Weapons of his own Forging: Edward Nangle, Controversial in Life and in Death

Patricia Byrne writes about an intriguing character and the impact of Protestant missionary work on Achill Island in the 19th Century.

One hundred and thirty years ago, on Sunday morning 9th September, 1883, the controversial churchman Rev Edward Nangle breathed his last at his home at 23 Morehampton Road, Dublin where he had lain unconscious for two days. ‘Mr Nangle ought to have been buried in Achill’, wrote his biographer Rev Henry Seddall the following year, but the Nangle family decided against this for financial reasons, and his remains were interred in Deansgrange Cemetery, Monkstown.[1]

Edward Nangle was a figure about whom ‘very opposite accounts’ were given during his life, and his legacy continues to be a matter of debate to this day. [2] However, what is perhaps surprising is how quickly after his death contrary views about him were forcefully aired from within the Irish Protestant community

Edward Nangle faced into his last long illness a full half-century after he first laid eyes on the island of Achill in autumn 1831, when he sailed with his wife Eliza, pregnant with their second daughter, on the famine relief ship Nottingham, and ‘on his arrival in the west … he determined to visit Achill’.[3] For some time he had ‘contemplated the establishment of a mission among a portion of the Irish-speaking population’. Achill Island became the focus of his intense and driven personality, inspired in part by his reading of Christopher Anderson’s Historical Sketches of the Native Ancient Irish and Their Descendants. [4]

For almost twenty years … the Achill Mission settlement was the focal point for one of the most bitter religious conflicts in nineteenth-century Ireland

The Mission

On land leased from Sir Richard O’Donnell at the swampy lower slopes of Slievemore, Dugort, there grew up during the 1830s and 1840s a dramatic settlement that included two-storey slated houses, a printing press, an orphanage, hospital, post office, dispensary, corn mill and farm buildings, surrounded by fields reclaimed from the wet mountain slopes. In 1837, just four years after he took up residence in Achill, Edward Nagle wrote:

‘The Missionary Settlement has since grown into a village – the sides of a once barren mountain are now adorned with cultivated fields and gardens … and the stillness of desolation which once reigned is now broken by the hum of the school and the sound of the church-going bell.’[5]

For almost twenty years, until Edward Nangle departed Achill for a church post in Screen, County Sligo in 1852, the Achill Mission settlement was the focal point for one of the most bitter religious conflicts in nineteenth-century Ireland. [6] This conflict is most graphically illustrated in the charges of ‘souperism’ against the Achill Mission in the years of the Great Famine, when Achill Catholics rescinded their faith in return for food and education for their children.[7] The conflict was also dramatically personalised in the furious public polemics between Edward Nangle and Archbishop John MacHale, a fierce opponent of the proselytising movement who was appointed Archbishop of Tuam in 1834, the year the Nangle and his family arrived in Achill. Archbishop MacHale responded vehemently to the Mission activities, making highly-charged visits to Achill, setting up schools adjacent to those of the Mission, and urging island clergy against its activities.

The powerful counter movement by Dr McHale was highly visible by September 1852 – just a few months after Edward Nangle took up his Screen post – when the first Franciscan monks arrived at Bunnacurry, Achill, at the invitation of the Archbishop. The monastery would replicate many of the elements of the Achill Mission: schooling, land reclamation and distress relief.

Edward Nangle returned to Achill briefly in 1879 when he must have surveyed with disappointment the decline of the settlement he had built with such zeal:

‘As I have now completed my 80th year, and am very infirm, I am unable to work for our dear people in Achill as I did for upwards of 40 years of my life.’[8]

In early 1879 he put pen to paper to write The Tourist’s Guide to Achill, published in the Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette, revealing an intimate knowledge of the ‘romantic district’ which he had known for a half-century.[9] A poignant 1880 advertisement for a Dugort bathing lodge in The Irish Church Advocate signalled the approaching end of his association with what had become known as The Colony under the shadows of Slievemore:

‘To be let, the house formerly occupied by the Rev E Nangle. It contains two sitting rooms with four bedrooms, with kitchen, store-room, and servant’s apartment. The house is plainly furnished; it is situated in the Missionary Settlement, commanding a view of Dugort Bay, and the coast of Ballycroy and Erris.’[10]

Immediately following Edward Nangle’s 1883 death, the opposing views of the churchman from within the Protestant community were quickly apparent. The Church Advocate, which had amalgamated with The Achill Herald that Edward Nangle had founded and edited for several decades, stated that ‘few clergymen of the Church of Ireland were better known or more highly valued in his day, as he was a man of much intellectual power, a clear expositor of sound scripture, and a powerful writer…’.[11] The piece praised the ‘singular fidelity’ with which Rev Nangle had pursued his Achill Mission work over many hears.

