the Minister. Ó Ceallaigh had been speaking in Mohill on behalf of the Coiste Gnotha and had no authority from that body to do anything other than support the Anti – Jazz Campaign and explain the objects of the Gaelic League. Ó Maoláin proposed that an apology should be delivered to the Minister for the personal insult given to him in the name of the Gaelic League.[31]

Ó Maoláin warned the meeting that the remarks had created ill feeling towards the Gaelic League amongst many Fianna Fáil supporters and risked turning the League into a sectional political body. Seán Beaumont seconded the motion.

Ó Ceallaigh replied that he stood over everything that he had said in Mohill. The Minister, as a prominent member of the government, could give a good or bad example to the public. He told the meeting that it was well known that the minister was a regular attendee at foreign dances, and sometimes acted as an adjudicator. Latterly, he was going so often, ‘that one would think he was going in for an endurance competition.’[32]

Ó Ceallaigh condemned the parsimonious nature of the Minister when the League had requested money from the Department of Finance to fund Irish dancing instructors for teacher training colleges and to assist with the collection of Irish music. He assigned the worsening in programme standards in Radio Éireann to the fact that the International Broadcasting Company felt that jazz appealed to the English public and the Minister had supported this view as it ensured steady advertising revenue.[33]

Ó Maoláin’s motion was defeated by ten votes to six but a subsequent motion by Fionán Breatnacht, commending Ó Ceallaigh’s Mohill speech, was ruled out of order.

Jazz- ‘borrowed from the language of the savages of Africa’

Fr. Conefrey was asked to chair the February meeting of the South Leitrim Executive of the Gaelic League held in Ballinamore. He thanked all the people who had sent messages of support to the campaign, particularly the Irish National Teachers Organisation, ‘who are willing to do everything possible both for Church and State.’ Conefrey responded to those who asked ‘what is jazz’ by stating that, ‘the Anti – Jazz Campaign excludes no dance that is in keeping with public Christian decency.’ He described jazz as, ‘something that should not as much be mentioned among us and is borrowed from the language of the savages of Africa and its object is to destroy virtue in the human soul.’[34]

Conefrey declared that some of the worst offenders were the Gardaí, who were regularly holding all night jazz dances, ‘even since the Anti – Jazz campaign started,’ and, in most cases, bars were open and the, ‘people attending them are blinded with drink.’ He called this a disgrace and de Valera should, ‘be ashamed of his face to stand by and allow this conduct to be carried on.’ Conefrey called on the Minister of Justice to take action and introduce céilís in every barracks in the country.

Conefrey condemned the criticism of Seán Óg Ó Ceallaigh over his remarks about Seán MacEntee. He told the meeting that he admired Ó Ceallaigh for having the courage of his convictions and asked why should the Gaelic League not criticise Ministers when they do anything not in keeping with Irish traditions? ‘We all agree that Mr. MacEntee has a past record of which any Irishman should feel proud of, but why should he stain that record now by indulging in this jazz dancing? This is not what he fought for and this is not what Pearse and O’Rahilly died for. He is a Minister of the State and should lead in giving the good example.’[35]

The Dance Halls Act 1935

The Anti – Jazz Campaign ran out of steam as 1934 progressed but due to clerical pressure the government introduced the Dance Halls Act of 1935. Anyone intending to hold a public dance now needed a license from a district judge. Many priests felt it their duty to promulgate the Act throughout their community and often accompanied Gardaí on their raids of unlicensed dances.[36]

From 1935 on, partly in response to the campaign, a licence was needed to hold a public dance

The Act was so wide reaching that the owners of private homes who held dances for friends and neighbours without a license were sometimes prosecuted. Ironically, many of these dances in rural private homes featured traditional Irish music and dancing.

The 1930s saw a large increase in the building of parochial halls throughout the country. The local clergy applied successfully for dancing licenses and the money raised became an important source of revenue for parishes and for the government, who took a 25% tax on each ticket sold. The socialising of young men and women at dances would now take place under the strict supervision of the local priest.[37]

Ireland was not unique in the moral hysteria generated by the Anti – Jazz Campaign. Similar campaigns were prevalent throughout Europe and the United States at the time. Unfortunately, the racial and anti – Semitic undertones of the campaign were replicated across the world. According to J.H. White there was, ‘a difference of degree, not kind, between the anxieties expressed in Ireland and those found in many other countries.’[38] An older generation frightened and bewildered by the younger generation’s interest in music, clothes and dancing was a feature of every decade throughout the 20th century, and is to this day.

Despite worries by some in the Hierarchy, Fianna Fáil proved as willing as their predecessors in government to employ the power of the state in safeguarding Catholic moral standards.[39] The Anti – Jazz campaign highlighted some of the uglier aspects of cultural nationalism among those that believed that only a Gaelic and Catholic identity could be truly considered Irish. The Dance Hall act was also a victory for the Catholic Church who throughout the 1920s and 30s had seen many of their demands for legislation dealing with censorship and personal morality enacted. Rather than deal with the real underlying factors leading to sexual immorality in Ireland the state preferred to use the church as an agent of social control.

Bibliography:

Leitrim Observer, 6th January 1934,

Leitrim Observer, 13th January 1934.

Leitrim Observer, 20th January 1934.

Leitrim Observer, 10th February 1934.

Kennedy, Finola, The Suppression of the Carrigan Report: A Historical Perspective on Child Abuse, Studies (Vol. 89, No. 356), 2000, p. 356.

Maume, Patrick, The Novels of Canon Joseph Guinan, New Hibernia Review, Irish Éireannach Nua, (Vol 9, No. 4), 2005.

McGarry, Fearghal, Eoin O’Duffy, a Self-Made Hero (Oxford, 2005).

Ó hAllmhuráin, Gearóid, Dancing on the Hobs of Hell: Rural Communities in Clare and the Dance Hall Act of 1935, New Hibernia Review, Iris Éireannach Nua, (Vol. 9, No. 4), 2005.

Pine, Richard, 2RN and the Origins of Irish Radio (Dublin, 2002).

Smyth, Jim, Dancing Depravity and all that Jazz: The Public Dancehalls Act of 1935, History Ireland (Vol. 1, No. 2), 1993.

White, J.H., Church and State in Modern Ireland (Dublin, 1980).

[2] Smyth, Jim, Dancing Depravity and all that Jazz: The Public Dancehalls Act of 1935, History Ireland (Vol. 1, No. 2), 1993, p. 52.

[3] Kennedy, Finola, The Suppression of the Carrigan Report: A Historical Perspective on Child Abuse, Studies (Vol. 89, No. 356), 2000, p. 354.

[4] Smyth, Jim, Dancing Depravity and all that Jazz: The Public Dancehalls Act of 1935, History Ireland (Vol. 1, No. 2), 1993, p. 52.

[6] Kennedy, Finola, The Suppression of the Carrigan Report: A Historical Perspective on Child Abuse, Studies (Vol. 89, No. 356), 2000, p. 356.

[8] Smyth, Jim, Dancing Depravity and all that Jazz: The Public Dancehalls Act of 1935, History Ireland (Vol. 1, No. 2), 1993, p. 53.

[9] Ó hAllmhuráin, Gearóid, Dancing on the Hobs of Hell: Rural Communities in Clare and the Dance Hall Act of 1935, New Hibernia Review, Iris Éireannach Nua, (Vol. 9, No. 4), 2005, p. 10.

[10] Maume, Patrick, The Novels of Canon Joseph Guinan, New Hibernia Review, Irish Éireannach Nua, (Vol 9, No. 4), 2005, p. 87.