Charles Bianconi and The Transport Revolution, 1800 – 1875

How a self made Italian entrepreneur helped to revolutionise travel in 19th century Ireland. By Brian Igoe.

How a self made Italian entrepreneur helped to revolutionise travel in 19th century Ireland. By Brian Igoe.

By 1800 there were just two overnight stops on the Post Coach from Dublin to Cork, in Kilkenny and Fermoy, and by 1810 it was being done non-stop in 24 hours. By 1815 the coaches from Belfast to Dublin were averaging eight miles – Irish miles – per hour! And then came Charles Bianconi.

In 1800, in Italy, the north of Italy just to the south of the Alps, in the Lombardy village of Tregolo, most people earned their living from silkworms, from silk culture. The Bianconi family was no different. There were four boys and a girl. One of the boys was named Carlo, anglicised as Charles and known to history as Charles Bianconi.

Young Charles Bianconi was not a diligent scholar. Always getting into scrapes and into trouble, in a different age he might have been a great athlete or a footballer, but there were no organised sports in schools in Italy in 1800. So he left school, as was normal, at the age of 16 without much in the way of academic achievement. Now he was an adult and had to earn a living. The people of Tregolo customarily sent their surplus sons to England to find work. The practice was more common at this time because of Napoleon’s expansive ambitions and his requirement for men – surplus males were in extreme danger of being conscripted into his armies.

Bianconi left his native Tregolo in 1800 and ended up, at 16 years old an engraver in Essex Street, Dublin

These journeys to England were arranged through past emigrants who had been and stayed there. In Charles Bianconi’s case his sponsor was a man named Andrea Faroni. Charles’ arrival in London, however, coincided with Faroni’s decision to relocate to Dublin, which is why in the summer of 1802 the young Bianconi found himself, still 16 years old, living just off Temple Bar, near Essex Street, in Dublin.

Faroni was an engraver and printer by trade, and put Charles to work selling his engravings in the street. A year later he was selling them in the countryside as well, travelling as far afield as Waterford. And half way through the following year, having learned his new trade and learned English, as originally agreed with the Bianconi’s in Italy, Faroni set him up on his own.

‘The idea that grew on my back’

Engraving and printing were to be Bianconi’s trade for the next fifteen years or so. In 1806 he set up shop in Carrick-on-Suir, getting his supplies of gold leaf and other materials from Waterford. To Waterford he would go by river, on Charles Morrissey’s boat, which carried eight or ten passengers for 6½d each (‘sixpence ha’penny’, about $3 today).

Engraving and printing were to be Bianconi’s trade for the next fifteen years or so. In 1806 he set up shop in Carrick-on-Suir, getting his supplies of gold leaf and other materials from Waterford. To Waterford he would go by river, on Charles Morrissey’s boat, which carried eight or ten passengers for 6½d each (‘sixpence ha’penny’, about $3 today).

The trip on the meandering River Suir was 24 miles, twice the overland distance, and the river being tidal, the timing of the trips was dictated by the tides. It was at this point that the germ of an idea, planted during his days of humping his wares around on his back, began to take root. “It grew out of my back!” he would joke in later years when asked about how he thought of the idea for his car service. (Commonly in 1800 the word ‘car’ was used to denote a small horse drawn passenger conveyance).

However it was not until 1815 that he could actually do something about it. By this time he had moved to Clonmel, up the Suir from Carrick, and was becoming a successful businessman. He had his own transport by now of course, and was a popular figure about town in his bright yellow gig. He was elected to local charities like the Society for Visiting the Sick Poor, and became a member of the House of Industry.

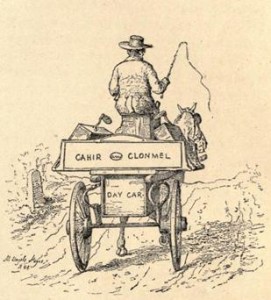

In 1815 he set up a coach service between Clonmel and Cahir

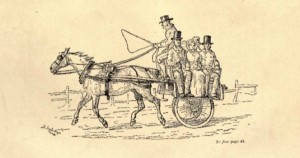

At this time, a tax was levied on Jaunting Cars which put a number of them out of employment. A Jaunting Car, apparently unique to Ireland, is a kind of sprung two wheel cart with seats running longitudinally and the passengers’ feet placed on a footboard, outboard of the wheels, facing out. Nowadays about the only place you see them is in Killarney where they are a popular tourist attraction. Bianconi bought a pair of these, and on July 5th 1815 started his service between Clonmel and Cahir, also on the Suir but further upstream. The end of the war in Europe with the Battle of Waterloo played into his hands at this point, because it flooded the market with cheap horses and out of work horse-men.