In contrast, the Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette – an organ of the Church of Ireland – carried a Nangle obituary that portrayed the deceased as ‘an Evangelical of the old school’, while criticising The Achill Herald for being ‘strangely deficient in Church teaching.’[12] The Gazette’s negative critique continued into the following year with a sharp review of Henry Seddall’s recently published biography of Nangle:

‘Everyone has their own idea of heroism, and practices hero-worship after their own fashion. We are free to confess that the late Rev Edward Nangle was not a hero to our mind…’.

The review acknowledged the positive aspects of Nangle’s Achill work, particularly in the famine years, but criticised him as ‘a perfect type of the rugged, uncompromising polemic …[who] fought the battle against Rome with weapons of his own forging…’.[13] In the opinion of the reviewer, ‘a gentler and more tender campaign might have been followed by better and more permanent results’.

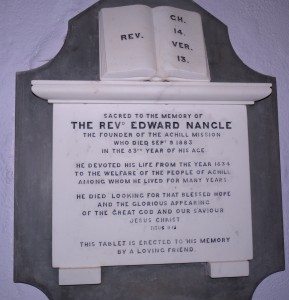

Several weeks after Edward Nangle’s death, a memorial committee chaired by William Johnston gathered in 17 Upper Sackville Street Dublin to raise funds ‘for the purpose of perpetuating in a suitable manner … the memory of the Rev Edward Nangle of Achill and Screen’.[14] The Honorary Secretaries were Rev Henry Seddall, Nangle’s biographer, and Rev Isaac Coulter, Knockbride Rectory, Baileborough, Co Cavan. Contributions were invited from ‘all friends of Protestantism and of Missionary Enterprise’. This campaign would lead to the erection of a memorial stone at St Thomas’ Church, Dugort, where Nangle had preached the consecration ceremony in 1855.

Today, the remains of Eliza Nangle and five of the Nangle offspring rest on the slopes of Slievemore just yards from the surviving Achill Mission settlement buildings. In the valley below stands St Thomas’ church where a portrait of the silver-haired Nangle looks down on Sunday worshippers and Achill Island visitors. Interspersed among the weathered headstones in the adjacent church cemetery are plain wooden crosses placed there in recent years by a joint effort of the local Catholic and Protestant communities.[15]

Some 190 unmarked graves have been identified in Achill cemeteries and marked with simple crosses. Many of these enfold the bones of Achill Catholics who became Church of Ireland members in the famine years – the crosses a powerful symbol of healing in the place where Edward Nangle toiled and preached in a different time.

REFERENCES

[1]Henry Seddall, Edward Nangle, The Apostle of Achill – A Memoir and A History (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co., 1884)349.

[2] Mr & Mrs S C Hall wrote of hearing ‘very opposite accounts’ of the Achill Mission when they visited the island in 1842. For an assessment of Nangle’s legacy see Niall R Branach, ‘Edward Nangle & the Achill Island Mission’ in History Ireland, Autumn 2000, and Patrick Comerford, ‘Edward Nangle (1800-1883): The Achill Missionary in a New Light’

[3] Achill Herald, July 1837.

[4] Achill Herald, October 1864.

[5] Achill Herald, July 1837.

[6] For an overview of the Achill Mission see Mealla Ní Ghiobúin, Dugort, Achill Island – The Rise and Fall of a Missionary Community (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2001).

[7] The Register of Baptisms, Marriages & Deaths for St Thomas’ Church, Dugort, Achill, lists the names of those who read recantations on conversion to the protestant faith in the years 1844-1846.

[8] Irish Church Advocate, 1 December 1880.

[9] Irish Church Advocate, 1 March and 1 April 1879.

[10] Irish Church Advocate, 1 July 1880.

[11] The Church Advocate, 1 October 1883.

[12] Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette, 15 September 1883.

[13] Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette, 22 November 1884.

[14] The Irish Times, 3 November 1883.

[15] For an account of the 2011 healing ceremony see The Mayo News, 27 September 2011.