Film Review: The Enigma of Frank Ryan

Director: Des Bell

Director: Des Bell

Historical Consultant: Fearghal McGarry

Starring: Dara Devaney, Mia Gallagher, Barry Barnes, Frankie McCafferty,

Reviewer: John Dorney

Frank Ryan lies in bed in his cramped bedsit in Berlin in 1944, listening to the Allied bombs pounding the city outside. In the morning, numbly wandering through the destruction all around him, he reminisces about the circumstances that brought him, IRA leader and anti-fascist fighter in the Spanish Civil War, here to the capital of Nazi Germany – not quite as a collaborator but not as a prisoner either.

So opens the film, described as a ‘docudrama’, The Enigma of Frank Ryan. Frank Ryan is a fascinating character for all kinds of reasons – representative of the post-civil war IRA and its attempts to make sense of the fallout of the revolutionary years – left-republican who tried with the Republican Congress, to fuse the Irish Free State’s social failings with its incomplete independence into targets for republicans to overcome – high ranking officer in the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War.

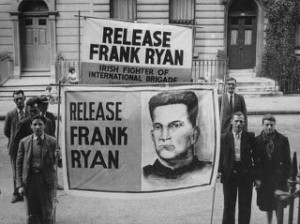

Frank Ryan, IRA leader and anti-fascist died while cooperating with the regime in Nazi Germany. This film asks why

However this film concentrates mainly on his final years, when, liberated from certain death at the hands of his Spanish Francoist captors in Burgos prison, he, along with IRA leader Sean Russell, ended up in an uneasy alliance with Nazi Germany. Underlying this is a central question, how could an avowed anti-fascist have got into bed with these the worst of all enemies?

‘Good versus Evil’ – which side was Ryan on?

We now know of the Nazis’ genocide of European Jews and their litany of slaughter in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union during the Second World War. Timothy Snyder in his recent book ‘Bloodlands’ puts the number of people deliberately murdered by German forces outside of combat situations at about 11 million.[1] The Nazi is regime is thus, justifiably, seen as representing a unique evil, outside of all history and politics.

Association with them in any form therefore invites a kind of demonization and allows all kinds of assumptions to be made about individuals and organizations who worked with them. This film tells Ryan’s story fairly straight and at the same time, gives its main character a relatively easy ride. Ryan cooperated initially with German military intelligence so he would not be executed or imprisoned for life by the Spanish rightists.

Thereafter, he had a chance to return to Ireland in 1940 – on a submarine in which Sean Russell died of a punctured ulcer – but for some reason decided not to do so and returned to Berlin where – no more use to the Germans – he died a sad and lonely death in 1944.

There is no evidence that he was an ideological sympathizer of the Nazis – Adrian Hoare’s biography of Ryan notes that the German intelligence concluded that he was still basically ‘a communist’ who hoped for a Soviet victory.[2]

There is no evidence either, however, that he took any steps to actively oppose the Nazis while in Germany. In the film, the Ryan character demands to know what is going on in the concentration camps, for which demand as director Des Bell acknowledges, there is no documentary evidence.

Frank Ryan’s last years are probably best summed up as a man, who caught in a very difficult situation well beyond his control, did very little other than try to survive.

Those who come to the film looking for an explanation of how Ryan, who on account of his anti-fascism represents ‘good’, could have worked with the Nazis, who represent ‘evil’, will be disappointed. But then so are those who wish to see a clear morality tale in the furious ideological wars in Europe of the 1930s and 40s.

An Irish Context

Where this film is weak, historically speaking, is in showing how a left-wing Irish republican like Ryan understood terms like ‘socialism’, ‘fascism’ and ‘anti-fascism’. Coming out of the debacle of the Irish Civil War, republicans saw that their nationalist revolution had been crushed by the social elite of Irish society – the middle classes, the Church, the press – a sentiment often repeated in the following decades not only by socialists but by such Fianna Fail stalwarts as Todd Andrews, for example, who compared the civil war with Hungary’s ‘White Terror’ or crushing of the communist revolution there in 1919.

Ryan saw ‘fascism’ and ‘anti-fascism’ through a specifically left-republican Irish lense.