It took a while for the concept to catch on, aimed as it was at people who had always walked before, or maybe gone by boat. But when it did, it took off. By the end of the year his cars were running to Tipperary, Limerick, Thurles and Cashel from Clonmel. The next year, 1816, he extended the route system to Carrick and Waterford. He was doing the trip which took the traveller five to eight hours in Morrissey’s boat, in under two hours, and charging 2/- (about $12 today), but the time saved meant a night away from home saved. Cheap travel for the people was here to stay.

Transport in Ireland

In the wider transport scene, canals were also being developed. In 1715 the Irish Parliament took steps to encourage inland navigation, but it was not until 1779 (after a disastrous first attempt a decade earlier) that the first 12-mile section of the Grand Canal was opened.

In the wider transport scene, canals were also being developed. In 1715 the Irish Parliament took steps to encourage inland navigation, but it was not until 1779 (after a disastrous first attempt a decade earlier) that the first 12-mile section of the Grand Canal was opened.

As in England, the canal system, never a threat to the transport of people or mail, were the country’s lifeblood for almost a century before the railways took over the transport of freight. Canal transport at the time was much cheaper and much more reliable than road transport. It could carry heavier and bigger loads in the eighteenth and in the nineteenth centuries. Before the days of the steam engine the boats were provided with long oars for use in the tidal waters, and a small square sail was set on a mast stepped forward. But mostly they were in canals, and towed by horses.

The first of the canals in Ireland, the 165 mile long Grand Canal, was started in 1756 and completed in 1803. It linked Dublin in the east to the River Shannon in the west, and was built largely to move grain and peat (peat is widely used in Ireland for heating) to Dublin. It was also a Godsend to Arthur Guinness, who used the canal to transport his beer and to transport the raw materials to his brewery which was just starting at the time. He even used the water of the Grand Canal for brewing. This stretch of the Grand Canal is still used today by the Guinness Company, though not, one hopes, for the Guinness! Lest we become conceited, it is worth pointing out that the Grand Canal in China was 1,114 miles long and completed over a thousand years earlier!

Canals pre-dated Bianconi’s coaches but were made obsolete by the railways after the mid 19th century

Then, forming a spur to the south at Athy, came the Barrow Navigation which was the canalised River Barrow, partly canal and partly river, established in 1792, 42 miles long. Also starting in Dublin, The Royal Canal served Maynooth and Mullingar before joining the Shannon system 50 miles north of the Grand Canal, near Longford, in 1817.

There were many more – the Newry canal, the Coal Island Canal, the Upper and Lower Boyne, the Ulster Canal, the Ballymore and Ballyconnell, and others, and of course the great Shannon River system itself. Canals were big business in the first half of the 19th century.

Apart from freight, the canals also offered barge-like ‘passage boat’ and ‘fly-boat’ passenger services. The journey from Dublin to Tullamore could be done in less than 9 hours by 1834 in a fly-boat, an average of 7 miles an hour which was faster than most coaches and a great deal more comfortable! They were long ‘narrowboats’ with covered seating for passengers. They were usually towed by two horses (often galloping!) and traveled much faster than any other boats on the canal. They had ‘right of way’ over other boats, which had to release their towlines to let the fly-boat pass. They could also go to the front if there was a queue of boats at lock gates.

The railways spelled the end of nineteenth century canals as viable commercial entities, and gradually they fell into disuse. But now, in the 21st century, they have a new lease of life and narrow-boats on the canals are becoming very popular holiday activities for Irish and visitors alike.

Politics and business

With business thriving in the early 1820s it was time for Charles Bianconi to set up his own workshops, as the cars he was using were subject to breakdowns on the rough roads which of course he did not own. The business was now taking up more time than his printing and engraving business, which he therefore decided to close. By 1818 New Ross had been added to his network, by 1819 Wexford, then Enniscorthy, Kilkenny, Dungarvan. But by this time he was getting short of capital. His horses, their fodder, the cars themselves, repairs, all were eating money and the business was growing fast. Too fast, perhaps.

In the 1826 Waterford by-election, Bianconi changed sides from the Beresfords to Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic Association – for which he was handsomely rewarded

But then, in 1826, came the famous Waterford by-election when the Beresfords – landlord family who had dominated that county’s politics for 70 years – were ousted by the Catholic Association party of Daniel O’Connell – campaigning for Catholic Empancipation. Bianconi had actually been retained by the Beresfords (who were staunchly opposed to Emancipation) to transport their voters to the election, but feelings were running so high that he felt his drivers to be endangered and asked to be released from his contract. The Beresfords reluctantly agreed, and Bianconi was promptly retained by the O’Connell supporting team. He may well have been partly responsible for their resounding success, but from his point of view the important thing was that he was paid £1,000 (perhaps as much as €1000,000 in today’s values) for his services. This was the capital he needed.

Now the network covered by his cars was extended to Cork, Mallow, Tralee, Cahirciveen, Roscrea, Athlone, Sligo – and all the principal towns in the north-west as well as Munster. The network was designed to link towns, especially market towns, rather than concentrate on the main routes served by the Mail Coaches, and these he served at an affordable penny farthing a mile. And so it went on. He now needed bigger cars, although still based on the outside car concept, but with four wheels and two, three, or four horses, the largest carrying up to 16 passengers, 8 a side. He eventually had 100 vehicles travelling 3,800 miles daily calling at 120 towns, and 140 stations for changing horses. Each of these employed up to 8 grooms, and 1,300 horses were needed to pull the cars, eating around 3,500 tons of hay a year, plus 35,000 barrels of oats.

Bianconi’s cars, Bians as they were popularly called, had by 1857 opened up Ireland – opened it to trade, and a novelty, to tourists. More people could get to more markets. Fish from Galway or Waterford or Cork, for example, could be sold anywhere in Ireland the day after they were landed. And perhaps most importantly, quick transport opened Ireland to efficient mail, which could now move as fast as fish. And the cars were all but totally safe. Bianconi and his cars were so popular that they could travel anywhere in Ireland, by day or night, in troubled times or peaceful ones, without molestation The Great Famine of 1845-48 actually helped his business indirectly, because during the famine years thousands of men were employed in relief schemes on Ireland’s roads.

The advent of Railways

But in the late 1840s the railways came along, and posed a major threat, one which many would have thought terminal. Between 1845 and 1850 the Belfast and County Down Railway, the Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway, the Dublin and South Eastern Railway, the Great Southern and Western Railway, and the Midland Great Western Railway were opened, and others were to follow. In the event, after much discussion and consideration, although reducing his fleet of cars somewhat, Charles actually turned this new form of transport to his advantage by restructuring his route system to operate at right angles to the lines served by the railways, servicing their stations. Later times would call this an integrated transport system.

The railways were a potential threat to Bianconi’s business but he adapted his service cleverly

Railways swept the world in the 19th century. The concept of pulling a wagon or cart of some sort on rails had been around for a long time. There are records of a waggonway, 6 kilometres long, known as the Diolkos waggonway. It transported boats across the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece around 600 BC using wheeled vehicles pulled by horses or bullocks, running in grooves in the limestone. The Diolkos was in use at least until the 1st century AD., and the concept was used in other parts of the ancient world. Nearer our own times, the first working waggonway is generally accepted to be the Woolaton Waggonway, built at the end of 1603 in Nottinghamshire, England, to haul coal over a 2 mile stretch. But railways, in the sense of mechanically powered railway systems, only started 200 years later.

They resulted directly from the invention of the steam engine. The famous Stockton to Darlington Railway is the best known of these earlier railways, but a number of short ones opened around England in the first 30 years of the century. However a more sophisticated steam engine was required, and the first proper passenger train service only came along in 1830 with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. This line proved the viability of rail transport, and large scale railway construction now began.