Some of the remaining IRA, as a result, led by people such as Peadar O’Donnell and, after a period, Frank Ryan, thus came to adopt a class analysis – James Connolly’s, ‘the cause of Ireland is the cause of labour, the cause of labour is the cause of Ireland’. The next revolution in Ireland would be both national and social – at once severing the remaining ties with Britain and breaking the hold of the supposedly pro-British privileged classes (‘the ranchers’ and the banks were a favourite target) over Irish economic development, to the benefit of workers and small farmers.

This kind of thinking gained some purchase in the IRA, but eventually the leftists, around Ryan, O’Donnell and others such as George Gilmore, left the organisation to form a party known as the Republican Congress. In the context of the Great Depression, the freeing of republican prisoners after Fianna Fail’s coming to power in 1933, and De Valera’s trade war with Britain, the party’s prospects might have appeared promising, but in fact it split at its first meeting and thereafter disintegrated.

If left Irish Republicans such as Frank Ryan saw Irish freedom increasingly in class and semi-communist terms, they also increasingly viewed their ‘Free State’ enemies not only as ‘traitors’ but as ‘fascists’ as well. There were good reasons for this. The more combative elements of Cumann na nGaedheal and the pro-Treaty civil war veterans under Eoin O’Duffy had formed their own street fighting organization – the Blueshirts – modeled on the style and some of the substance of continental fascism.

The Blueshirts did include some hard right-wing and anti-semitic thinkers but also farmers who didn’t want to hand over their cattle to De Valera’s government to pay land annuities and National Army veterans and their sons who were tired of getting beaten up at rallies by the IRA. Republicans like Ryan, though, saw the Blueshirts, much as far leftists did fascist movements elsewhere, as the hard edge of counter-revolution. So when their street-fighting enemies sent a column to Spain to support the right wing military coup against the left wing Republican government, Ryan and other Congress and IRA members naturally projected an Irish canvass onto a Spanish and international conflict.

This Irish context to Ryan’s worldview sadly goes almost unmentioned in the film, which is a pity as it helps to explain the Irish International Brigaders dedication to the Spanish Republican cause. Ryan’s days as a street organizer and sometimes brawler in Dublin also go a long way to explaining his own personal mystique within the Irish republican movement – a charisma which also apparently made him an effective military officer inSpain.

Ryan and the Nazis, a partial explanation?

What is more, Ryan’s dual political identity as Irish patriot and socialist revolutionary goes some way to explaining his cooperation with the Nazis. Apart totally from their getting him out of Burgos prison, where Franco’s forces were busy executing their defeated enemies in 1940, the Germans offered Ryan a chance to return to Ireland in the event of a British invasion – which looked possible in the months after the fall of France in 1940. Given that his goal remained an independent all-Ireland republic, cooperating with Britain’s enemies in this eventuality probably did not strike Ryan as intrinsically dishonourable.

With a British invasion of Ireland a real possibility in 1940, Ryan would not have seen tactical cooperation with the Germans as dishonourable

And even more, given that Ryan understood anti-fascism in terms of socialism versus right wing reaction, the Hitler-Stalin pact of 1939, which agreed an alliance between Germany and the USSR must have been a bitter disillusionment. It must have been difficult to tell any longer, in 1940, who was friend and who was foe.

So Frank Ryan’s tale should not be seen as a morality tale. The anti-fascism he subscribed to was not one of liberal democracy. But nor was his involvement with German intelligence any endorsement of the Nazis’ crimes.

It is, admittedly, a big task for a docudrama, which seeks to entertain as much as to inform, to grapple with all these subtleties, a drawback that the creators of this film acknowledge. Much of its reception will no doubt comprise of debate over whether or not Frank Ryan was a ‘Nazi collaborator’ and what this says, if anything, about the modern Irish republican movement.

Leaving that aside though, the film is still worth going to see. The dialogue is not always wonderful but the story is gripping, especially towards the end, the film uses archival footage cleverly and features a striking performance by lead actor Dara Devaney. If it provokes more people to find out more about Irish and international politics then it will have also been well worth making.