It was four years later, in 1834, that Ireland saw its first railway train. It ran from Dublin to Dun Laoghaire, then called Kingstown, which is a distance of 6 miles. The Dublin and Kingstown railway as it was called, the D&KR, was probably the first purpose built commuter railway in the world. It was very carefully planned, and was designed to carry businessmen form the residential suburbs by the sea, south of the City, into their places of work.

It’s viability was based on a survey which showed that the average daily traffic over the same route was 160 private carriages, 620 private jaunting cars, and 820 public cars (like Bianconi’s). More than sufficient to justify a railway, the promoters reasoned. Especially given the rapidly expanding business going through the port of Kingstown.

The steam engine hauling this first service was a Roberts 2-2-0, with two vertical cylinders, named the Hibernia. She pulled eight carriages. But there was a lot of local opposition from local landowners – then as now! Lord Cloncurry, for example, successfully negotiated for the building of a private foot bridge over the line to a bathing area, complete with a Romanesque temple, a short tunnel and a cutting to maintain his privacy. The same line is now a part of the Dublin Area Rapid Transit system, doing the same job.

In 1843 there was a curious development, and one which could still perhaps be developed – the Atmospheric Railway. It was an extension to the D&KR and ran up a slight gradient for three miles to the town of Dalkey. The system uses air pressure to provide power for propulsion.

Bianconi died in 1875 and left his business to his employees

A pneumatic tube is laid between the rails, with a piston running in it suspended from the train through a seal-able slot in the top of the tube. There are stationary pumping engines along the route, and air is exhausted from the tube leaving a vacuum in advance of the piston. Then there is an arrangement for letting air into the tube behind the piston, so that atmospheric pressure propels it (and the train to which it is attached) forward. The Dalkey Atmospheric Railway operated successfully for ten years.

Around the world railway development proceeded quickly. In the United States, where there were already 23 miles of track in 1830, there were 2,818 miles by 1840 – many built by Irish immigrants. A railway was opened in Belgium in 1835, the first in Continental Europe. Then came a 34 kilometre line in Russia connecting Saint Petersburg to the Tsar’s great Palace at Tsarskove-Selo. Australia joined the Railway Age in 1848, with the Sydney Railway Company’s first line from Bathurst to Goulburn. Then came, India, Egypt, Norway, and Chile by 1854.

Back in Ireland, the next railway to open came five years after the D&KR, the Ulster Railway Company’s first line, from Belfast to Lisburn, which opened in 1839, performing the same commuter service for Belfast as the D&KR did for Dublin. The Great Southern and Western Railway followed, starting in 1844 and reaching Cork in 1849. Gradually, over the next 30 years, most of Ireland was serviced by railway lines, and by the turn of the century, virtually all of it was. By 1920 there were 3,400 miles of line in Ireland. Now less than half remain. At their height they complemented the canal systems, and were complemented in turn by Bianconi’s cars.

Bianconi’s later years

In a speech in 1857 he summarised his service: “My conveyances, many of them carrying very important mails, have been travelling during all hours of the day and night, often in lonely and unfrequented places; and during the long period of forty-two years that my establishment has been in existence, the slightest injury has never been done by the people to my property, or that entrusted to my care; and this fact gives me greater pleasure than any pride I might feel in reflecting upon the other rewards of my life’s labour.”

By this time Bianconi had been Mayor of Clonmel twice and was becoming a significant land owner, with 8,000 acres centred on his house Longfield, overlooking the Suir. “Money melts” he was fond of saying, “but land holds while grass grows and water runs.” He was an excellent landlord, built comfortable houses for his tenantry, and did what he could for their improvement. Without solicitation the government appointed him a Justice of the Peace and a Deputy-Lieutenant for the county of Tipperary.

His son Charles and one of his daughters, Kate, had sadly died before him; another daughter Mary Ann had married Morgan John O’Connell, Daniel O’Connell’s nephew, and so when he died in 1875, he left his business to his employees – a very novel idea at the time.

And so passed Charles Bianconi, a self made man did his part to create modern Ireland.

Brian Igoe is a historian and author. He has written a number of books on Irish history, including The Story of Ireland, which you can view here.